Guest post by Nils-Christian Bormann.

Political instability has gripped Algeria, Cameroon, and Sudan in recent weeks and months. At best, protests remain peaceful and low-intensity violence can be resolved. At worst, these events may foreshadow the first steps towards civil war. These cases remind us that policy-makers face the urgent question of how to prevent the outbreak and escalation of civil violence.

Conflict researchers have identified the central causes of intrastate conflict such as state weakness, poverty, and horizontal inequalities between groups along political and economic lines. While these insights help identify states and regions at risk of civil war, they do not necessarily help prevent it. To do so, a better understanding of how to mitigate or even eradicate its root causes is needed.

Development economists in particular have taken on this challenge. A now thriving research program on poverty alleviation is tackling the economic motivations for armed conflict. Using field experiments to evaluate a range of different policy interventions in both largely non-violent and post-conflict contexts has shown promising results.

More recent work on building state capacity has revealed mixed evidence. Whereas some scholars find that specific education programs and contact with UN peacekeepers can promote order in weak states, others highlight how former combatants abuse rule-of-law institutions for their own benefit.

Conflict researchers know least about the alleviation of horizontal inequalities. If anything, scholars highlight the long-term persistence of group-based economic inequalities and the closely connected racism that date back to political developments hundreds of years in the past.

With regards to political inequalities, various forms of power sharing promise to prevent and resolve civil war, in particular when accompanied by third-party guarantees. The key question then becomes under what conditions political elites share power.

My own research demonstrates that elites in ethnically divided societies form coalitions to ensure their own survival in office. Specifically, they share power with leaders of other ethnic groups in oversized coalitions when support from their co-ethnics is uncertain due to shifting allegiances along cross-cutting cleavages.

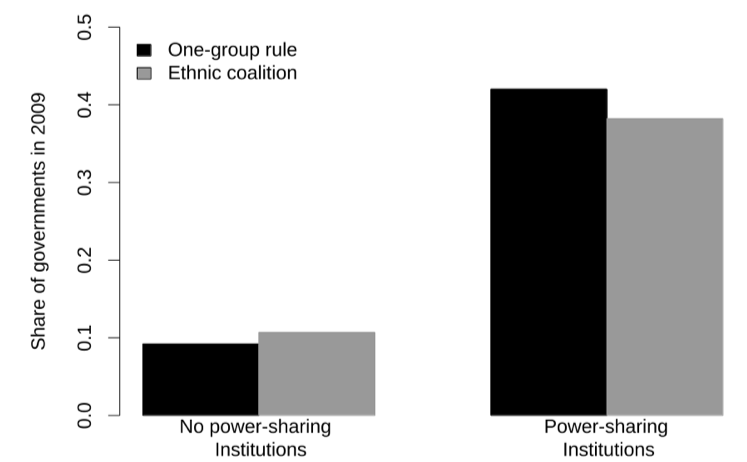

In contrast, formal power-sharing institutions that have long been considered to bring about ethnic cooperation, such as proportional electoral rules and democratic rather than autocratic regime type, seem to have little impact on actual power-sharing coalitions (as Figure 1 shows).

In a cross-section of ethnically divided states in 2009, multi-ethnic executive coalitions are as frequent in states with power-sharing institutions as in those without. Moreover, about 10% of all ethnically divided states feature ethnic power-sharing without power-sharing institutions that encourage it. These results persist throughout different years, in more complex regression models, and when investigating the effects of individual institutional arrangements.

The findings are consistent with research that locates the origins of ethnic recognition regimes as well as its potential for conflict resolution in the size of ethnic groups. Political leaders of plurality groups benefit from recognizing ethnic differences through increased support from their own group and by reducing mistrust among ethnic minority members. In contrast, state leaders with a minority background tend to avoid highlighting ethnic differences.

The different starting conditions for power sharing or ethnic recognition regimes have implications for the risk of civil war. A first insight of recent studies is that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for divided societies. Exploring the conditions for successful conflict prevention requires paying careful attention to domestic distributions of power and other contextual factors that affect the adoption and working of power sharing arrangements.

Next to seeking a deeper understanding of the conditions for successful power sharing, conflict researchers should collect more behavioral evidence on the conditions under which members from different ethnic groups cooperate.

Nils-Christian Bormann is a lecturer in the Department of Politics at the University of Exeter.