By guest contributors Austin Doctor and Stephen Bagwell

The weeks leading up to Cameroon’s February 2020 parliamentary and municipal elections were marked by severe violence. The leader of a prominent militant group, the Ambazonia Governing Council, threatened in December that anyone who sought to participate in or promote the elections would face consequences. In the following weeks, separatist forces fulfilled these threats by killing civilians, destroying homes, and burning election offices. Cameroon’s state forces acted in kind.

Around the world, state and non-state actors threaten and use violence in order to influence the outcomes of elections. Some of the most common forms of electoral violence include the use of coercive force against state agents, political parties, or voters themselves, as well as attacks against visible manifestations of elections, such as polling locations.

These tactics can be effective means of influencing election outcomes. Electoral violence can improve vote share for candidates who use violence, for example. (Interestingly, electoral violence may not discourage voter turnout.) Beyond its immediate effects, electoral violence also carries downstream consequences. For example, it can affect political attitudes, including satisfaction with democracy, social trust, and inter-ethnic cleavages.

Overall, existing scholarship has largely emphasized the social and political consequences of electoral violence, but what about its economic effects? This question is important. Electoral violence is hardly unique to Cameroon. Recent cases, such as those in the United States, Afghanistan, Côte d’Ivoire, and India, demonstrate that election-related violence is relatively common. Some estimates suggest that, since 1990, over 20 percent of national elections have been characterized by violence.

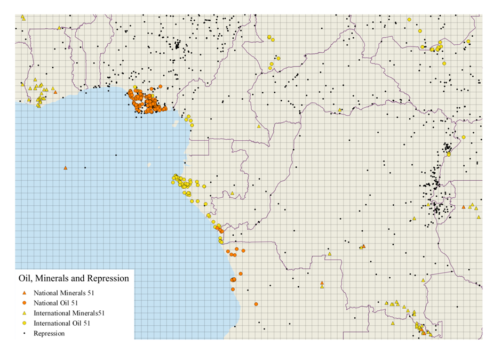

In a recent publication, we investigate the economic consequences of electoral violence in sub-Saharan Africa. Using data on the foreign direct investments (FDI) of 77 multinational corporations across 25 sub-Saharan African countries, we estimate the effect of electoral violence on the likelihood that multinational corporations divest their assets in a given country. The findings are stark: episodes of electoral violence nearly double the probability of foreign divestment.

Divestment—the sale of international subsidiaries, closure of foreign plants, and exit from foreign markets—is rare and expensive. Generally, firms are loath to lose profits by engaging in the costly and challenging act of relocating their assets. As such, divestment is most likely to occur when firms are struck with an especially severe sense of risk. This is exactly what electoral violence brings: more than other forms of violence, it credibly signals the likelihood of both immediate and sustained changes in the business environment, including policy change, disruptions in production, and escalation of conflict. All of which are bad for business.

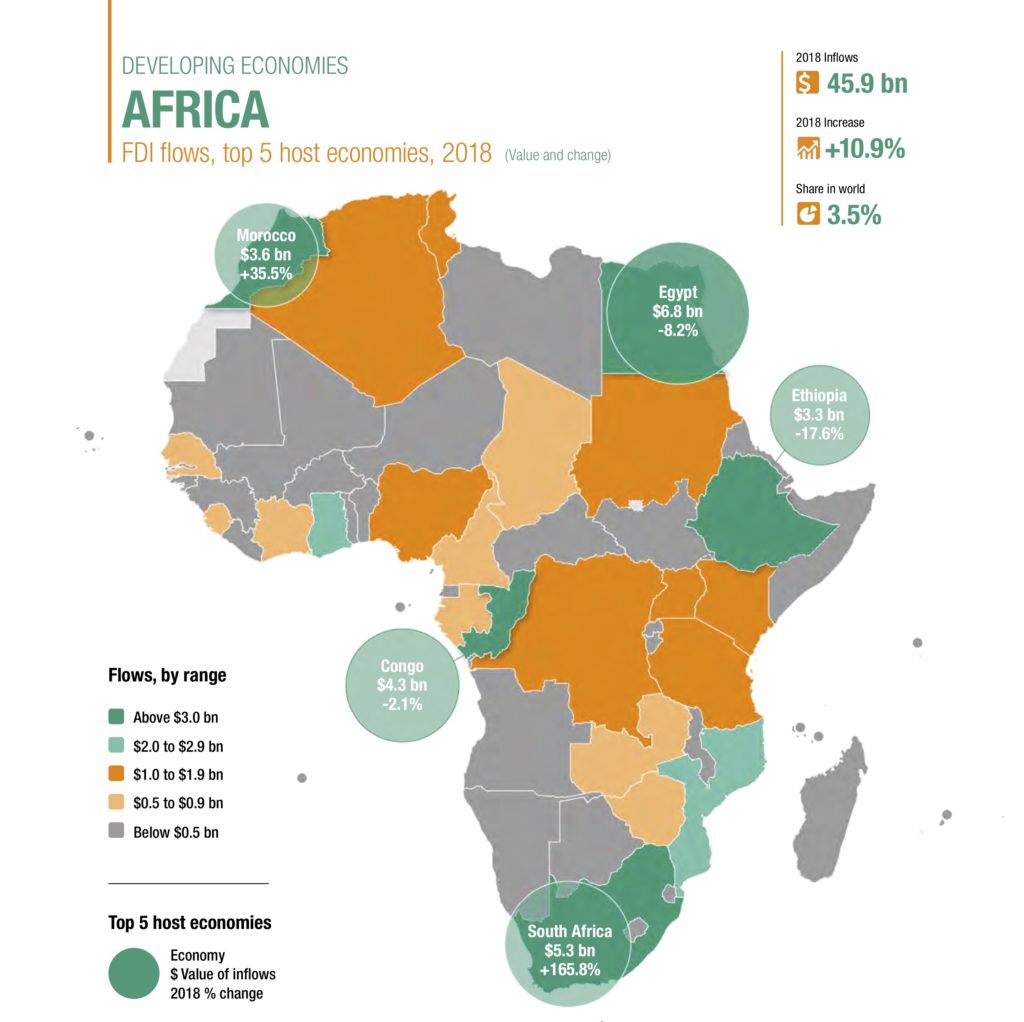

Many emerging economies, including many in sub-Saharan Africa, depend on outside investment. According to the most recent UNCTAD World Investment Report, a significant number of economies in the region receive high levels of foreign investment (it does not account for development loans from China or other states). FDI stocks (the cumulative total of FDI for a given time) in African countries averaged 38.6 percent of their GDP. And despite decreases in investment globally, foreign direct investment is on the rise in Africa. FDI flows to African countries rose by 11 percent to $46 billion in 2018. The subsequent revenues promise an opportunity for economic growth and development in the region. Electoral violence threatens to undermine these gains.

The effects of electoral violence on divestment are comparable in size to those of civil war and terrorism, and are more consistent. From firms’ perspective, electoral violence is not militancy’s little brother: episodes of electoral violence send especially strong signals to foreign firms about political stability in a country.

This is a big year for national elections in sub-Saharan Africa: 20 African countries will host presidential or legislative elections in 2020. This count does not include municipal elections such as those scheduled to occur in Angola this year. Some of the upcoming elections are at a higher risk of violence than others. For example, the Electoral Violence Intelligence System forecast Mali at a 74 percent risk of experiencing election-related violence in March. The risk in Guinea, which finally held its habitually delayed parliamentary elections, was forecast at 43 percent in the same month. The elections in both countries were characterized by violence. A second round of elections is scheduled in Mali for 19 April.

A rise in election-related violence will have dire consequences for countries, but it may also disrupt/hamper global partnerships in the region. In December 2018, the Trump administration released the New Africa Strategy: Expanding Economic and Security Ties on the Basis of Mutual Respect, in which the US government lists the “advancement of commercial ties and US investment” as a key instrument both for furthering its own interests in Africa and facilitating economic stability in the face of a growing militancy in key regions of Africa, such as the Great Lakes region and the Sahel. Advancement of this and other economic strategies for the region may slow with a rise in electoral violence.

Some questions remain unanswered. We don’t know the impact of electoral violence on other economic factors such as sovereign credit ratings, unemployment rates, foreign aid, or economic production. But it is clear that using violence, to intimidate the opposition or bolster supporters, is an effective way to gain and maintain power. And yet once those short-term gains are secured, an analysis of the economic consequences of electoral violence shows that these tactics may impose severe financial costs that will be borne by the nation as a whole.

The repercussions of electoral violence are economic as much as they are political, and their impacts ricochet out. Local and international efforts to preempt or reduce election-related violence are important in their own right. They may also provide additional benefits by maintaining stability in economies—and communities—that would face severe distress from disruptions to foreign investment.

Austin Doctor is an assistant professor of government at Eastern Kentucky University. You can follow him on Twitter @austincdoctor. Stephen Bagwell is an incoming assistant professor of political science at the University of Missouri in St. Louis. You can follow him on Twitter @StephenMBagwell.