As President Obama contemplates his next move on Syria, he would do well to consider the cautionary tale of the late British Prime Minister Anthony Eden, whose disastrous handling of the 1956 Suez Crisis led to his commemoration as “the last Prime Minister to believe Britain was a world power and the first to confront a crisis proving she was not.” Evidence of the US’ eroding influence in the Middle East should prompt deep consideration on the consequences of unilateral action that produces little more than ambiguous results. Recalling 1956, the American failure to recognize the limits of its own waning influence and the rise of regional aspirants’ will define the balance of power in this fragile region for the generation to come. However, unlike in 1956 there are no obvious rising superpowers to step in and pull today’s dangerous array of regional aspirants back from the brink.

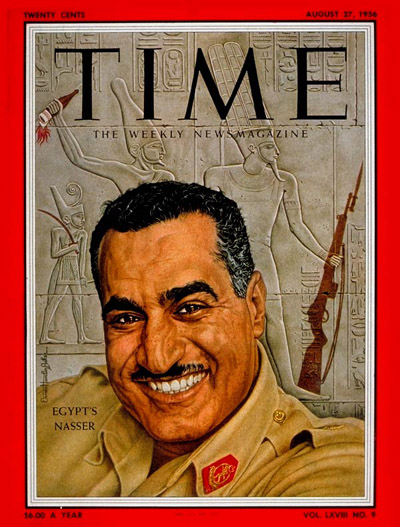

The parallels between the current crisis over the Assad regime’s alleged use of chemical weapons and the 1956 crisis sparked by the nationalization of the Suez canal are not immediately apparent. But as with Great Britain’s dilemma over how to respond to that “upstart dictator,” today the United States is suddenly faced with the recognition that changes in the regional chess board have already revealed the limits of US power.

One has to remember that Nasser would have never have been so audacious as to unilaterally nationalize the Suez canal had he not been certain Britain lacked the wherewithal to overrule him — much like Bashar al Assad’s use of chemical weapons today.

Nasser knew that Britain’s era of dominion in the region was through. He saw Britain’s ignominious withdrawal from Palestine and understood that the British public had no stomach for lengthy entanglements in foreign sectarian conflicts. Nasser was also aware that regional powers, such as himself, were gaining influence and could prod weaker actors into taking steps at odds with Great Power interests. Just months before the Suez Crisis King Hussein of Jordan, considered the most dependable British ally in the Middle East, politely declined to join the British-orchestrated Baghdad pact and sent his own cadre of British military advisors packing. King Hussein, of course, had just seen the British sit by while the Free Officers — in an early example of the Egyptian military facilitating the people’s will — swept away their ally King Farouk.

Reading the writing on the wall, Nasser took measures he believed necessary to secure his own position in the rapidly changing regional landscape. Whether or not he anticipated the now infamous 1956 collusion between Britain, France and Israel, Nasser was certain he would prevail. After the Suez Crisis the Middle East lurched into a turmoil lasting until Kissinger negotiated the Egyptian-Israeli and Syrian-Israeli disengagement agreements in 1974. This Cold War-imposed stability held until the 1991 Gulf War signaled the beginning of US global, and by extension regional, hegemony. Yet that “pax Americana” has been unraveling since the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

This is where the parallels between the 1956 story of imperial hubris and the current crisis diverge, and new dangers come into focus. Unlike in 1956, it is unclear who the next regional hegemon will be, and there is no comforting Cold War balance of power to impose stability and contain violence. Russian influence is testing the waters through the standoff in Syria. Iran is as well, but so is Saudi Arabia and tiny Qatar – who may be little more than “300 people and a TV station,” but has certainly managed to funnel enough arms into the hands of the Syrian rebels to prevent Assad from achieving decisive victory.

And there is Israel to consider – the unquestioned leading regional military power whose willingness to launch armed attacks wherever and whenever it deems fit doesn’t look like self-defense to those in the region.

If the US launches strikes against Assad, and does nothing more, Assad will be strengthened, as will Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Iran. Israel, of course, will be unimpressed with this situation and continue to rely on its own measures. While Russian influence will increase in this newly-competitive arena, will it be enough to restore a semblance of calm?

This brings me to the final lesson from 1956. Among the many prescient decisions Eisenhower made during the crisis, the most overlooked was his choice to work through the UN. Eisenhower knew the nascent international organization was in trouble, and if the crisis was resolved by the world powers acting alone it would be doomed. Instead, Eisenhower purposefully worked through diplomatic channels and endorsed the settlement orchestrated by UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold — which produced the first UN peacekeeping force — a victory for diplomacy that gave the organization sufficient credibility to carry on, a gesture in favor of multilateralism repeated by George H.W. Bush in 1991.

Today it appears that Obama is willing to pull the last leg from that shaky stool, as well.

2 comments

Except that this ignores the serious differences. The UK, France and Israel were forced to pull out because both the US and Soviet Union made it clear that they were willing to take steps to force those nations to pull out.

Then there’s the fact that China and Russia made it very clear with their vetoes that they are not at all interested in doing anything that might be problematic for Assad. And good luck finding peacekeepers for Syria, presently the only nation that actually wants to send any is Russia and the reasons for that are self evident.

Lastly, this ignores that 1991 was an interstate war, not a civil one (and the Soviet Union was still furious with the US about it). It’s far easier politically and militarily for the US to be involved in the former than the latter.

In other words, there may be some useful information from this on the possible unintended consequences of strikes on Syria including the possibility of the US accidentally strengthening Assad’s domestic position, but let’s not force comparisons that simply don’t work. We see enough of that with people writing on Iraq and South Vietnam.