Guest post by Ore Koren.

Does food security increase the frequency of civilian killings in some developing countries? Or can it make such atrocities less likely? The answer to these questions depends on how troops and civilians view the prospects of long-term cooperation, and the strategies they employ.

Current theories on violence during civil war frequently associate it with previous enmities and discriminate violence. Yet, even within countries that are experiencing civil war, violence varies over space and time. Some villages might suffer many civilian killings by armed troops while others do not. These villages might go through years of relative peace followed by years of intense violence. New research shows that, in the developing world, food availability and farmland density can help explain violence against civilians.

Throughout history, living off the land was a regular characteristic of warfare. Although logistic supply chains significantly reduced the need of modern militaries to rely on local populations for support, economic capabilities required to maintain such systems limit the vast majority of armed groups in the developing world from enjoying regular support. This deficiency forces many armed actors to routinely live off the land in times of war and peace. Not only rebels and militias are forced to do so, but also official military forces, for instance in Uganda and Zaire.

In many cases, however, troops have no reason to “kill the goose that lays golden eggs”: if civilians produce food and willingly support the troops, then no violence is needed to guarantee these provisions. In these situations, abundance of food resources can produce a pacifying effect, as both troops and civilians enjoy ample access to sustenance and interact peacefully. Because they believe these interactions are likely to continue, both sides prefer to cooperate, and there is little need for violence.

In the Mizoram and Naga states in India, for instance, rebels are highly embedded in the local population. Both rebels and pro-government forces prefer to cooperate with the locals and appeal to their “hearts and minds.” The National Resistance Army (NRA) in Uganda and Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front in Ethiopia are similar examples of such peaceful cooperation resulting from long-term interaction.

In other cases, however, violence is used to secure food resources. For instance, the NRA in Uganda, which during peaceful times preferred a strategy of cooperation, turned to violence to extract food resources for poorly fed soldiers when conflict with the government intensified.

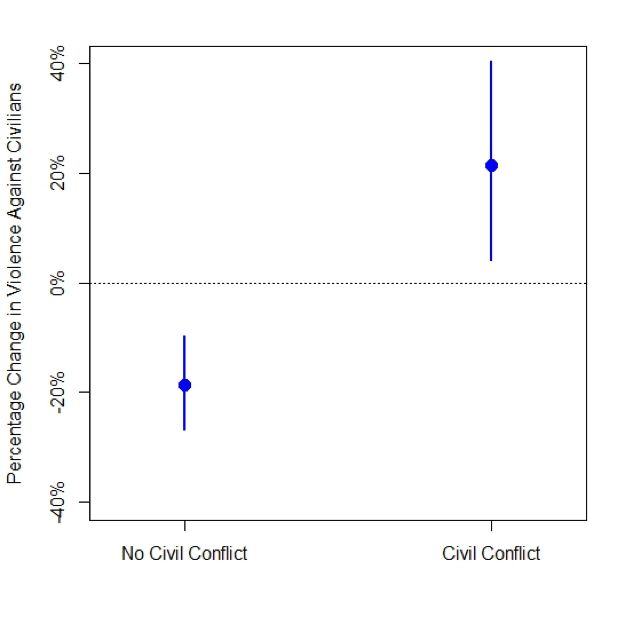

For a food security-based theory to help us understand violence against civilians, it must explain not only why armed actors might decide to target some areas for food access, but also when violence is favored over co-optation. As Benjamin Bagozzi and I show in a recently published article on food security-related atrocities against civilians in Africa, the existence of immediate conflict in agricultural regions leads armed actors to discount the benefits of future interactions in favor of obtaining food immediately through violence and intimidation. Our research shows that higher densities of cropland indicate increased frequency of violence against civilians during periods of conflict, but have a pacifying effect during times of peace (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1

Importantly, the likelihood of violence is influenced by decisions made not only by armed troops, but also local civilians. In relatively peaceful time, civilians who live off their croplands have fewer incentives to resist armed actors’ food demands. In many cases, they might view these troops as potential long-term partners, and be allowed to choose the amount of food support they provide in return for more political participation.

If conflict intensifies, however, the civilians – like their armed counterparts – have much less reason to cooperate. Civil war devastates the region, straining food availability and reducing food reserves. Territories frequently change hands, which means that the old occupier will not be able to credibly punish civilians who refuse to give away their meager food rations, while the new occupier might be more likely to punish those who collaborate with the enemy.

This has important implications for our understanding of violence in ongoing conflicts, such as the civil war in Syria or Iraq. Agriculture is an important source of income for the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq (ISIS), which currently rules over large parts of the breadbaskets of the two countries. The group maintains agricultural production in these regions despite the ongoing conflict. ISIS is notorious for its violence against noncombatants, much of which takes place in these regions. Although far from the only explanation for the group’s brutality, our research sheds light on some of the causes of violence against civilians in these agricultural areas.

Inherently, the relationship between food security and violence is related to the notion of externalities, or the unintended consequence of war. Conflict produces a shift in dynamics, as troops must secure food resources from reluctant civilians. For policymakers, this illuminates some new directions for peace-building efforts and preventing violence renewal.

For example, improving food distribution within conflict-prone zones can help ameliorate violence against civilians by reducing negative externalities. This research can also help to identify those locales within a given country in which UN forces or other external parties might intervene and most effectively prevent violence against civilians during ongoing conflict: namely, in food abundant, agricultural areas.

Ore Koren is a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Minnesota and a Jennings Randolph Fellow at the United States Institute of Peace.