By Bert Suykens and Julian Kuttig

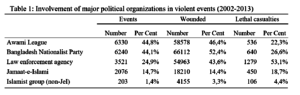

The 2016 attack in the heart of Dhaka’s diplomatic zone Holey Artisan Bakery, left 22 dead, including 17 foreigners. It was the culmination of a series of lethal attacks by Islamist radicals against atheist bloggers, LBGT-activists, Hindus, Buddhists and foreigners that started in 2013. While these attacks captured international media headlines, our data shows that a (policy) focus on radical Islamism, would fail to recognize the more important interlinkages between democratic party-politics and violence. Our data suggests that between 2002 and 2013, over 14,000 instances of political violence took place in the country, of which only around 16 per cent involved Islamists (see table 1).

The scale of political violence is puzzling because up until the elections of 2014–which the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) boycotted–ethnically homogeneous Bangladesh had a fairly stable democratic system. Although relations between and within political parties were tense, the anti-incumbency vote had ensured a turnover of power since 1991, including competitive local elections. Furthermore, Bangladesh has made solid progress, not only in terms of robust economic growth, having now reached middle income status, but also in terms of human development.

What explains this puzzle? As our research shows, while Bangladesh has been a functioning democracy, many are willing to commit violence to gain access to state patronage, where state resources are used to attract and reward supporters and activists. As the state is firmly under the control of the democratically elected ruling party, gaining access to the party’s many wings offers a clear-cut access to jobs and resources, certainly given the limited opportunities elsewhere.

Violence plays a key role in brokering this access. Inter-party violence is used by party activists to show their commitment to the party, while intra-party violence can secure a particular faction’s position. These dynamics are particularly visible on public university campuses, one of the most violent arenas.

First, the incumbent’ student group is expected to fully control these campuses, often not allowing opposition activists to be present on campus. Second, student leaders of the ruling party use violence to capture territory on campus, often against other factions of the same party. Student dormitories (halls) play a particularly important role as they serve as important recruitment grounds and access to state resources.

Control over these halls is maintained often against the violent resistance of other factions. Such violent control signals violence capacities and assertiveness and is performed with the expectation to be awarded a position, either within the student organization, or after as an elected representative or in state bureaucracies, most specifically the police. These positions are considered the gateway to middle class lifestyles. As a result, the operation of everyday and highly factional party-politics in Bangladesh has been one of the main drivers of political violence in the country.

Moreover, criminal (mastan) activities, such as extortion, land grabbing, smuggling or drug trafficking, have become a major source of income for party leaders. Some commentators have therefore called the political system in Bangladesh a mastanocracy. Resulting violence goes well beyond political contestation, but is difficult to distinguish, deriving from the patronage-based entanglement of party-politics and crime.

Counterfactually, events of political violence plummeted to its lowest point during a two-year extra-constitutional military-backed caretaker government (2007-2008) that assumed power as a reaction to widespread violence and political rioting in the wake of the national elections in 2006. During its two-year autocratic tenure, the caretaker government suppressed most party-political activities to restore stability and attempted to crack down on corruption before restoring democratic government and holding elections in December 2008. Besides low levels of political violence, there is a widespread perception that in those two years politically backed criminal activities like extortion or land grabbing declined significantly. This does not mean that an autocratic military regime should be considered as the solution, but rather points towards the role of power struggles and violence within the realm of what we call democracy.

The lethality of the everyday power struggles discussed here is surprisingly high. Our data suggest that over 126,000 people were wounded and over 2,400 killed between 2002 and 2013. Election years tend to be excessively violent, with our full 1991-2014 data showing clear peaks in violence in 1996, 2001, 2006 and 2013 (in the run-up to the January 2014 elections), with post-electoral slumps in violence. As table 1 shows, the two main political parties (Awami League and Bangladesh Nationalist Party) have been at the forefront of such political violence, not Islamists as the media often depicts.

Table 1: Involvement of major political organizations in violent events (2002-2013)

Notwithstanding their prominence in international reporting on Bangladesh, such Islamist groups tend to play a comparatively minor role. There has been a tendency to compound various incidents and groups under the umbrella term Islamist extremism, but Islamists’ engagement in violence is mostly under the party-political banner of Jamaat-e-Islami (which was part of BNP-led governments of 1991-1996 and 2001-2006). The most prominent example was the large-scale violence during Jamaat-led 2013 protests–including a massive response from state security forces—following the conviction of a number of Jamaat’s leaders in ‘war crime tribunals’ and their subsequent execution. Several proscribed insurgent groups were active, but this did not lead to excessive casualties (see table 1).

There is little doubt, however, that the situation has deteriorated since 2013, hitherto culminating in the 2016 Holey Artisan Bakery attack. Still, more people died in the 2016 local elections (64) than in the combined attacks by Islamist groups against bloggers, Hindus, Buddhists and foreigners in the 3.5-year period between the killing of the first blogger in February 2013 and the attack on the Holey Artisan Bakery in July 2016 (48, my own tally).

With Bangladesh gearing up for general elections at the end of 2018, the coming months will prove crucial. Violence within democracies with relatively high economic and human development like Bangladesh pose major new challenges to policymakers. Being far removed from the fragile bottom billion, there is a need for the development of novel research and policy perspectives, that reevaluates the still pervasive perception of the so-called middle class as a main driver for the development of stable liberal democracies.

While international drives for the development of more quality employment in Bangladesh are warranted, there is a continued need to identify the underlying causes of violence. Doing so requires policy makers to escape simple explanations that are based on contentious divisions along religious, ethnic or ideological lines and focus more on the mundane, everyday life trajectories of members of violent prone-groups and their patronage networks in order to examine these arguably more complex cases. While efforts to introduce and promote non-violent forms of contention are appreciated, these cannot tackle the proliferation of internal violence which lies at the heart of democratic rule in Bangladesh.

Considering the complexity of these violent democracies and the relative silence on the side of academia and policy maker with regard to strategies to counter such developments, it is time to implement a new research agenda that attempts to first understand the dynamics of violence in democracies like Bangladesh and second develop recommendations and strategies for policy stakeholder.

Bert Suykens is Assistant Professor at the Dept. of Conflict and Development Studies, Ghent university and specializes on field work-based analysis of conflict and political violence in Bangladesh and India. Julian Kuttig is a PhD student at the Dept. of Conflict and Development Studies. His fieldwork tries to understand the linkages between violence and a local political order in Rajshahi, Bangladesh. This blog piece is part of a series of short publications by Ghent University’s Conflict Research Group and Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit to situate and explore the topic of ‘violent democracies’ in relation to middle-income countries.