By Omar García-Ponce, Lauren Young, and Thomas Zeitzoff.

This past July, Mexicans voted for change. Leftist leader Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) was elected president in a landslide victory, and his MORENA-led coalition won a comfortable majority in congress and several local elections. Security policy was one of the top issues in the campaign. Since December 2006—when former president Felipe Calderón launched Mexico’s “War on Drugs”—more than 270,000 Mexicans have been killed and at least 40,000 disappeared. AMLO campaigned on a promise to shift away from the militarized strategy adopted by his predecessors and to focus on violence prevention. These preventative policies even included decriminalization of marijuana and amnesty for low-level offenders. Yet in the months since taking office, AMLO has placed the creation of a 60,000-member National Guard at the center of his security policy, which critics see as the continuation of the failed policy of militarization.

López Obrador has reiterated that the National Guard will be under civilian control and that his broader security strategy includes a number of social programs to address the root causes of crime. However, it is a concern that the core of his strategy points towards formalizing the militarization of public security, neglecting the need for police reform and putting human rights at risk. Is AMLO’s security policy likely to reduce the record-high levels of violence in Mexico today and improve the rule of law?

When AMLO announced in 2016 that he was considering amnesty as a policy to reduce violence, he was attacked for ‘promising impunity’ for ‘the unforgivable’. Militarizing law enforcement however has widespread support, with recent polls showing that 64% support the creation of the National Guard. Polls in Mexico have consistently shown high trust and support for the military, despite widespread public knowledge of the military’s role in atrocities and human rights abuses. Citizens seem to want immediate and visible punishments for criminals. For instance many Mexican citizens complain that due process protections create a revolving door that lets accused criminals out of prison as soon as they are arrested.

But even if punitive policies poll well, they are unlikely to reduce violence over the longer term. Research that we have been conducting in Western Mexico over the past two years on exposure to violence and attitudes towards criminal justice policy sheds some light on how citizens make this tradeoff between preventing future crimes and a desire to see criminals punished.

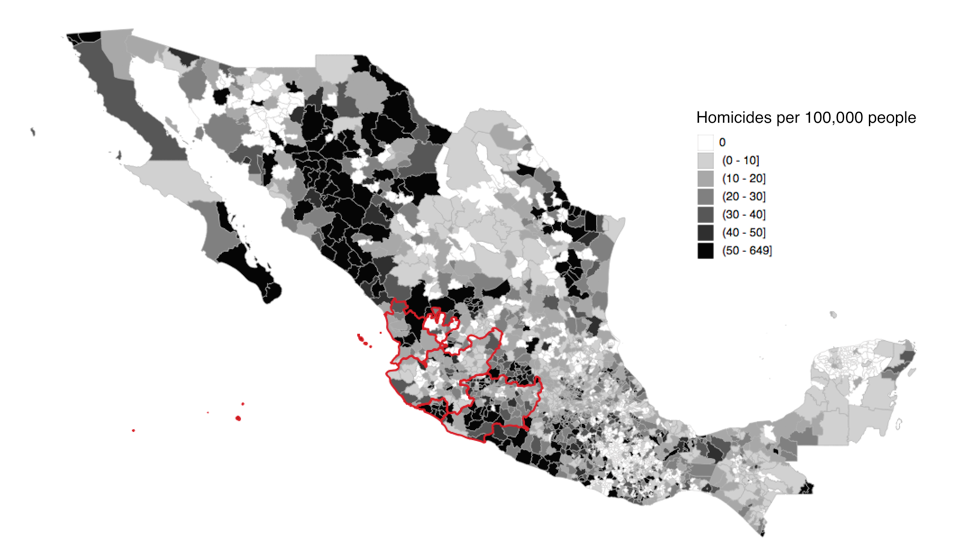

Why do people support punitive justice policies? Our hunch was that citizens have multiple priorities when deciding how they want crime to be punished. They care about preventing future violence, but also value punishing criminals for the harm that they’ve done. And anger in the wake of outrageous forms of violence can cause citizens to place more value on making sure that criminals get punished, even at the cost of preventing future crime and the legality of the process. We ran a series of studies with a representative survey of 1,200 respondents in the western states of Colima, Jalisco, Michoacán, and Nayarit in 2017 to understand citizens’ preferences about criminal justice.

Figure 1. Map of Western Mexico (survey regions in red)

Our first study shows that individuals who have been victimized are on average angrier, and more supportive of harsh punishments such as bringing back the death penalty. In our second study, we presented respondents with three hypothetical criminal scenarios, and randomly varied whether there was additional information that made the crime morally outrageous such as the abuse of children or desecration of a body. We find that morally outrageous crimes lead respondents to support harsher punishments, and to care less about whether the punishments are legal. Finally, we use another set of 125 crime vignettes to show that victims who are perceived to be “innocent” are most likely to trigger this anger and demand for harsher punishment, whereas the severity of a crime is less important.

The most important finding in our study is that not all crimes are equal in triggering the harsh justice response. The perceived innocence of a victim matters more than the severity of the crime. A grandmother who is the victim of an assault will generate more outrage than a narco being killed. Across all three studies, it is only violence against civilians that triggers outrage and a thirst for retribution. Municipal homicides, for example, in which victims are often affiliated with organized crime groups, do not affect citizen anger and support for harsh punishments. People may be willing to tolerate (or ignore) high levels of extreme violence—such as beheadings and torture videos—as long as the violence is perceived as a self-contained war between criminal organizations. In contrast, crimes against innocents such as extortion of local businesses, kidnappings of everyday citizens, and the murder of student activists trigger anger, outrage, and a desire for punishment.

These findings have two implications for AMLO’s administration as they figure out how to tackle the enormous challenge of violence and impunity in Mexico. First, our research suggests that the primary goal of any security policy should be to protect civilians from less spectacular but extremely prevalent, demeaning, and frightening forms of everyday abuse such as extortion, robberies, and physical assault, among others. Reducing levels of victimization should reduce the high levels of support for punitive policies. By contrast, if policy is designed to mete out punishment for its own sake, it could set off an even greater cycle of retribution and insecurity.

Both of AMLO’s predecessors deployed the Mexican military and the federal police to ‘do something’ about organized crime. Yet the militarized mano dura policies they both pursued have made the violence worse and increased violence against civilians. And ultimately, public opinion turned against the incumbents after civilian victimization continued. Our research helps explain why ‘tough on crime’ and ‘mano dura’ policies may be popular under some circumstances, but may not be a good way for a politician to stay popular: they channel citizen anger over crime into harsh punishments, but these punishments are not effective policies to reduce violence.

Omar García-Ponce is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at UC Davis. Lauren Young is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at UC Davis. Thomas Zeitzoff is an Associate Professor in the School of Public Affairs at American University and is a regular contributor at PV@Glance.

1 comment

Interesting study and results. Would not have expected more violence as well as violence against civilians.

Looking forward to more of your insights and studies.