This post is part of the “Would Someone Please Explain This to Me?” series.

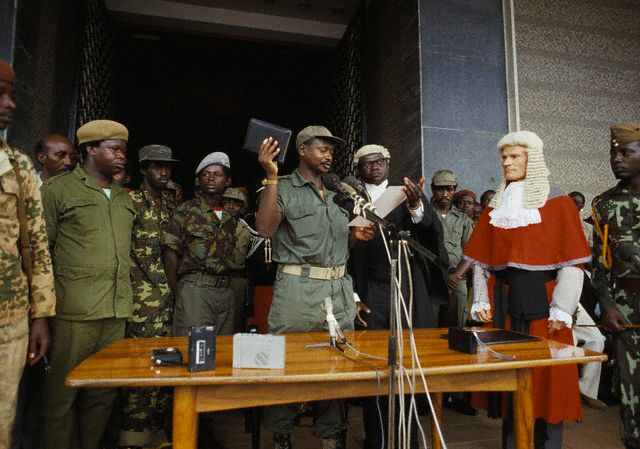

Reader TJW asks: “Why have so many of Africa’s great revolutionaries – Meles, Museveni, Kagame, Mugabe, Afwerki – failed to give-up power once they gained it? Is this because leaders of rebel movements are hard-wired into authoritarian command-and-control types of politics even when out of the bush and in control of the state? Perhaps they come to associate national development, progress and stability with their own individual leadership? Or do plenty of revolutionaries become democrats?”

A common refrain in newspaper accounts on Africa is that that Africa’s lack of democracy and economic development is due to the poor quality of its leaders. If only Uganda, or Zimbabwe, or the Democratic Republic of Congo produced more Nelson Mandelas – more principled, less corrupt leaders – then poverty and violence would decline.

On the surface, this explanation appears to mirror what we see. Mugabe started as a rebel fighting for democratic ideals only to become one of the continent’s worst dictators. Perhaps there is something uniquely “bad” about Africa’s leaders – something that makes even the most revered freedom fighters corrupt and greedy once in office.

This explanation, however, ignores two structural features that are driving this bad behavior in many of Africa’s countries: rich resources and weak political institutions. Countries like Uganda and the DRC hold substantial resources that tempt leaders to line their pockets and use the money to easily buy off opponents. These countries also have few institutional restraints on their executives, making it easy for leaders to behave as they will. Most revolutionaries, when put in this structural situation, would likely behave the same way.

The revolutionaries who do become democrats, such as the IRA in Ireland, are the ones who already operate in a highly institutionalized environment where executive power is checked. In unrestrained environments where wealth is there for the taking and one’s time in office is uncertain, the incentives to plunder are often too strong to resist.

6 comments

Exactly. Institutions matter.

Just as the principle of non-violence. Even in the absence of institutional checks on power, there could be other checks. Like thousands of people occupying the streets. But a violent overthrow of any existing despot will effectively scare all those people off the street, and hence remove that potential check on power.

If the overthrow is non-violent, on the other hand, the people will already be in the streets, hence the check will already be there. Which is why I predict the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt to be rather successful, while the revolutions in Libya and Syria will look a lot more like those mentioned in the article.

Uganda had a new constitution which was established probably through the most elaborate consultation process from the villages, and was then heralded as a new beginning. And as for the resource curse argument, its is an oversimplification; Which resources does Rwanda have? Uganda’s hydrocarbon deposits were discovered few years ago long before Museveni was in power. As such it offers little insight why these folks over stay in power.