Guest post by Cullen Hendrix

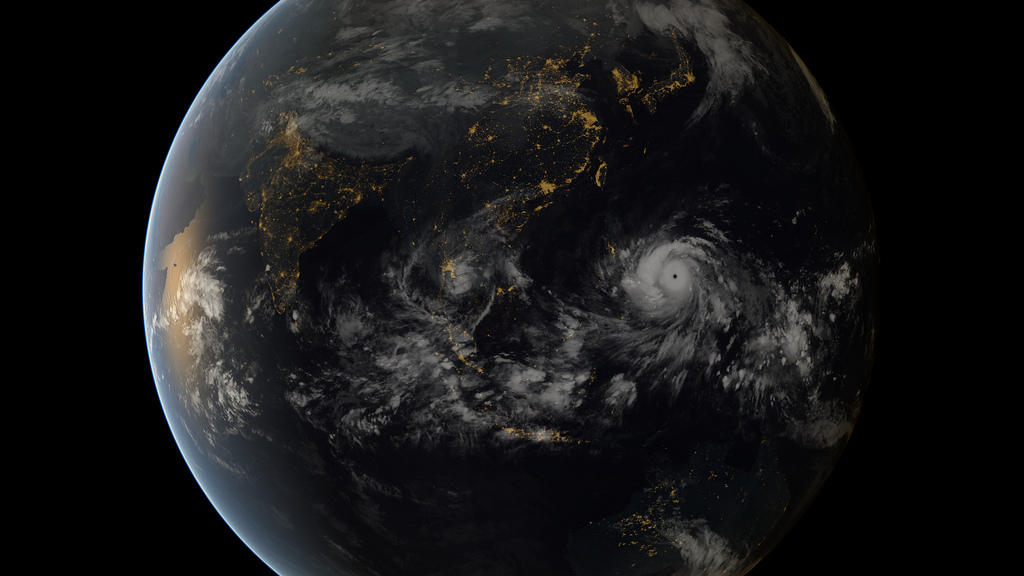

Do natural disasters, like Typhoon Hayian, fuel rebellion and social unrest? Given the Philippines’ long history of armed insurrections, there is growing concern that the storm will lead to large-scale violence. Many communities have yet to see emergency relief, and desperation has led to anger, looting and several deaths. Eight people were crushed by a throng of looters at a government food warehouse in Alangalang, and gunfire between armed men and government forces reportedly stopped a mass burial in the hard-hit city of Tacloban. While there will likely be significant political fallout from Typhoon Hayian, it is more likely take the form of punishment at the polls and demonstrations in the streets, rather than in civil war.

The literature has not reached a clear consensus but suggests that democratic countries like the Philippines are relatively safe from violence. Dawn Brancati and Philip Nel and Marjolein Righarts found strong evidence for increased likelihood of armed conflict following natural disasters. More recently, Rune Slettebak found that countries affected by climate-related natural disasters (storms, floods, and droughts) were less likely to experience armed conflict, and Drago Bergholt and Päivi Lujala found that while climate-related natural disasters cause economic contraction, they do not appear to affect the propensity for armed conflict. Looking specifically at earthquakes, Alastair Smith and Alejandro Quiroz Flores found that major protests were more prevalent after earthquakes, but did not relate these protests to armed conflicts. The balance of evidence suggests that while natural disasters fuel public demonstrations, they are not robustly linked to armed conflict.

Reasonable people do not hold the government responsible for earthquakes, typhoons, flash floods or other rapid onset natural disasters. Even insurance companies, for whom assigning blame is a key to guarding the bottom line, term such events “Acts of God,” for which no one can be held accountable. People do, however, hold governments accountable for their preparations for and responses to disasters. Incumbent governments know this, and their responses are typically geared toward shoring up political support among key constituencies. In functioning democracies, this tends to result in more effective post-disaster emergency response. Michael Bechtel and Jens Hainmueller found that effective emergency response to the 2002 Elbe River flood in Germany immediately increased incumbent vote shares in disaster-affected areas, and that the effect carried over to elections three years later. Andrew Reeves found that in the United States, “swing” states receive presidential disaster declarations – which can move billions of dollars – about twice as frequently as non-competitive states.

In non-democratic systems, disaster response policies generally cater to the more narrow interests of urbanites in important political and economic centers, with predictably disastrous consequences for more economically and political marginalized populations. Cyclone Nargis killed at least 138,000 people in Myanmar’s Irrawaddy delta in 2008, with catastrophic effects for minority ethnic Karens. Moreover, the military government refused most international disaster aid, perhaps motivated by concerns that aid delivery would heighten international awareness of human rights conditions on the ground. These more targeted responses (or non-responses) to disasters make for bad humanitarian outcomes but good politics: Alastair Smith and Alejandro Quiroz Flores found that while democratic governments are often ousted from office following major earthquakes, the rate at which autocratic governments are deposed is not significantly different following similar disasters.

Disaster response can also expose the venality and corruption of the incumbent regime. Nicaragua’s Anastasio Somoza famously raided international disaster relief to the 1972 Managua earthquake, catalyzing middle-class and urban support for the opposition Sandanistas, which ultimately deposed Somoza in 1979. While commonly cited as an example of drought-induced rebellion, the early 1990s Berber-minority Tuareg uprising in Mali was fueled largely by grievances over embezzlement of international relief funds by government officials and military officers.

If grievances are so prevalent after natural disasters, why do they not lead to conflict more often? Even if people have the motive to fight, they also need the capability to do so, and the hardships imposed by natural disasters may limit such capability. Kyle Beardsley’s and Brian McQuinn’s study of the differential impacts of the 2004 Asian tsunami on conflict in Sri Lanka and Indonesia demonstrates this point nicely. The tsunami had disastrous effects for rebel-controlled territory: Aceh in the case of Indonesia, and Jaffna in the case of Sri Lanka. For Gerakan Aceh Merdeka (Free Aceh Movement), whose primary resource base was the local Acehnese population, the tsunami destroyed their resource base and forced them to the negotiating table. In contrast, the Liberation Tigers of Talim Eelam’s access to a large diaspora population allowed them to sustain their war aims. While poverty and marginal livelihoods can motivate participation in rebellion, hungry, desperate individuals without access to basic necessities do not make the most formidable fighters. The fact that food denial is often incorporated into counterinsurgency operations suggests that acute, severe scarcity should suppress insurgent activity and attacks.

Comingling democratic elections and relatively high levels of government corruption, the Philippines seems like a most-likely case for negative political fallout from the disaster. But the negative consequences are more likely to play out at the ballot box and in the streets, rather than via armed insurrection in the bush.

Cullen Hendrix is Assistant Professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver and Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. At Korbel, he directs the Environment, Food and Conflict (ENFOCO) Lab. His research models contentious politics – ranging from urban protest to armed conflict – as the outcome of interactions between domestic political institutions, global markets and advocacy networks, and environmental degradation and climatic change.

2 comments