In its ongoing assaults on rebel strongholds, since mid-December the Syrian military has been making frequent use of a weapon that is as puzzling as it is nasty: barrel bombs. These decidedly low tech, improvised weapons return little in military value: they are inaccurate, cumbersome and prone to explode early, too late or not at all. They are, however, very scary weapons, and do a good job of delivering a grisly, terrifying end to those with the misfortune of being under one shoved out of the back of a helicopter. And while they unquestionably reinforce the regime’s reputation for barbarity, as Secretary Kerry suggests, the timing and purpose this nasty weapon’s new prominence raises some interesting questions about the regime’s “grand strategy.”

First, the regime’s apparent reliance on what is essentially a homemade bomb comes at a time when the rebels appear to be losing ground to both in-fighting and regime assaults. Why make such prominent use of a weapon that suggests the regime could be running low on munitions? Conventional wisdom holds that this tactic is part of an effort to soften up Aleppo in advance of a major offensive. Again, while this objective is entirely plausible it doesn’t explain why the regime is demonstrating a preference for this tool over other types of devastating weapons such as cluster bombs or Russian-linked fuel-air bombs (which mix fuel with oxygen in the air, before igniting the cloud in a large explosion) such as the one reportedly used over the northern city of Raqqa.

Second, the regime is conducting this very well televised onslaught at the same time it is attending the UN-sponsored conference in Geneva and scoring points by negotiating a deal to allow civilians safe passage from the remaining rebel areas in Homs. Why pummel civilians in one rebel-held city and make arrangements for their safe passage from another? Again, it makes sense that evacuating civilians would be a reasonable precursor to an all-out assault on Homs, except for the pesky fact that the regime has never treated civilian casualties as cause for restraint.

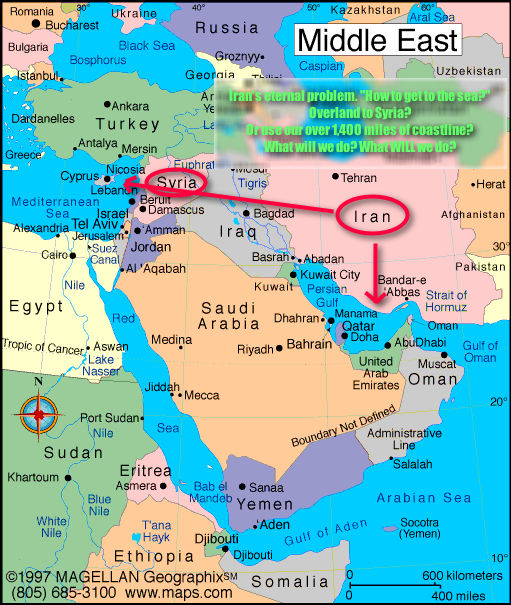

During a class on the contributions of Sun Tzu and Sir Basil Liddell Hart to modern military strategy, an alternative explanation emerged in the midst of discussion. The target of this new barrel bomb strategy is not civilians, nor rebel forces themselves but a well-calculated plan to disrupt the equilibrium of the Free Syrian Army. By conducting this campaign at the precise time the rebels are gathered in the same place as John Kerry and Ban Ki-moon, the regime is subtly and chillingly reminding the FSA that war crimes will not bring any semblance of armed intervention. Moreover, by demonstrating the capacity to both commit these crimes and simultaneously conduct diplomacy, it is tricking the assembled dignitaries into acknowledging the regime’s sovereign role.

In other words, with every barrel bomb that is met with little more than toothless opprobrium the FSA hears a singularly demoralizing message: you are alone.*

In fact, this strategy coincides neatly with the overall usage of barrel bombs since their introduction in the Syrian conflict in August 2012. For example, the first evidence of these attacks took place just after resignation of UN envoy Kofi Annan — which is generally attributed to his frustration with the absence of a unified international stance against Assad — and just before President Obama drew his now-infamous red line. Although difficult to verify, it seems that usage of these devices took a back seat for about a year, only to reappear with a vengeance in late September 2013; in other words right after 1,400 civilians were killed in a chemical weapons attack and the US struck a deal with Russia instead of unleashing the air strikes the rebels had been banking on.

Since then, they have become an all-too-common feature of strikes on rebel areas, particularly FSA strongholds in Aleppo and Hama. And cry as they may about the barbarity of the regime, there is little suggestion that game-changing help is coming — perhaps a few more light arms, ammunition and some anti-tank guns, but nothing that will alter the balance of military power.

And based on the recent back and forth over the possibility of the rebels getting the types of weapons needed to repel these weapons of homemade destruction, it seems the regime’s strategic calculations were right. Meanwhile, the regime is deftly leveraging its diplomatic engagement in Geneva to reinforce its sovereign right to decide how force is used, not used and whether its subjects will be allowed to seek shelter or exercise their right to stay with the rebels and die.

*Credit for this statement belongs to Jonas Motter, a recent grad from UC Santa Barbara who has just joined the Master of Global Affairs program at AUC.

0 comments

Glad to see a post address the increased use of barrel bombing by the regime at precisely the same time they’re engaged in diplomacy. My guess, however, is that if barrel bombs are as ineffective as claimed, than the decision to use them is more about capacity than sending the FSA signal that they’re alone. To be sure, conventional wisdom would be that Assad would play his capability cards close to his chest to increase his chances at securing a preferable outcome. Still, why the need to send a message to the FSA? Did the August 2013 chemical attack not already send that exact signal? If anything, then, the puzzle is what leads warring parties to send costly signals that have little military utility and can actually harm their position by mobilizing neutral individuals, giving third parties reason to reconsider their support, and/or harm their position at the negotiating table.

Correction. The last sentence should read as follows: If anything, then, the puzzle is what leads warring parties to *CONTINUE* to send costly signals that have little military utility and can actually harm their position by mobilizing neutral individuals, giving third parties reason to reconsider their level of support, and/or harm their position at the negotiating table.

I remember something I read elsewhere about Franco during the war. Apparently he deliberately refused to reign in some of his army’s abuses deliberately, so that the soldiers and officials had no choice but to remain loyal to him and with no option but to win. Not saying that’s happening in Syria, simply that it’s a possibility.

The argument that the regime is bombing as the peace talks go on as a demonstration intersects with these remarks by Ambassador Power, who notes:

“Reportedly, nearly 5000 people have been killed just since the Geneva II talks began. That is the most concentrated period of killing in the entire duration of the conflict – that’s just in the last three weeks – so it is not enough for us to stand here and say there has been no progress, which there hasn’t, we must recognize and state very forcefully that the situation has gotten worst, and is getting worst.”

At the very least the Assad regime doesn’t see the talks as any constraint on its military strategy, probably because it judges ongoing talks to make any real intervention effort less, not more, likely.