By Cassy Dorff for Denver Dialogues

To get to Vermont from Denver all you need is a good car and a lot of patience. It is about a 2,000-mile drive. Not too bad. To head 2,000 miles south and travel from Denver to Ayotzinapa, Mexico you would need a good car, patience, and some extra luck in navigating a violent drug war. Make no mistake: in Mexico, the people and the land are beautiful; the food is incredible; the culture is heart-warming, vibrant, and inviting. But the Mexican Criminal Conflict is real and a small group of survivors are here to tell you about it.

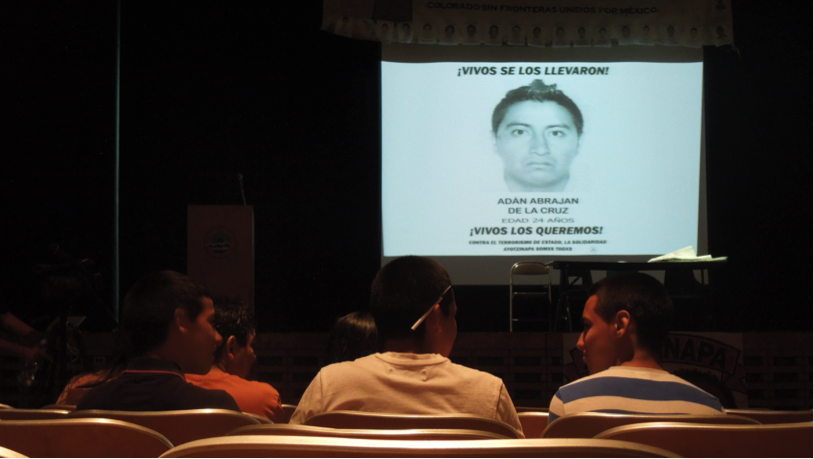

In September 2014, local police stopped students of Ayotzinapa’s Normalista teachers’ college in Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico. The police shot at the students, killing six and injuring 25. Survivors reported that those who were unable to escape were forcibly loaded into trucks and taken away. That night, 43 students disappeared and today the whereabouts of these students is unknown. The motives behind these crimes remain uncertain. The government’s official story is that the mayor of Iguala and his wife ordered the attacks against the students but after several official and unofficial investigations the families of the missing students are still searching for the truth. This violent tragedy has now become a symbol of the greater criminal conflict in Mexico where roughly 100,000 people have been murdered and another 25,000 have disappeared in the last 8 years. The families of these missing young men now comprise Caravana 43, a social movement organized as a call for justice and accountability from the Mexican state.

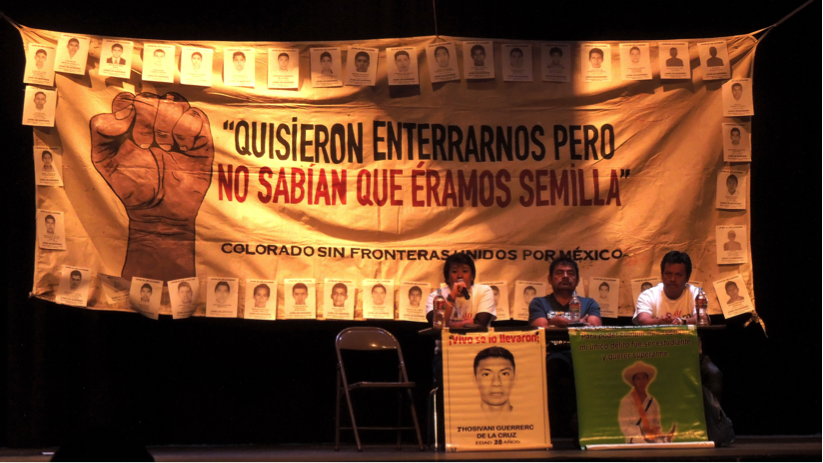

I attended the Caravan’s event in Denver on April 12th. In all likelihood, the Caravan is coming (or has already visited) a town near you.[1] At the event, the families told their stories of loss and of government corruption, incompetence, and crime.[2] The complete list of Caravana 43’s key goals and “talking points” are easily accessible from their website. A deeper presentation of events surrounding the missing students can be found by watching a quick VICE documentary.[3] In this post, I am not going to explain, in detail, the timeline of events that inspired Caravana 43 into existence. (A timeline can be found here). Instead, I want to focus on why Caravana is here, in the United States, and how support from both individuals and organizations in the U.S. has the potential to influence the success of the movement.

Recently, at a workshop hosted by the Sié Chéou-Kang Center for International Security and Diplomacy at the University of Denver, folks discussed how social movements and civil resistance campaigns are influenced by support from other non-state actors.[4] As it turns out, we know little about what kinds of support influence the success, duration, or evolution of civilian movements. This is partly because it is difficult to observe how a movement obtains and sustains support from different actors both nationally and transnationally. By traversing the United States, Caravana 43 is directly reaching out to establish awareness and supportive transnational connections. As such, researchers are in a unique position to observe and learn how transnational recognition and external support—both through material and immaterial means—alters the future of this movement.[5] To try to better understand how these connections are established and how support from people in the United States will aid the movement, I interviewed a local organizer in Colorado—Ismael Netzahuatl—who helped bring the Caravan to the area.

[Please note: The interview was conducted in Spanish, over email. All opinions of the interviewee are his own. My questions are written first, followed by Netzahuatl’s response in italics.]There are several key goals of the movement. I would like to discuss concrete ways in which the group seeks external support from both people in the United States and the U.S. government. First, can you introduce yourself?

Hello my name is Ismael Netzahuatl, I am a member of Colorado sin Fronteras Unidos por Mexico and I am the creator of www.radiofiestamexicana.com. I joined Colorado sin Fronteras Unidos por Mexico to speak out against the Mexican consulate. We are all very tired of poor governance in Mexico, where a handful of families subject more than half of the population to poverty. This is what unites us and led us to organize. We held various fundraisers in order to raise money to achieve our main goal: bring la Caravana 43 to Colorado.

The Caravan lists pressuring the U.S. congress to change arms policy as a primary goal. For those in the U.S., can you elaborate on why the issue is key to the movement and how it came to be one of Caravana 43’s goals?

The American government economically aids Mexico in their fight against narco-traffickers through the Merida Initiative. The Mexican government uses this money to buy weapons to arm different political entities (municipal, state, and federal officials and—at worst—paramilitaries). Police and Mexican officials are so corrupt that they are often protecting drug-traffickers with these weapons. So when someone (such as a journalist, teacher, student, or common citizen) points out this unbridled corruption and then that same person is disappeared, murdered, or tortured, Caravana 43 denounces these injustices and aims to keep track. The Caravana wants to end this policy because this policy is responsible for the disappearance of their children!

There is a call for donations at the events and online. How successful has Caravan 43 been in gathering donations, and is there a goal amount Caravana 43 hopes to raise? Do the organizers feel that donations are critical to sustaining the movement? Besides individual donations, has the movement been able to secure donations/financial support from other organizations or movements?

We do not know what the fundraising goal of Caravana 43 is, but we do know that the organizers believe it is essential to encourage fundraising because the Caravan members are people who have left jobs at farms, small businesses, or their families in order to speak here in the United States. To help support this movement, various support organizations were created in each U.S. state hosting the Caravan. These organizations help provide and pay for accommodations, meals, transportation, and other logistical costs. Many organizations across the country have reached out to help the Caravan, though I do not have a list of these organizations.

At this point in the caravan’s tour has the group had any support or response from U.S. policy makers (at any level of government)?

Caravana 43 members have not received any political support (perhaps they do not know the best way to reach them or they decided not to approach them). The Caravana 43 members have only received community support.

How did this the tie between Colorado sin Fronteras Unidos por Mexico and Caravana 43 form?

We simply reached out to them and asked if we could bring them to the Colorado area!

What else would you like to share with our readers (which tend to include practitioners and researchers)?

I would ask the citizens of this country to be vigilant, to ask their government how their tax dollars are spent. Drug trafficking only ends when this country stops consuming. Furthermore, the “fight against drugs” has never seen positive results and instead has left a trail of pain, death, and suffering among the poorest people in Mexico, which are the majority! Politicians and policymakers have a duty to respond to the questions and demands of citizens!

[End interview].A main take away from attending these events and from the interview with Ismael is just how important organizers feel international attention, and specifically recognition by Americans, is to the success of the movement. There is a clear logic here: the U.S. is powerful and directly influences the Mexican government. If people living in the U.S. can come to care deeply about the human rights abuses on going across Mexico, then they will pressure their government to pressure the Mexican government to be accountable for their failures. More attention from the United States also brings greater organizational attention and resources for addressing human rights abuses, monitoring elections, and establishing justice. At the very least, members of Caravana 43 want to be heard and to end the cyclical violence that has damaged Mexico over the last decade; as one father of a missing student said, “if we are quiet we will live the same thing again and again.”

[1] The Caravan is now touring Europe and Canada. [2] There will soon be video footage of these testimonies here. Translation pending. Check back soon for English subtitles! [3] While there are many films on the subject, the Caravan screened this film during their recent visit in Denver. I would also recommend listening to Radio Ambulante’s podcast about Ayotzinapa (or reading the English translation provided on the website). [4] One of the workshop attendees, Maria J. Stephan, has co-authored a USIP report on the topic. [5] Speaking of research on Mexico, I should mention that there are several bright-minded folks doing interesting and timely work on the Mexican conflict. Check out Sandra Ley Gutiérrez, Janice Gallagher, or Alice Driver to learn more.

1 comment

Reblogged this on stopyourstoryisntoveryet.