Guest post by Lee Cotton and Cassy Dorff for Denver Dialogues.

Overview: Drug-trafficking organizations (DTOs) have long been active throughout Latin America. A rise in cocaine and marijuana production shifted critical foci of power into regions of Colombia during the 1970s and then into Mexico during the 1990s. It was during the early 2000s, however, that US-Mexican policy towards drug trafficking took a dramatic turn from previous decades. In an upcoming policy brief soon to be released by the Sié Center, we use actor-coded event data to map the effects of this policy change on the dynamics of violence between DTOs and government actors.

Context: Under the visage of national (and regional) security, President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) deployed tens of thousands of troops across the country; he sent some 4,000 troops to his home state of Michoacán ten days after assuming office in December 2006 due to the increase in drug-related violence in the region. Using this “la mano dura” approach against the network of cartels, President Calderón and the Mexican military targeted the four primary groups at the time: the Gulf Cartel, the Juárez Cartel, the Sinaloa Cartel, and the Tijuana Cartel. The US government, motivated by Mexico’s strong position, entered into a security cooperation agreement known as the Mérida Initiative in 2008. The initiative provided Mexico with federal aid from the US in order to train soldiers against DTOs, access US intelligence capabilities, and eventually provide educational assistance and other programs to rectify Mexico’s broken judicial system. At the outset of the agreement, the US and Mexican governments agreed to channel $116.5 million in military assistance; this accounted for more than a quarter of the funding allowed for the first year ($400 million).

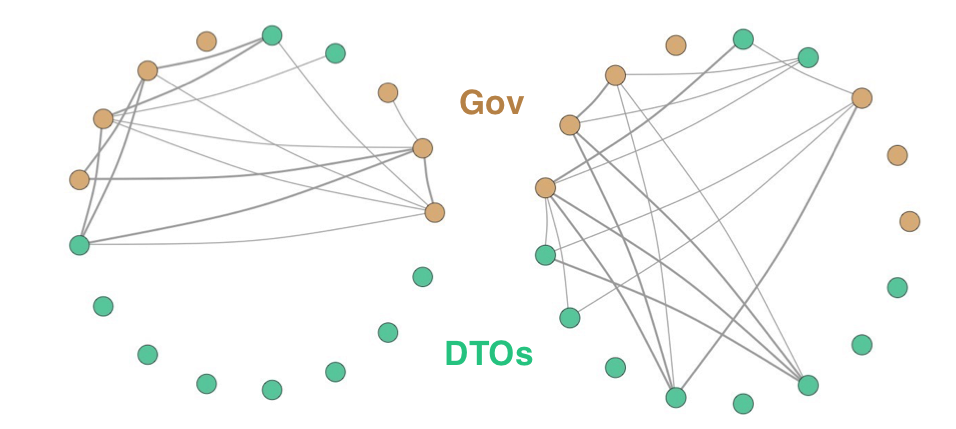

Event Data and Networks: Using network analysis of machine-coded data from 2005 to 2013 (the year before Calderon entered office and the year after he left) our analysis describes trends in violence as it relates to the criminal conflict, and challenges the effectiveness of Calderón’s military strategy. The findings confirm analysts’ claims that Calderón’s deployment of 10,000 soldiers and nationwide employment of federal police did not eliminate the four primary cartels, but instead caused them to fracture into more volatile organizations, increasing competition between armed groups, and elevating violence against civilians.

Our research identifies actor-coded conflict event data that occurred in Mexico from 2005-2013. It accounts for which actors—government groups such as the military or Special Forces and DTOs—were involved in each conflictual event (“Conflictual event” is defined here following Philip Schrodt’s CAMEO ontology which identifies verbs related to assault and violence within text). To record this information, we analyzed the ICEWS (Integrated Crisis Early Warning System) data and (when possible) expanded on the original data using newspaper articles, magazines, and other open source documents. We also created new actor dictionaries; drawing on preexisting data measuring DTO operation areas at the municipal level, we matched stories involving vaguely referenced DTOs with their known area of operation. The result is an event database of roughly 1,000 actor-coded events from 2005-2013.

Mapping the Effects of a Militarized Policy: When President Felipe Calderón took office in 2006, he pledged to crack down on organized violence within Mexico’s borders. As previously stated, he deployed the Mexican Armed Forces to combat cartel influence and violence. However, this campaign quickly backfired as homicide rates rose, cartels became more violent and, in some cases, even fractured to form smaller DTOs. Our data captures the beginning of this backfire with rise in violence between 2006 and 2007, and shows an almost 50% rise in conflictual events for the following year. The network in Figure 1 maps this increase in violence and reveals more cartel groups are active following the militarized campaign.

This overall rise in violence can be directly tied to the heightened military presence across the country. As military outfits began policing cities and targeting DTO leaders, DTOs responded by retaliating with even more severe violence or by competing against one another in order to assume stronger control over communities and resources.

Furthermore, our analysis reveals the ways in which the Mexican government’s response to drug trafficking organizations increased the complexity and intensity of the conflict. For the duration of his single, six-year term in office, the total number of homicides jumped to an estimated 120,000—doubling that of homicides during President Vincente Fox’s tenure. It is important to note that despite the rise in violence, our data captures the downfall of a specific cartel relative to the others: the Beltran Leyva Cartel. Police officers killed the head of the organization, Arturo Beltran Leyva, in December 2009, which led to the end of significant violence on the part of that group in 2011. However, the Beltran Leyva Cartel found new life under another name, the South Pacific Cartel, with some of the organization’s former leadership.

Moving Forward: There are two key avenues for improving Mexican national security: community engagement and transparent institutions. Programs that focus on community awareness, education, and social inclusion prepare citizens against extortion by DTOs. Our research and other literature demonstrate that the influence of military force only makes regions more prone to violence. Military takeover of local, state, and federal law enforcement is not an effective policy to stem DTO related violence. Calderon’s strategy was a failure in that it placed all the resources against the cartels in the hands of the military rather than addressing civilian needs, such as local institutions that foster justice and security. Strong, transparent judicial systems hold both judges and those on trial more accountable for their actions.

The judicial system in Mexico is opaque and corrupt; parts of the Mexican judicial branch continue to operate under the pretense of closed-door trials, written arguments, and long pre-detention times. President Calderón initiated judicial system reform in 2008 in conjunction with the Mérida Initiative, but not all states have accepted the reforms, which demand a public trial system with oral arguments. Some of the most volatile states—Guerrero, Michoacán and Tamaulipas—have yet to fully implement the new reforms. President Peña Nieto will continue to face challenges against nationwide judicial reform as long as Mérida funding continues to be implemented with an emphasis on military training and support. As of 2013, only 18 of 31 states (plus the Federal District) had begun reformation.

Lee Cotton is an MA Candidate in International Security at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver. Cassy Dorff, PhD, is a research fellow at the Sié Chéou-Kang Center for International Security and Diplomacy at the University of Denver.

1 comment