Guest post by Nico Ravanilla, Renard Sexton, and Dotan Haim

Last month, a brutal police killing in the Philippines was caught on tape, sparking a nationwide debate about extrajudicial violence and police conduct. The killing followed an announcement by the International Criminal Court that there is a “reasonable basis” to believe that crimes against humanity were committed during Philippine President Duterte’s infamous war on drugs. By official figures, about 8,000 people have been killed in drug crackdowns since 2016, although independent estimates are higher. In the last two months alone, as COVID-19 numbers rose across the Philippine islands, at least 12,400 were arrested and 119 killed. President Duterte himself is happy to take credit for the bloodshed, declaring to the media: “I’m the one… you can hold me responsible for anything, any death that has occurred in the execution of the drug war.”

That the drug war would be so brutally carried out may seem obvious in retrospect—internationally Duterte has become almost synonymous with the violent anti-drug crackdown. But, in fact, policing in the Philippines is highly decentralized and, generally, not very efficient at implementing nationwide orders. Many past Filipino presidents and populist leaders worldwide have announced sweeping national policies, which local officials politely endorse but then ignore, with no significant changes in their day-to-day operations. Our new research shows why Duterte’s drug war was different: although President Duterte had almost no allies at the local level, he mobilized a network of outsiders by dangling the possibility of joining a new political network organized around him.

The local politics of policing

Although nominally a nationalized police force, the Philippine National Police (PNP) is in practice a set of 1,488 semi-autonomous municipal police chiefs, who are accountable to the local mayor in addition to the police chain of command. As a political outsider, President Duterte had very few allies among the nation’s mayors when he took office: just 1 percent of mayors belonged to his political party (PDP-Laban). And although public support for the war on drugs has stayed consistently high, local mayors and police chiefs who aggressively follow the policy ran the risk of alienating their constituents and opening themselves up to future legal claims once Duterte is out of office.

Thus, from the outset Duterte faced significant barriers to ensuring his orders were implemented, as is the case in many contexts where national policies fail to be realized once they reach the local level. For longtime observers of the Philippine police, it was a puzzle: how were the Duterte administration and the PNP able to so rapidly and aggressively ramp up the drug war?

Patronage networks

Politics in the Philippines is driven by patronage networks. If you are connected to the people in charge, you can get preferential access to public expenditures, hand out contracts to your cronies, and secure re-election when the next balloting comes. If your buddies are swept out of power—or you never had friends in high places in the first place—things are considerably more difficult for you as a local politician.

In 2016, when President Duterte was elected, the insider political network was organized around the Liberal Party (LP), which was the party of the outgoing president Noynoy Aquino. Unexpectedly, then-Davao City mayor Rodrigo Duterte won the election as a political outsider who had very few allies at the national level. Among mayors, who were elected at the same time as the presidential contest, 747 were elected on the LP party line, whereas just 19 belonged to Duterte’s party.

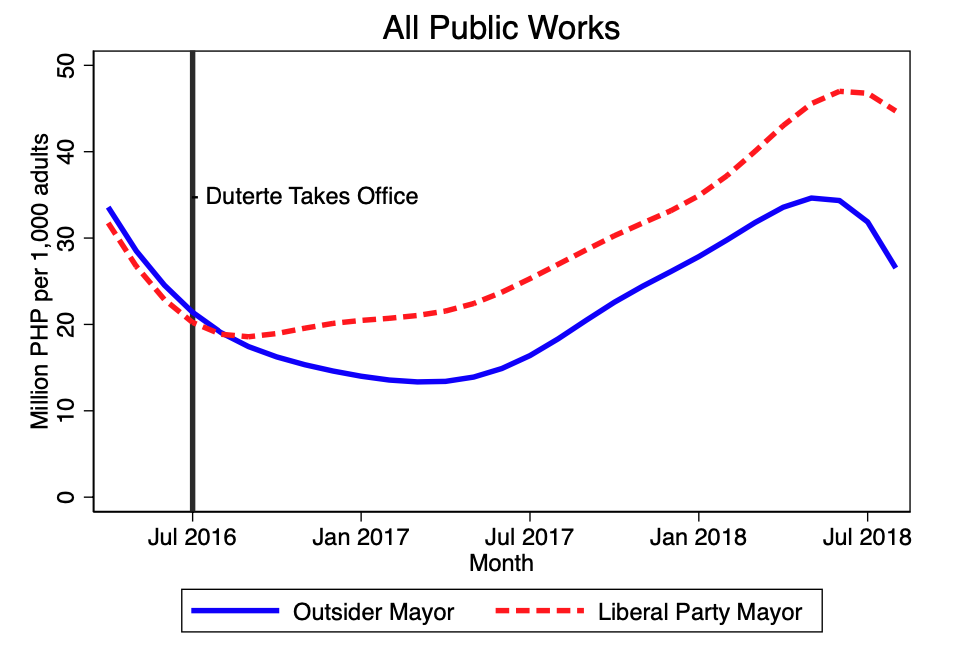

For mayors outside the LP network, public spending from 2016 to 2018 was hard to come by. Over the first two years of the Duterte administration, mayors elected at the same time as the president but from small parties or as independents received 40 percent less public works appropriations than insiders associated with the LP network. This resource gap is a typical one for outsiders, who usually find it considerably harder to achieve re-election than those connected with an insider network. In the half dozen elections before the 2019 midterm, outsider mayors (those not connected with the primary patronage network of the era) were half as likely as insiders to get re-elected.

The drug war as a political lifeline for outsider mayors

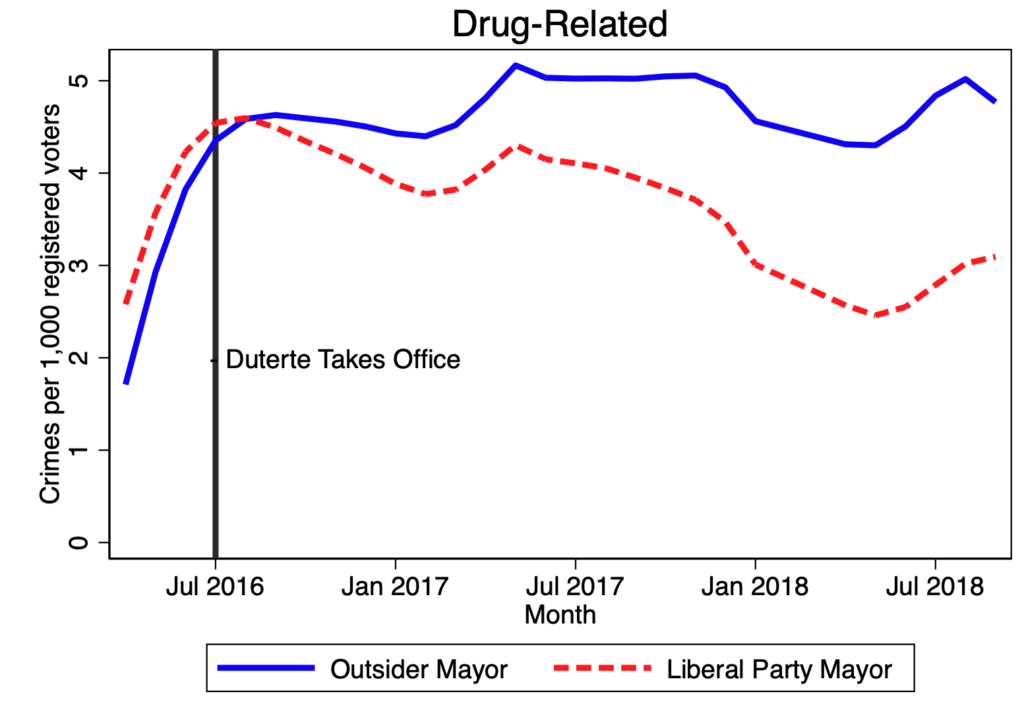

Sensing that the president’s drug war was an opportunity to circumvent the existing patronage network to appeal directly to an outsider president, our research finds that outsider mayors executed the drug war much more aggressively than LP mayors, with 40 percent more drug-related police incidents and 60 percent more extrajudicial killings by police, even as the overall level of crime enforcement did not change.

These outsider mayors were rewarded politically when the 2019 midterm elections rolled around last year. For the first time in decades, incumbent outsider mayors improved their vote shares relative to insiders, in part because they were allowed to run under the President’s party (PDP-Laban). The midterm election cemented a new political network, with President Duterte at the helm, organized in large part around his most ardent supports, who were willing to take the risk of strongly embracing the controversial war on drugs.

Populists need local allies

In democracies around the globe, populists have won office in recent years on the strength of norm-defying signature policies, such as anti-immigration campaigns by US President Donald Trump or Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. Some of those policies can be implemented unilaterally at the center, but many require allies throughout the political system—something that outsiders, by definition, often lack. Counterintuitively, it is the norm-defying nature of populists’ signature policies that allows them to weed out “loyal” allies from temporary supporters and effectively implement their agenda.

Nico Ravanilla is an Assistant Professor at the School of Global Policy and Strategy at UC San Diego. Renard Sexton is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Emory University. Dotan Haim is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Florida State University.