Peter Katzenstien’s 1990 monograph, West Germany’s Internal Security Policy: State and Violence in the 1970s and 1980s, provides several passages that make rather interesting in the context of contemporary Western democracy’s responses to the 9/11, 11 M, 7/7 and more recent terror attacks.

Let’s begin with the terror attacks. Three distinct waves of West German terrorism (1970-2, 1974-77, 1984-6)

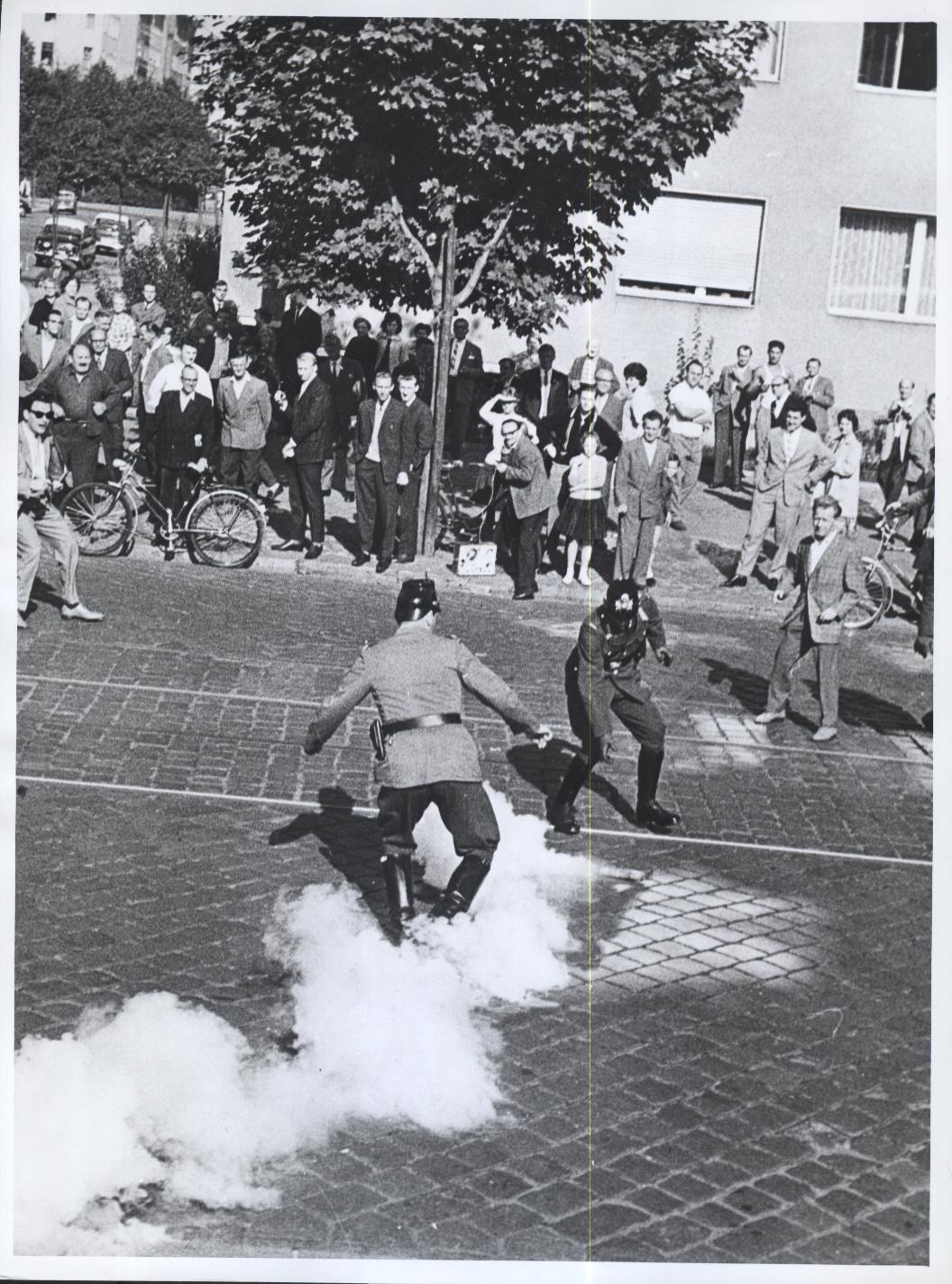

triggered a set of political responses that shows a remarkable degree of coherence during the last two decades…Important elements of the organizational structure and operative mission of the West German police have changed from a military to a civilian model informed not by the image of fighting a civil war, but of controlling mass protest and surveying clandestine operation (p 1).

How many attacks were there? Estimates vary widely,

[b]ut the most conservative… counts over 3,000 incidents between 1968 and 1987… In the period 1967-72… police counted more than 90 shootings and bombings. Between 1970 and 1979 government figures report 649 left-wing terrorist attacks with 31 persons killed, 97 injured, and 163 seized as hostages…Between 1980 and 1985 the total number of terrorists incidents committed by both the Right and the Left increased to 1,601 (pp 1-2).

How many dissidents produced this mayhem?

In the absence of reliable data on the number of terrorists in the Federal Republic, the West German media typically repeat the the 1980s government estimate of about 20 activists, 200 sympathizers who may help by providing money, apartments, or automobiles, and a supportive social mileu variously estimated at between 2,000 and 20,000 from which sympathizers and activists are apparently often recruited (p 2).

Let’s now examine the components of the West German government’s response.

[T]he crucial development in the 1970s centered on the growth of a large, sophisticated, computerized information system that stored data on a growing number of West Germans. After an initial, technocratic euphoria about entirely new dimensions of police work had passed, the West German police still was equipped with new instruments of gathering, storing, retrieving and evaluating vast sets of data on particular social groups or suspects (p 17).

The new technological capacities of the police have created new forms of police work that have transformed relations between the police and society…Surveillance of potential suspects or of demonstrators suspected of violence and undercover activities have become accepted methods of police work (p 20).

[A]fter its legalization for the purpose of intelligence surveillance in 1968, wiretapping by the police has become a relatively routine affair (p 35).

Ten amendments to the criminal code, passed between 1970 and 1989, have granted the police and the judiciary an increasing number of instruments to respond to the rise and persistence of terrorism…Furthermore, the Bundestag also changed the criminal code between 1974 and 1976: to make it easier to arrest those suspected of terrorist crimes (p 32).

What was the impact of this remarkable expansion of police surveillance and erosion of civil liberties?

More intrusive if less overtly repressive policing domestically proved to be of limited use at the height of West Germany’s second terrorist wave in 1976-77. More than 100,000 police officers and members of West Germany’s various security organizations were trying to catch two or three dozen terrorists (p 48).

The new forms of police surveillance have created considerable strains on the German notion of the lawful state. Numerous pieces of legislation dealing with questions of internal security have been one result; numerous security scandals another (p 46).

West German terrorists, furthermore, adapted to the new police procedures, and in the 1980s the police have learned remarkably little about the structures, mindset and strategy of the groups operating in the underground (p 66).

Given the paltry return on investment, why did West Germany continue to expand police budgets, personnel and powers? It seems to me that it is good constituent service: terror attacks generate a disproportionate fear response among the public, and legislation and larger budgets are visible policy responses that politicians can take to demonstrate that they are taking action to “keep the public safe.” The fact that the spending is wasteful and rights are eroded is beside the point. That is why public education and activist campaigns to bolster rights protection are so important.

* A previous version of this post appeared at Will Opines.