By Cullen S. Hendrix for Denver Dialogues.

Note: this is a guest post. I’ll be returning to the Challenges of Responsible Engagement issue in future posts.

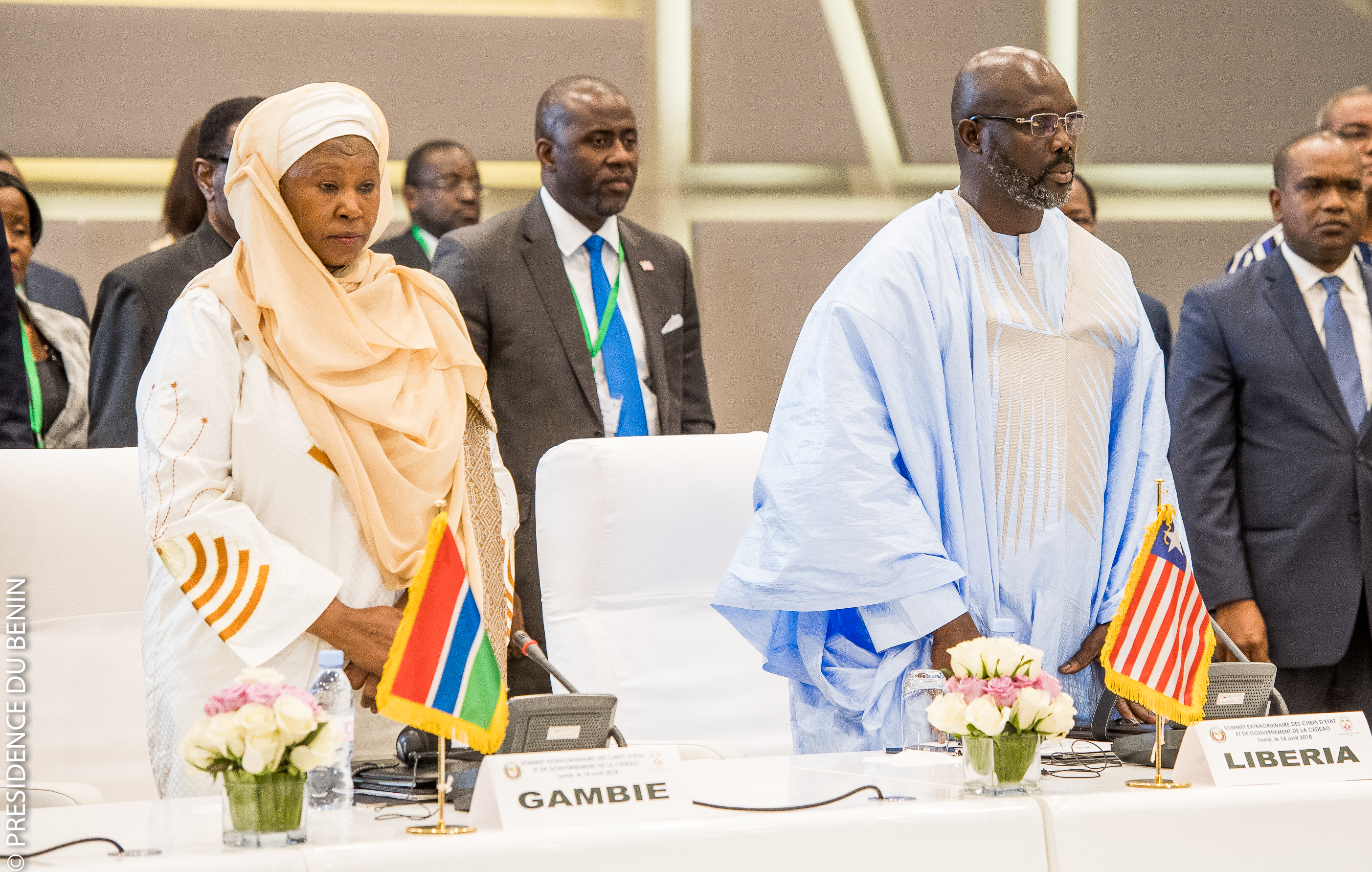

As one of the world’s most talented footballers of the 1990s, Liberian President George Weah is no stranger to roaring crowds. But recently, these crowds were less than supportive: Weah’s administration has faced mass protests—and threats of more to come—due to its inability to address skyrocketing inflation and food prices.

This is at least the second time that food prices have been implicated in mass protests in the past few months. In Sudan, food prices were one of the animating forces behind the mass protests that resulted in the ouster of Omar al-Bashir in April. In both cases, the problem is seen as a symptom of broader economic mismanagement. But the policy responses—or lack thereof—are emblematic of systematic differences in the ways autocratic and democratic governments attempt to address grievances related to the classic “kitchen table” political issue.

In Sudan, al-Bashir’s government sparked protest back in December 2018 by rapidly removing state subsidies on the price of bread, which caused it to triple overnight. As anyone who follows US politics knows, subsidies are arduous to remove once put into place. But they are even more of a third-rail issue in developing- and middle-income autocracies, like Sudan, where cheap food is part of the grand authoritarian bargain. Instead of offering the populace a say in government, the ruling party provides them—especially those living in urban areas—with access to cheap food and other basic consumer goods like cooking oil and gasoline. Authoritarian governments systematically engage in more pro-consumer (and anti-producer) agricultural and food policies. This is a classic example of good politics being bad economics: in order to shore up political support in critical urban areas, many authoritarian regimes systematically impoverish their rural areas and festoon benefits on middle-class urbanites. It’s one of the reasons that authoritarian governments are less likely to see protests in times of high global food prices—but when price spikes do make their way to consumers as they did in Sudan, as Halvard Buhaug and Todd Smith have shown, they are more likely to protest and riot.

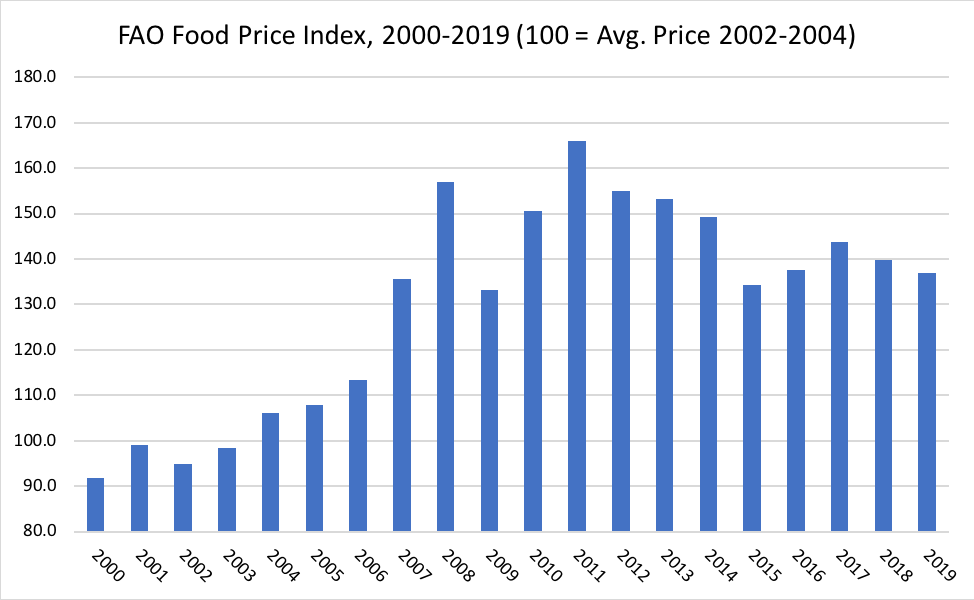

In Liberia, the culprit is a depreciating Liberian dollar, which has caused the real cost of food, especially imported food like rice, to increase dramatically. According to recent estimates, over two-thirds of Liberia’s cereal consumption is fed by imports. Because of this, high prices in global markets—which are down relative to near-historic highs in 2011 but still more expensive than at any time in the 1990s or early 2000s—translate very quickly to pain for Liberian consumers. President Weah called for a national roundtable in response to the protests, and his government is in ongoing talks with the IMF to develop a comprehensive plan to restore economic growth and tame inflation.

If history is any guide, it is likely that Weah’s administration will not resort to generalized food subsidies to attempt to stem the protests. Food subsidies are a massively inefficient way to address food insecurity and price spikes, with many of the benefits accruing to comparatively better-off middle-class households that do not need emergency assistance. Instead, best practice is to use means-tested targeted transfers, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in the United States, that target benefits at those households that need them most. Indeed, this is what Liberia did during the 2008 food price spike, during which the government sought to address the crisis through removing tariffs on food imports and trying to ensure food access for the poorest, most at-risk households instead of offering general food subsidies. If Weah’s government follows suit, it will be consistent with a broader trend: democratic governments are less likely to use general subsidies to cushion urban consumers from high prices.

This will be good policy—and more economically sustainable, as targeted transfers are more efficient and less costly—but may not be good politics. Typically, it is not those food-insecure households that take to the streets, but rather the comparatively well-off middle classes that would be missed by these targeted transfers. Thus, confronting high prices, the Weah administration may face a tradeoff between policies that will curb protests and policies that will address the needs of the most food-insecure.