By Will H. Moore.

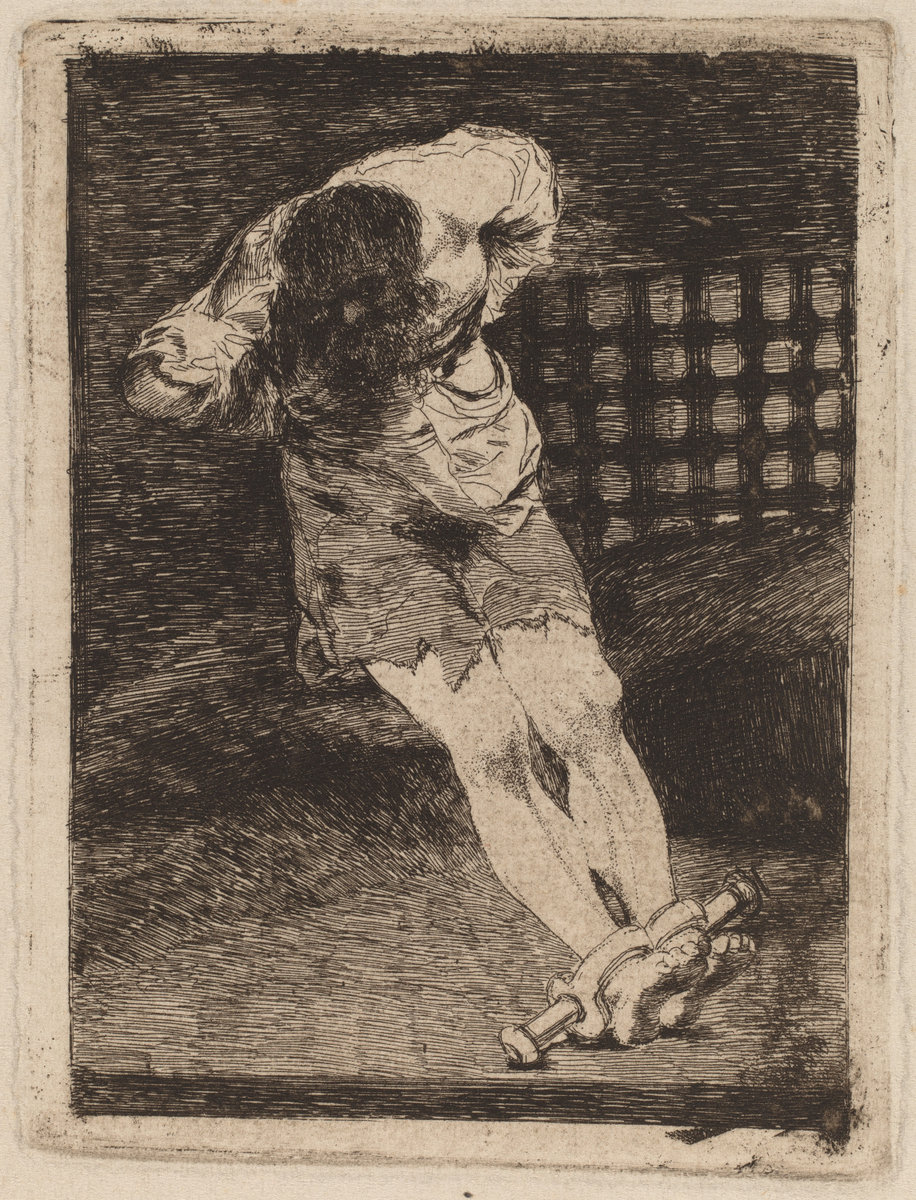

I knew locking a man up in a dark room was meant to arouse fear before torture; hoping they’d begin with the bastinado, I thought about the lies I could tell to save my hide.

The speaker is Black, a character in Orhan Pamuk‘s 1998 novel My Name is Red. The passage, which I continue below, offers a useful window into the central claim Steven Pinker makes in his book about the centuries-long decline in homicide produced by governments’ gradual ability to enforce what the sociologist Max Weber called a monopoly over the legitimate exercise of coercion. The idea is that humans treat one another differently when a third party is watching.

More specifically, as governments established first criminal courts, and later police and public prosecutors, people began to exercise self-restraint during interpersonal conflict, and homicide declined. State failure produces a spike in killing, whereas the less corrupt are courts and police, the lower is the homicide rate. In a phrase, governments that are able to effectively enforce their claim on a monopoly on violence incentivizes us not to murder one another.

What role does torture play? It turns out that torture was widely used in courts and other judicial proceedings as the means to establish the innocence/guilt of accused throughout human societies up to the 18th Century. Further, the decline of torture occurs during the rise of public police forces during the 19th Century. Finally, criminal courts that rely on forensic evidence (American readers should think “Perry Mason,” “Adam 12,” “Law & Order,” “CSI,” etc.) are a post-1920 development.

Pamuk’s fictional, which takes place in Istanbul circa 1590, provides us with an account of how a Sultan who had no public police nor standing courts used a combination of torture and collective punishment to try to keep a lid on the murder rate. Let’s return to the novel.

Two murders had taken place among the painters (miniaturists) in a shop that was working on a book the Sultan had commissioned. One of those painters, Black, has been detained.

They took off my vest and shirt. One of the executioners sat on me, driving his knees into my shoulders. Another placed a cage over my head with all the practiced elegance of a woman preparing food and began slowly turning the screw at its front. Nay, it wasn’t a cage, but rather a vise that slowly squeezed my head.

I screamed at the top of my lungs. I begged, but incoherently. I cried, mostly because my nerves had given out.

They stopped momentarily and asked: “Were you the one who killed Enishte Effendi?”

It is a judicial inquiry: no police force exists to investigate, nor prosecutor, nor judges, so the Sultan turns to the medieval process known in Europe as Trial by Ordeal (aka, Trial by Fire). The Spanish Inquisition and Salem Witch Trials are widely known events that featured trial by ordeal, but few realize that trial by ordeal was the standard judicial process for centuries throughout most of the world where recorded history provides a record.

Black continues.

I took a deep breath. “Nay.”

They began to tighten the vise again. It was excruciating…

“Who then?”

I don’t know!”

I wondered if I should just tell them I’d killed him. The world spun unpleasantly about my head. I was overcome with reluctance.

Then, suddenly, Black is released. Why? He had passed the ordeal: suspects were subjected to a predetermined level of pain, known only to the torturers. If s/he did not confess, she was deemed not guilty, and another suspect would be subjected to trial by ordeal.

Here is what happens next.

“Our Sultan has ordered that you not be tortured at this time,” said the Commander. “He deemed it more appropriate for you to help the Head Illuminator Master Osman find the rogue who’s been killing His miniaturists and the loyal servants preparing His manuscripts. You have three days in which to interrogate the miniaturists, scrutinize the illuminated pages they’ve made and find the sly culprit.

Within three days, if you fail to produce the swine along with the missing page he stole–about which much gossip is flying–it is Our Just Sultan’s express desire that you, my child Black Effendi, be the first to undergo torture and interrogation. Afterward, let there be no doubt, each of the other miniaturists will have his turn.

Everybody knows that when a crime is committed with Our Sultan’s wards, regiments and divisions, the entire group is considered guilty until one morning one among them is identified and turned in. A section that fails to name the murderer in its midst goes down in the judicial records as a ‘division of murderers,’ including its office or master, and is punished accordingly.”

The Sultan was, in effect, deputizing Black (and Master Osman) to conduct an inquiry to determine who was the guilty party.

Why? Because the government had no police force and no prosecutor/court, murder investigations and prosecutions took place on an ad hoc basis. Given the absence of modern institutional solutions to homicide, alternative systems were necessary.

To summarize, in the Sultan’s realm the problem of homicide was addressed via a mixture of ad hoc investigations, trial by ordeal, and self-policing motivated by collective punishment. One need only have been a tweenager (middle schooler), not a rational institutional theorist, to understand why such a system is more brutal, and a less effective deterrent, than the flawed, but superior, “monopoly” alternative.

Pamuk’s scene wonderfully captures why, as Pinker explains, the government’s claim on a monopoly on the legitimate exercise of coercion, enforced via the creation of professional police and courts, has not only dramatically reduced the homicide rate in our species, but also why we have driven torture from our legal systems as a sanctioned practice.

@WilHMoo

A previous version of this post can be found at Will Opines.

2 comments

On the other hand, torture is still used by governments, and is recommended by many important people, such as those recently competing for the Republican presidential nomination in the USA. I wonder if aggregate torture has declined, or just been hidden.

Indeed. These posts may be of interest:

“Most countries are against torture — but most have also been accused of it.”

http://wapo.st/22AuGH4

“Why Democracy Does Not Always Improve Human Rights,”

http://www.scholarsstrategynetwork.org/brief/why-democracy-does-not-always-improve-human-rights