By Jonathan Pinckney for Denver Dialogues.

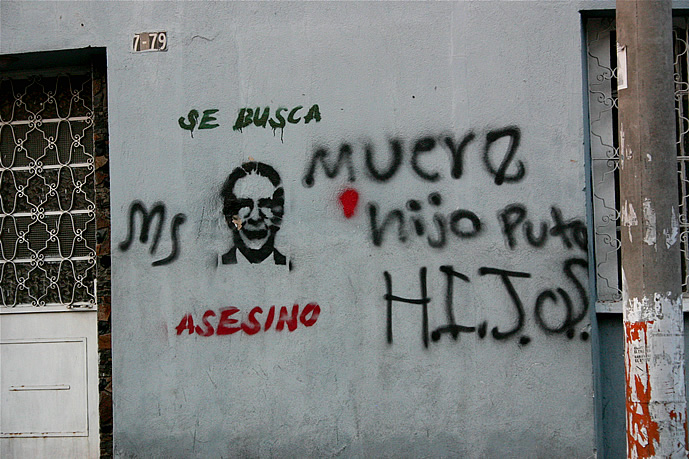

It’s a common story, seen in democracies and non-democracies, in every region of the world, from Charlotte to South Africa. An initially peaceful protest movement engages in violent clashes with authorities. Images of peaceful demonstrators are replaced by rioters with Molotov cocktails and rocks. Media reports tend to paint this as an almost inevitable consequence of government repression or protester disorganization. Of course, not all campaigns devolve into this dynamic. In some cases, such as the Nashville lunch counter sit-ins during the US civil rights movement, protestors have been remarkably disciplined even in the face of brutal repression.

In fact, the question of why some peaceful campaigns lose nonviolent discipline while others do not has been remarkably underexplored, at least in these specific terms. What separates the campaigns that maintain nonviolent discipline from those whose discipline begins to break down?

Using data from the forthcoming Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO) 3.0 dataset and three comparative case studies, I tested the impact of twelve different potential causal factors on the likelihood of anti-government resistance campaigns having nonviolent discipline breakdowns. I look at country-level attributes such as the history and repertoire of contention, campaign-level attributes such as hierarchy and goals, and individual protest-event attributes such as the repression and event-level concessions. Three key findings stand out.

1. Repression matters, but not in the way it is often described

The best predictor of breakdowns in nonviolent discipline is government repression, but the data tell a somewhat more complex story than a simple reactive violent exchange. Breakdowns in nonviolent discipline only become more likely when the rate of repression of nonviolent actions has been consistently high over a long period of time. This suggests that violent turns are not simply emotional “gut-level” responses to government brutality, but rather follow a more rational calculus by movement participants who see nonviolent action being met with government violence over and over again.

2. Concessions also present challenges

Government concessions are also associated with more breakdowns in nonviolent discipline. While data limitations kept me from digging into the mechanisms behind this in this piece, previous scholarly work suggests that concessions may split movements between moderate and radical factions, pushing radicals to “prove themselves” through violence.

3. A little disorganization may be a good thing

My initial expectation was that the more hierarchical and centralized a campaign was, the less likely a turn to violence would be. The data indicated the opposite. Resistance campaigns with hierarchically-structured leadership and low levels of observed internal disagreement were actually more likely to have breakdowns in nonviolent discipline than campaigns with more flat organizational structures and some visible policy disagreements. This supports the finding of scholars who have argued that nonviolent resistance is best facilitated and maintained by an open, participatory ethos.

So, when does nonviolent resistance “turn violent?” It’s not a simple matter of a lack of control or a reactive response to government violence. Instead, maintaining nonviolent discipline involves a complex set of strategic interactions between protesters, campaign leaders, and government authorities – including the degree to which activists prepare and train to absorb government repression over the long haul, the ways in which activists structure their campaigns, and their ability to mitigate against emergent internal divisions along the way.

Jonathan Pinckney is a PhD candidate at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies and a Research Fellow at the Sié-Chéou Kang Center for International Security and Diplomacy. This research was funded by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict.

3 comments

LIT