Guest post by Graig R. Klein, Carla Martinez Machain, and Efe Tokdemir.

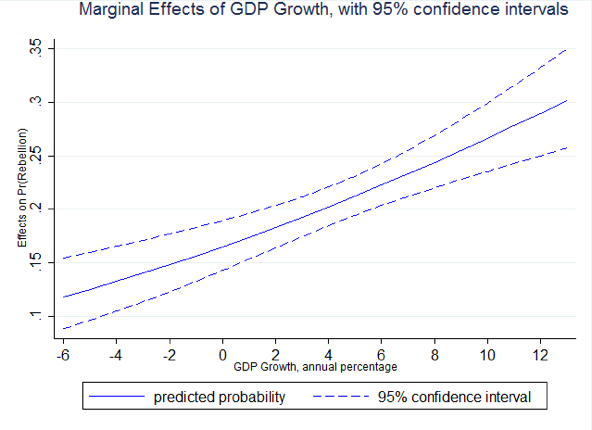

In an effort to rally political support during times of economic stagnation and decline, leaders may choose to exploit in-group–out-group tension as a means of avoiding, rather than tackling, economic problem(s). We have observed leaders around the world repressing ethnic minorities as a way to stay in power – see examples from Yugoslavia, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Ethiopia, Thailand, Nigeria, and Spain.

Last year, the June parliamentary elections in Turkey ended a 13-year single-party government rule by President Erdogan’s incumbent Justice and Development Party (AKP). AKP announced new elections (held four months later) rather than build a coalition government. In between elections, AKP ceased conciliatory policy toward the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) (a policy that was blamed for the loss of nationalistic voters). Instead, the government replaced negotiations with bellicose rhetoric. This included accusing the ethnic Kurdish minority’s People’s Democratic Party (HDP) of terrorist propaganda, bombing urban districts in Kurdish regions, and harassing news media that was critical of the government. The opposition claims this was an attempt to rally nationalist sentiment and divert public attention from accusations of AKP fraud and Turkey’s poor economic performance. It appears to have been effective. As a result of the November 2015 elections, the AKP retained power by winning 49% of the vote share.

These cases and additional research detail leaders’ strategic domestic diversion decisions. Our research addresses how severe repression must be in order to divert the public’s attention and criticism away from the economy (and toward in-group cohesion and out-group threat), and on strategic responses from the minority groups.

Diversionary Conflict

Diversionary war theory generally suggests that state leaders facing low popularity or a depressed economy initiate conflict overseas to divert the public’s attention and rally support – especially when there is an upcoming election. For example, (see here, here, and here) when inflation or unemployment is high, US presidents use aggressive foreign policy to divert the public’s attention away from the underperforming economy and towards foreign policy success. Recent work argues that leaders may also demonize and repress domestic minorities as a way to divert. In two research articles (Martinez Machain & Rosenberg and Klein & Tokdemir), we explore the strategic interactions between leaders with diversionary incentives and potential target domestic minority groups. Domestic diversion is rare because there are other, more efficient ways (such as general repression or foreign conflict) to rally support. In order for domestic diversion to be an effective option for maintaining power, the minority group has to be perceived as a threat. It is not always easy to identify such a group.

The Level of Repression Applied

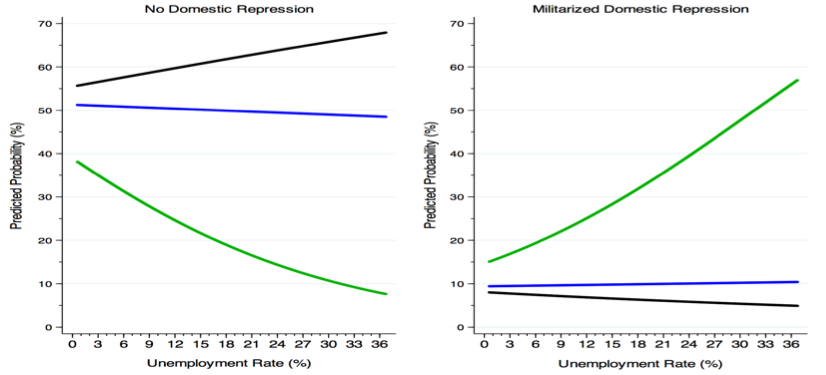

When states decide to engage in domestic diversion they must strategically select a minority group target and the severity of repression that maximizes the diversionary potential and minimizes the probability of backlash or escalation. The benefits must outweigh the costs of repressing a domestic minority. A minority group’s organization and mobilization capabilities define threat perception and, therefore, the legitimacy of targeting the minority group. Excessive repression against the wrong minority group only adds to the criticisms and failures of the leader. Our research demonstrates this strategic calculus. As shown through the graphs, as a country’s unemployment rate increases, the severity of incumbent leaders’ domestic repression is strategically calibrated in accordance with a minority group’s organizational capability. Leaders employ an ancient strategy of divide and conquer within their country by governing aggressively and “cleverly.”

Keeping Your Head Down

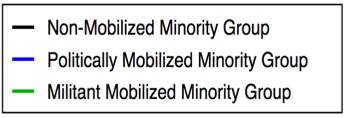

If domestic diversion is to be effective, the targeted group needs to be perceived as a threat by the population. While any minority group could technically be a potential candidate for diversion, the group’s behavior(s) will make it much easier for the government to represent it as a threat to the general population. Minority groups, and particularly group leaders, know this and adjust their behavior accordingly to avoid being targeted. Thus, we will observe members of minority groups being less likely to engage in protest and rebellion in times of economic downturn and when there are upcoming elections. The graph below shows how, surprisingly, minority groups are more likely to rebel in times of economic growth, rather than during economic decline (which increases grievances and which lowers opportunity costs of rebelling) contrasting previous expectations. We find that the predicted probability of a minority group rebelling during a non-election year is 26%; in election years, this drops significantly to 21% (previous research finds that elections can be focal points for protest and rebellion).

Putting it All Together

Our research suggests that in election years, if the economy is weak, minorities face an increased threat of non-lethal repression (for example, violent government responses to protests, torture, and/or forced resettlement). But, because potentially targeted minority groups recognize the threat of domestic diversion, we may see less political activism by organizations that fear being targeted, which is also a common behavior country leaders practice to avoid diversionary conflict with others. This in turn reduces leaders’ ability to exploit in-group – out-group apprehensions and tensions, thereby limiting leaders’ opportunity for domestic diversion. Our research suggests that both leaders and targets of violence, i.e. minority groups, act strategically towards each other in the presence of poor domestic conditions.

Graig R. Klein is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Security Studies at New Jersey City University. Carla Martinez Machain is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Kansas State University. Efe Tokdemir is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Binghamton University.