By Kyleanne Hunter for Denver Dialogues.

Introduction by Deborah Avant

In an earlier post, Sarah Bakhtiari wrote of a role for the warrior scholar. Indeed, soldier-scholars are in a unique position to bridge the gap between the academic and policy worlds. Today we have another in an informal series of posts from soldier-scholars. Kyleanne Hunter, today’s contributor and a “veteran-scholar,” directs our attention towards another kind of gap – between civilians and the military. The latest manifestation of this gap in the United States revolves around how we speak about military strength. It is one that prospective Commanders-in-Chief – as well as scholars, civilians, and military leaders – should attend to.

By Kyleanne Hunter.

Mind the Language Gap on Military “Strength”

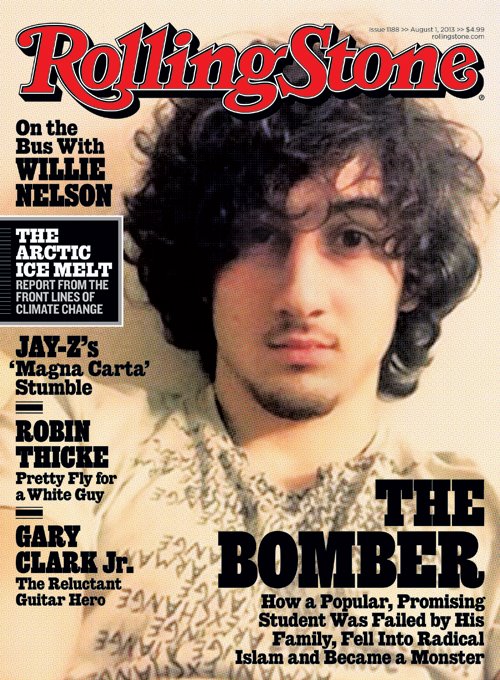

Earlier this year Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump said the following:

There was initial backlash to this statement given the perception that Trump was implying veterans suffering from PTSD were “weak.” I don’t know if that was his intent (a veteran in the room said the way his words were taken out of context was “sickening”). Regardless, the controversy reveals a gap between what civilians say and what members of the military hear; a gap with potential for deadly consequences. Namely, we need a new way to talk about “strength,” “weakness,” and military mental health.

With the dawn of the all-volunteer force in 1975, Morris Janowitz expected that the military would grow less and less representative of – and represented in – the society it was charged to protect. Over 20 years later, then Secretary of Defense William Cohen saw these effects, stating that “a chasm…is developing between the military and civilian worlds.” The controversy over Trump’s remark highlights how this gap continues to evolve. Differences between civilians and the military in demographics, politics, and culture mean that civilians may not always be aware of how their words are interpreted.

There is a particular charge associated with strength. Strength – physical and mental – plays a central role in training and is key to military identity. I witnessed this first hand when going through Marine Corps Officer Candidate School. Part of this identity is rooted in functionality. Physical capability and mental stamina are both essential for combat operations. In the proverbial foxhole, you must be confident that your fellow soldiers are competent and capable of handling the hard realities of war. It is why recruits train relentlessly, why combat units hold high physical standards, and why physical weaknesses are dealt with swiftly. But strength is more than functional – it is a touchstone of identity. In Ricks’ words, “Marines possess a repulsion towards the physical unfitness of civilians.”

Strength has become a way of setting military personnel apart as capable of performing feats others cannot. And it is more than just physical. Success in combat requires individuals to suppress emotion. As Karl Marlantes asserts in What It Is Like to Go to War, combat depends on a type of strength unparalleled in the civilian world. A soldier has to be able to “engage in acts of violence requiring physical perseverance,” all while simultaneously “dehumanizing the enemy” and suppressing the feelings of mourning for his friends. The result is a “shell-shocked” stoicism masked as strength experienced by combat soldiers, a suppression of emotion for self-preservation.

What Does Strength Entail After Combat?

The strength that allows one to be successful in combat has real and lasting mental and psychological impacts on service members. The acts one must undertake during war often result in conduct that would otherwise be a violation of one’s moral compass or personal ethics. It is thus not just the experience of trauma that results in members of the military experiencing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), but recognition of the horrors performed during war.

The long-term impact of these “soul wounds” is undeniable. Suicide has eclipsed combat as a killer of both active duty and veteran troops. Short of suicide, moral injury and related mental health has been cited as a leading cause of veteran shame and isolation, as it leads to a feeling of weakness inconsistent with the military identity of strength. Survey data and analysis from both 2004 and 2015 show that there has been little to no change in the perceptions of the stigma of being perceived as “weak” for seeking mental health care after a combat experience. Interestingly, digging deeper into the data, one finds that a military member’s fear of stigmatization comes primarily from how civilians will perceive them. While the military has done much to change the internal perception of receiving care, there is still enough concern with being seen as weak that less than half of veterans self-identifying as needing care receive it.

One solution is focusing on the language. Those injured in battle are not seen as weak if they get medical care – they are even valorized for their injuries. No such recognition of valor accompanies moral injury. We could, however, write a similar narrative in order to bring mental injuries in line with the narrative and identity of the strong solider. This would entail redefining strength so that those needing mental help in the wake of combat experiences are more likely to reach out.

Yes, we need troops who are physically strong to fight our wars, but we also need troops – and civilians – that understand the mental and emotional strength required to seek the necessary help upon returning from war. Troops need a society that is sensitive to what it has asked military members to do and willing to connect and positively engage with them to treat and ultimately heal moral injuries. Our next Commander-in-Chief needs to understand this, but so do the civilians and soldiers that elect that Commander-in-Chief. The controversy surrounding Mr. Trump’s comments made the gap obvious – now we should begin to close it.

Kyleanne Hunter is a PhD student and Research Fellow at the Sié Chéou-Kang Center for International Security and Diplomacy at the University of Denver’s Josef Korbel School of International Studies, and a former U.S. Marine Corps Cobra pilot.