By Evan Perkoski and Philip Potter for Denver Dialogues.

When militants kill civilians, media outlets often focus on the particular tactics that were employed. This is especially true when those operations are especially deadly (as is often the case with suicide bombings) or innovative (like the “underwear bomber” from 2009). Following this summer’s attack in Nice, France, for instance, observers were eager to point out the novelty of using a vehicle as a weapon. As the head of IHS Jane’s Terrorism and Insurgency Center notes, “The use of a large truck in the attack, alongside the high death toll and deliberate targeting of a large crowd at an ideologically symbolic event represents an evolution in the use of the tactic and potentially indicates a higher level of operational planning.” Others quickly noted that both al Qaeda and the Islamic State had been extolling vehicle-based attacks for quite some time. An Islamic State video from 2014 points out that “[t]here are weapons and cars available and targets ready to be hit.” al Qaeda’s Inspire Magazine extolled the same tactic – “[t]he idea is to use a pickup truck as a mowing machine, not to mow grass but mow down the enemies of Allah.”

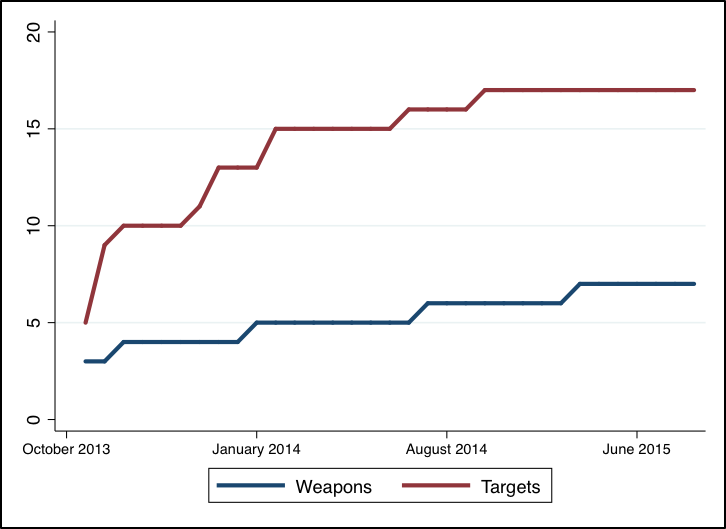

What’s often missed in these conversations is that organizations might not merely be shifting or escalating into novel tactics – they might be diversifying. And diversification has its own consequences. The Islamic State, for example, did not abandon other tactics in favor of vehicle-based attacks. Instead, their tactical repertoire merely expanded, something that’s actually been happening for some time. Relying on the most recent data from the Global Terrorism Database, Figure 1 plots the Islamic State’s growing repertoire of attacks (weapons) and targets. This demonstrates how the group’s tactical diversity has steadily grown since October 2013. They have significantly expanded both the range of their methods as well as the scope of their targets.

Figure 1

Existing research, however, has little to say about tactical diversity in militant violence, either where it comes from or its implications. That’s unfortunate because diversification poses distinct challenges for those charged with preventing attacks, establishing defenses, and structuring operations in the field. More specifically, tactical diversification introduces greater uncertainty, requiring one’s adversary to prepare for a wider range of potential operations. According to one irregular warfare intelligence analyst we spoke with:

“understanding what leads to diversification in militant tactics and violence is essential in helping to assess capability and reduce uncertainty…given that much of what we care about in an insurgent context is not directly observable, visible indicators like diversity in militant violence are critical. Successful militant groups are highly adaptable; they observe, learn, and evolve in response to environmental and/or COIN [counter insurgency] pressures through diversification. From the state perspective, highly diversified militant groups can drain scarce resources and therefore pose a more serious threat to mission objectives.”

Given the clear importance of the issue to the policy community, we thought it high time that academic work took on the question of tactical diversification. In recent research, we (along with Michael Horowitz) have tried to figure out why some militant organizations employ many tactics while others specialize in only one or a few. Drawing upon the logic of diversification in other fields – especially with regards to state militaries (particularly the nuclear triad), investment portfolios, and business firms – we argue that militants diversify their capabilities in response to external threats, both from the state and from their peers. Facing greater pressure, groups expand their tactics to demonstrate their resilience, increase their capabilities, and improve the odds of operational success. Yet there is a cost to diversification as well, which explains why not all groups go this route. Expanding to new tactics can distract a group from what it already does well, leading to failed missions and either killed or captured operatives. Only when pressure mounts are the risks worth the rewards.

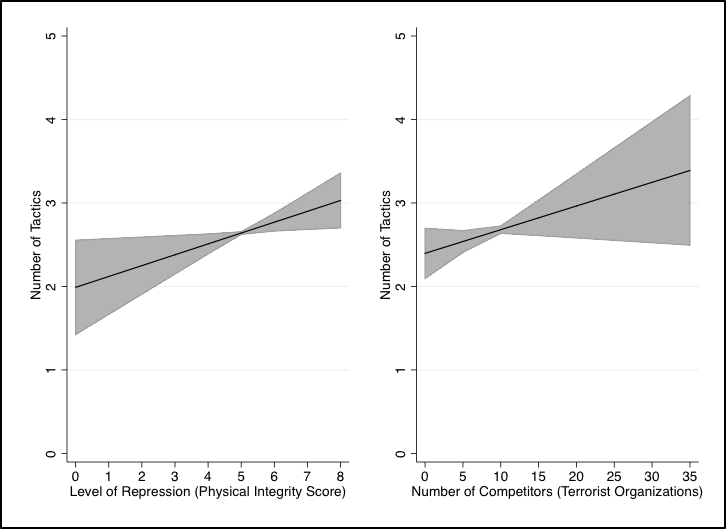

Ultimately, we find strong evidence that competitive pressures drive militants to diversify their tactical portfolios. Examining the attack patterns of militant groups across two data sets, the Global Terrorism Database and the Minorities at Risk Organizational Behavior (MAROB) database, we find that the level of state repression and the number of terrorist competitors are correlated with tactical diversity.

Figure 2

These findings have important policy implications. First, the findings shed light on the organizations and the environments that are likely to experience tactical diversification. Second, while we are agnostic about whether repression can ultimately defeat militants, cracking down with repressive measures does seem to be associated with greater tactical diversity in the short term. Instead of subduing militants, violence might beget more violence as militants seek to strike back through more varied and potentially more effective means. Consequently, states should anticipate this and simultaneously bolster their defensive efforts as they go on the offensive.

Our research also sheds light on the strategic trajectory of groups like the Islamic State and the inherent difficulties of defending against organizations that employ a wide array of tactics. As a recent Europol report notes, “In selecting what to attack, where, when and how, IS shows its capacity to strike at will, at any time and at almost any chosen target.” It later notes that, “The wide range of possible targets in combination with an opportunistic approach of locally based groups creates a huge variety of possible scenarios for future terrorist events.” When confronting a capable, well-funded organization flush with recruits, states must expect the potential for groups to mutate and evolve as they apply pressure. Rather than backing down, groups like the Islamic State are likely to strike back and broaden the range of attacks, finding and exploiting gaps in their adversary’s defenses. Maintaining defensive flexibility – and anticipating attack creativity – is therefore crucial for success.

Evan Perkoski is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Sié-Chéou Kang Center for International Security and Diplomacy at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver. Philip Potter is an Associate Professor in the Department of Politics and the Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy at the University of Virginia.

1 comment