Guest post by Christopher J. Fariss and Kristine Eck.

Data on crime, sexual assault, and rape from Sweden continue to provoke political debates about trends and the relationship between these events and newly arriving immigrants and asylum seekers. International and Swedish commentators have politicized the collection and production of crime statistics in Sweden by using them to support claims that new refugees disproportionately engage in violent crime.

The evidence does not support the political arguments made by these commentators. We have addressed similar issues in two articles. In our Washington Post article we stated that:

In Sweden, the legal definition of sexual assault is much broader than it is in the U.S. and even other European countries. While the rate of rape has remained steady in Sweden over the past decade, changes to the legal definition of sexual assault in 2005 and 2013 resulted in increases in reported sexual assault — because more acts now fall within the legal definition and are therefore officially counted. Thus, the standard of accountability has increased.

There are two types of criminal acts that we discuss in particular in this passage: rape (“våldtäkt”) and sex offences (“sexualbrott”). The definition of sex offences is a broad category that includes everything from indecent exposure to rape. These two categories of crimes are often conflated in the discussion on sex crime in Sweden. This is important – not just because of the differing degrees of seriousness between the categories – but because the government has reformed the law on sex offenses in 2005 and 2013 to widen its coverage. This means that the government is now counting a larger set of events that now legally constitute sex offenses than it did before.

Taking the reported event numbers at face value and inferring a trend is challenging because of this changing standard of accountability. As we have argued elsewhere, changes to the law in Sweden have likely encouraged victims to come forward with their allegations of sexual abuse. As victims are increasingly likely to report abusive events to the authorities, it becomes difficult to determine if it is the “true” number of events that has changed or if it is just the level of reporting that has changed. The existing data do not allow us to account for both processes.

The data in Sweden also cover different types of events

There are two primary sources of data for rape in Sweden: the Swedish Crime Survey (NTU) and police reports. In our previous articles, we make use of police reports because they provide us with data on rape, which is the most severe form of sexual offense under Swedish law. The Swedish Crime Survey, on the other hand, focuses on the broader category of sexual offenses without specifying which sexual offense events are rapes and which are allegations of other criminal acts.

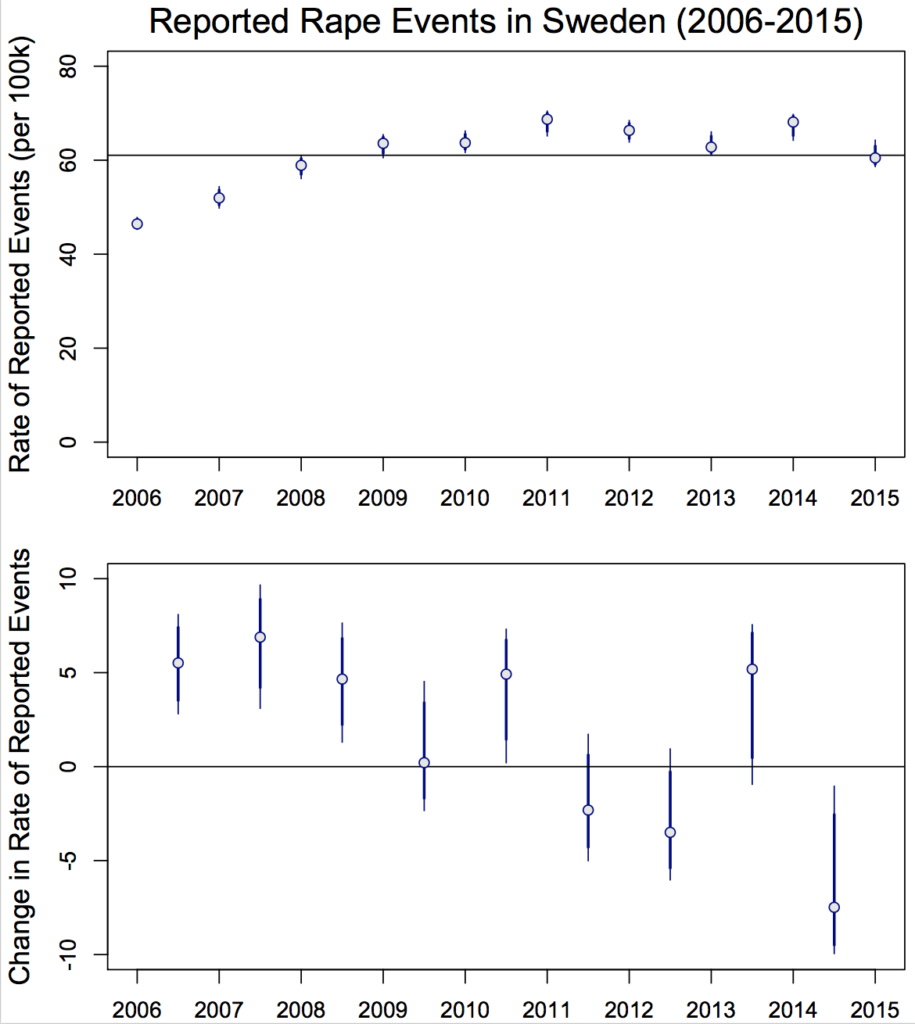

When we consider data from police reports, the reported rate of rape has remained steady over the past nine years. In 2009, there were 5937 reported rapes, or 64 reported rapes per 100k people. In 2015, there were 5918 reported rapes, or 60 reported rapes per 100k people. However, there was an increase in the reported number of rapes immediately after the change in the 2005 law. The Figure below shows the trend in reported rapes per 100k people in Sweden from 2006-2015 and the change in the reported rape for the same period.

In the past nine years, the reported rate of rape has remained steady at approximately 64 reported rapes per 100k people in Sweden.

Why not also include data from the National Crime Survey (NTU)?

Many people responded to our articles by citing data from the National Crime Survey (NTU) on an increase from 1% to 1.7% in sexual assault. In doing so, they misunderstood the important distinction between sexual offense and rape.

While the NTU survey includes a question about rape, it has not released the raw data or discussed the findings. There are two likely reasons for this. First, there are so few cases of rape in the survey data that they cannot confidently make estimates about its occurrence in the population. Second, the authors of the report believe that respondents’ perceptions may not be accurate reflections of the legal distinctions between various categories of sex offenses.

While the NTU is not confident in making precise estimates of the occurrence of rape, it does believe the data are sufficient to conclude that the rate of rape and other forms of coercive sexual offenses (“sexuellt tvång”) is higher than data from the police reports indicate. This means that there is underreporting by victims. Unfortunately, we cannot estimate how the probability of a victim reporting a sexual offense event has changed from year to year, and this affects our ability to draw conclusions about trends in the rape data.

Rape is a problem in Sweden…because it still occurs

As long as any rape occurs in Sweden, it will constitute a social ill. As long as perpetrators are not punished, the need exists to improve the laws and institutional procedures which regulate what constitutes consent and what is – and is not – permissible sexual contact. This process is still ongoing in Sweden, where the government’s Committee on Sex Crimes recently released a report recommending further changes to the law.

But in addressing rape and other forms of sex offense, it is important that policymakers and citizens have a clear picture of cause and effect when considering observable patterns in the data. Our argument is that no data exists to suggest that an increase in reported rape has occurred over the past nine years, nor any reason to believe that there is a relationship between recent immigration influxes and rates of rape. We object to analyses which do not take into consideration what the different sources of sexual offense data include, how these data were collected and aggregated, and why the event counts might change over time for reasons relating to the methods researchers used to produce the information in the first place. Discussing how data are collected may seem pedantic or uninteresting, but when commentators wish to use this information to make claims about how individuals in communities commit acts of violence upon each other, it is essential that they take into account what the data can – and cannot tell – us.

Kristine Eck is an associate professor in the department of peace and conflict research at Uppsala University. Christopher J. Fariss is an assistant professor in the department of political science and faculty associate in the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan.

The full NTU report (in Swedish) can be found here. The discussion on rape is on p.51,52: https://www.bra.se/download/18.37179ae158196cb172d6047/1483969937948/2017_1_Nationella_trygghetsundersokningen_2016.pdf

*Note: this piece was originally posted on April 7th but was rescheduled in light of a terror attack in Stockholm.