By Graig R. Klein & Patrick M. Regan

The recent protests in Iran are the bubbling over of economic and political grievances ranging from increased food prices, inflation, political corruption, and even Iran’s foreign policy. Many of these causes are unsurprising; revolutionaries, activists, journalists, and scholars alike have shown us so. What we are less certain about is how governments react to protests, when accommodation or coercion is more likely, and under what conditions protests could be more or less effective in changing the status quo.

Our research (forthcoming in International Organization (IO), data available here, codebook available here) takes a systematic approach in helping us understand how and why governments respond to protests. The combination of protest characteristics, protesters’ tactics, and protest history creates two distinguishable cost parameters–concession costs and disruption costs–that influence the government’s response. We examine the recent protests in Iran to demonstrate some generalizable patterns of how changes in these costs changed Iran’s response which escalated from arrests, to beating, to shooting, to killing, and then moderated to crowd dispersal.

We of course are not the first to analyze protest-response dynamics. Others’ research demonstrates that non-violent campaigns are more likely to lead to negotiation rather than coercion by the state. When protesters have demands that require significant political redistribution or expressed through violence, governments are more likely to respond with violence and resist accommodation.

What are Concession Costs?

Concession costs are the political costs protesters create and are a function of protesters’ demand(s), the use of violence and demand history. Demands range from what could be easy-fixes by the government (i.e. a salary demand by government workers) to demands that seek to overhaul the political system and threaten political survival (i.e. the demand of a resignation of a political leader). When demands are recurring or violent, it increases the threat to the government. Concession costs range from 1 to 5. A high concession cost protest can be defined as recurring political process demands expressed through violence. A low concession cost protest can be a non-violent demonstration against land reform.

What are Disruption Costs?

Protest location, duration, and size define disruption costs and approximate public disorder and the loss of economic activities caused by protests. As any one of these components increase, security, markets, and public life are inhibited. Disruption costs range from 1 to 9. High disruption cost can be defined as a 3-day protest with 12,000 participants in the capital. A low disruption cost protest can be 1-day with 75 participants in a major city.

The Effect of Costs on Government Response

Using the Mass Mobilization Data Project, we generated concession and disruption costs for 10,133 protest events in 161 countries from 1990-2014 and analyzed the governments’ responses of disregard, accommodate, coercion (beat, shoot, or kill), and crowd control (crowd dispersal & arrests).

When one cost is high the other can be low or both can be high, etc. The combination of costs affects the government’s decision.

Higher concession costs increase coercion. When concession costs are high, the government coerces 29% of the time and when they are low, 2.5% of the time; accommodation increases from 2.5% to 11% of the time when concession costs shift from high to low.

Higher disruption costs increase accommodation. When disruption costs are low, the government accommodates 3% of the time and when they are high, 17% of the time; coercion remains consistent at 10% of the time.

Low concession and disruption costs leads to governments disregarding the protest 75% of the time. Combined high costs make coercion more likely than accommodation. When both are high, the government coerces 34% of the time and accommodates 6% of the time.

Can we apply these general results to contemporary conditions in Iran to develop expectations about the government’s response?

Iran Protests

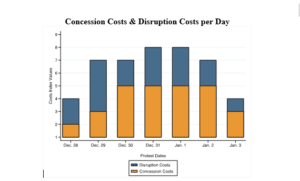

Following the Mass Mobilization Data Project coding rules, we coded daily protest concession and disruption costs (illustrated below) from December 28th, 2017 – January 3rd, 2018. The concession costs quickly reached the maximum value, remained high for several days, and decreased on the seventh day. The disruption costs started low, quickly escalated, and then just as quickly decreased. Iran’s response varied in accordance. Harsh suppression was not the immediate response, changes in the costs parameters motivated escalation and then de-escalation in Iran’s response.

As expected from our research, the initial response on December 28th when both the concession and disruption costs were relatively low, Iran responded with its normal response to protests over the past 25 years–arrests. On the second day when both costs increased, we observed an escalation in Iran’s response to include both arrests and beatings. By day 3, concession costs reached the maximum value because there were consistent reports of protesters’ demanding the resignation of both Ayatollah Khamenei and President Rouhani. As expected, because protesters’ demands challenged political survival, Iran shot protesters. From December 31–January 2, as concession costs remained at the maximum and disruption costs remained significant, Iran’s response escalated to include killing protesters. But on January 3, when both costs decreased, Iran returned to a response of crowd dispersal.

If more protests erupt, the protesters can manipulate the internal tension within the Iranian government by changing the concession and disruption costs. Our evidence suggests that Iran is more likely to accommodate at least some of the economic and political grievances if the demands about political change are tempered, moving away from resignations and to political openings. Moderating the concession costs could also reduce deadly coercion.

However, if the protests restart and the demands are resolute, our research suggests that we could expect Iran to crack down harder on the protesters, as they did in 2009.