Guest post by Avery Reyna and Salah Ben Hammou

On May 17, the Malian government released a televised statement claiming that soldiers attempted to stage a coup against Interim President Assimi Goïta on the evening of May 11–12. The statement provided few details, simply claiming that the perpetrators were “anti-progressive” soldiers backed by a Western state to “break the revolution.” Ten individuals were allegedly detained, including Colonel Amadou Keita, an officer close to the ruling junta. Security measures in the capital, Bamako, were increased.

Observers were skeptical. They pointed to the vague nature of the allegations and a lack of troop movement on the evening of May 11. A French diplomatic source claims that the allegations serve as little more than a pretext to antagonize the French government (as the implied Western state). Others claim that the allegations help Goïta to consolidate his authority in the face of rising dissatisfaction in the military.

Ambiguities aside, CoupCast’s political forecasts for this past May reveal that Mali faced a significant coup risk. CoupCast relies on machine learning and information on historical legacies and contemporary developments to generate monthly estimates of a coup in every country. The type of information fed into the model comes from well-established findings in coup research. For instance, coups are more likely in countries with historical legacies of coup attempts, those experiencing periods of economic downturn and food instability, and those headed by military governments or fledgling democracies.

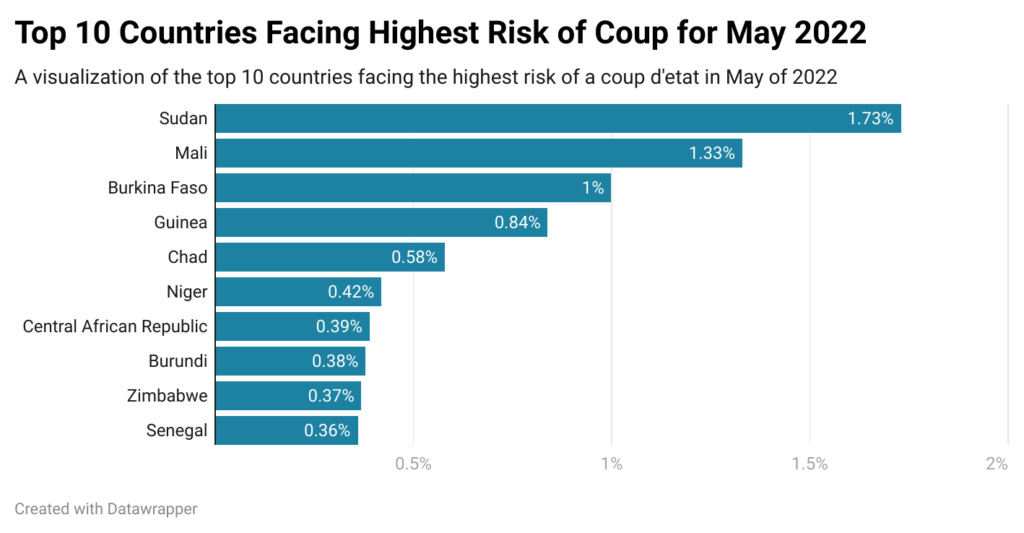

Based on these features, last month’s estimates (shown below) suggest it is unsurprising that a coup attempt would have occurred in Mali. The West African country ranked second only to Sudan as the world’s most at-risk country.

Just last year, Mali experienced a successful coup that resulted in Colonel Goita coming to power. Only nine months before that, Malian soldiers removed President Ibrahim Keïta. Military interventions have consistently occurred in Mali, which has experienced around 8 coup attempts since independence in 1960. These events have served both as catalysts for democratization (March 1991’s coup) and as its foil (March 2012’s coup).

CoupCast also considers ongoing armed conflicts and economic conditions when determining coup risk—both big challenges in Mali. The Malian government has been combatting a jihadist insurgency for more than 10 years. Last May’s coup worsened the struggle with rebel forces, who have perpetrated recent attacks against UN peacekeepers and Red Cross employees across the Sahel. Mali’s economy is also hurting. The 2020 recession led to stagnating per capita GDP, which is projected to increase poverty throughout this year. Growth since 2021 has been mainly caused by a rebound in consumption, an expansion of growing inflationary pressures, and a worsening hunger crisis across the continent. This crisis has been compounded by COVID-19 and by the surging food prices due to the war in Ukraine.

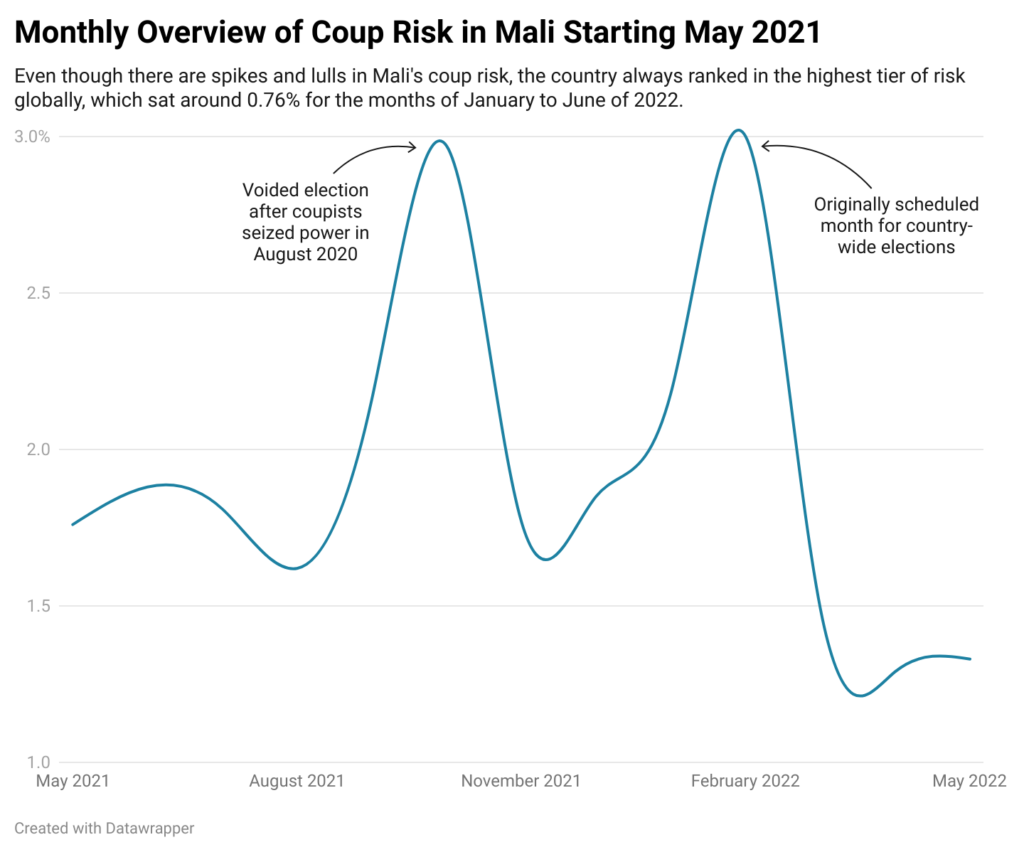

While Mali faces a high coup risk relative to the rest of the world, its overall risk has fluctuated since last year’s power-grab, shown below. October and February’s peaks are likely driven by CoupCast’s sensitivity to election dates. This is relevant given that both scheduled elections in October and February were directly voided as the result of previous coups. After Keïta’s downfall in August 2020, the coupists announced a two-year transition, effectively voiding the original October 2021 election. However, the May 2021 coup reset the transitional process, voiding the election scheduled for February 2022. The country’s next elections are scheduled to be held in 2026.

The trail of coups has taken a toll on Mali’s foreign relations. Since the 2021 coup, the ruling junta has faced backlash from France and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) over the power grab and proposed 5-year transition to civilian rule. France is set to leave its defense agreement with Mali, which served to assist against the insurgency, by summer’s end. The decision was made partly because of concerns over free speech and other freedoms in Mali following the coup leaders’ decision to indefinitely suspend Radio France International (RFI) and France24. Similarly, ECOWAS has imposed a trade embargo and sanctions on Mali in response to the junta’s delaying of elections, a strategy used against other coup-inflicted states such as Guinea and Burkina Faso. Though designed to put pressure on the junta to hold elections, these measures may inadvertently spark a counter-coup by rival factions in the military.

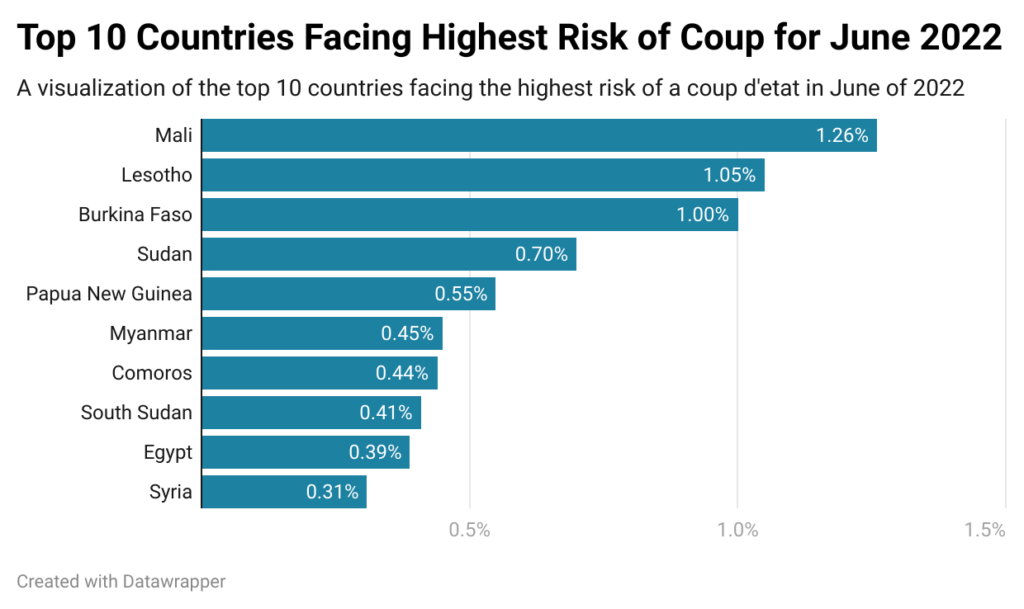

Presently, Mali’s coup-ripe conditions show no sign of subsiding as we move through June, as the preliminary estimate shows below. Despite its slight dip in overall coup risk from May, Mali is estimated to be the world’s most at-risk country this month. Whether an actual coup will occur remains to be seen, but observers would do well to keep their eyes open.

Avery Reyna is a Social Sciences Undergraduate Student at the University of Central Florida. Salah Ben Hammou is a Security Studies Ph.D. Student at the University of Central Florida.