Guest post by Johannes Karreth and Jaroslav Tir.

At the recent Kuwait International Conference on Reconstruction of Iraq, countries and international organizations pledged US$30 billion to reconstruct Iraq after years of war, falling well short of the US$80 billion estimated necessary by the Iraqi government. As this case aptly demonstrates, civil wars create lasting damage that can take decades to overcome. Despite such huge costs, the international community struggles to find effective ways to prevent conflict escalation, relegating their involvement to the post-conflict reconstruction phase. But might there be ways to address conflicts before they erupt into all out war?

In a new book, we present evidence for an optimistic view of how the international community can help prevent civil wars. We focus on a specific subset of intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) with the capacity and self-interest to engage in member states in a way that directly addresses commitment problems in pre-civil war bargaining. These highly structured IGOs include institutions such as the World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, and the Economic Community of West African States. As multilateral bodies, these organizations have clearly defined – and often economic – mandates. While mediating political disputes lies beyond their purview, civil wars in member countries impede these organizations’ ability to carry out their tasks. Such functional self-interest gives strong incentives to avoid political violence in member countries.

The leverage of highly structured IGOs in member countries has a notable influence on the costs and benefits that governments and rebels face in early phases of political unrest and violence. When highly structured IGOs are engaged in a country, both governments and rebels can expect clear costs from escalating violence: it will lead to a disengagement of these IGOs and withdrawal of their staff, resources, and other benefits. Yet, highly structured IGOs also carry the promise of rewards for keeping the peace by providing substantial resources and benefits conditional on the absence of further violence.

This puts highly structured IGOs in a unique position to credibly condition benefits on conflict prevention. Their self-interest in successful institutional performance requires that they avoid engagement in contexts of high fragility and violence. This means that when highly structured IGOs are engaged in a country, governments and rebels in pre-civil war bargaining are acutely aware of the high material costs of violence. In turn, this provides a crucial commitment device to settle conflicts before they escalate.

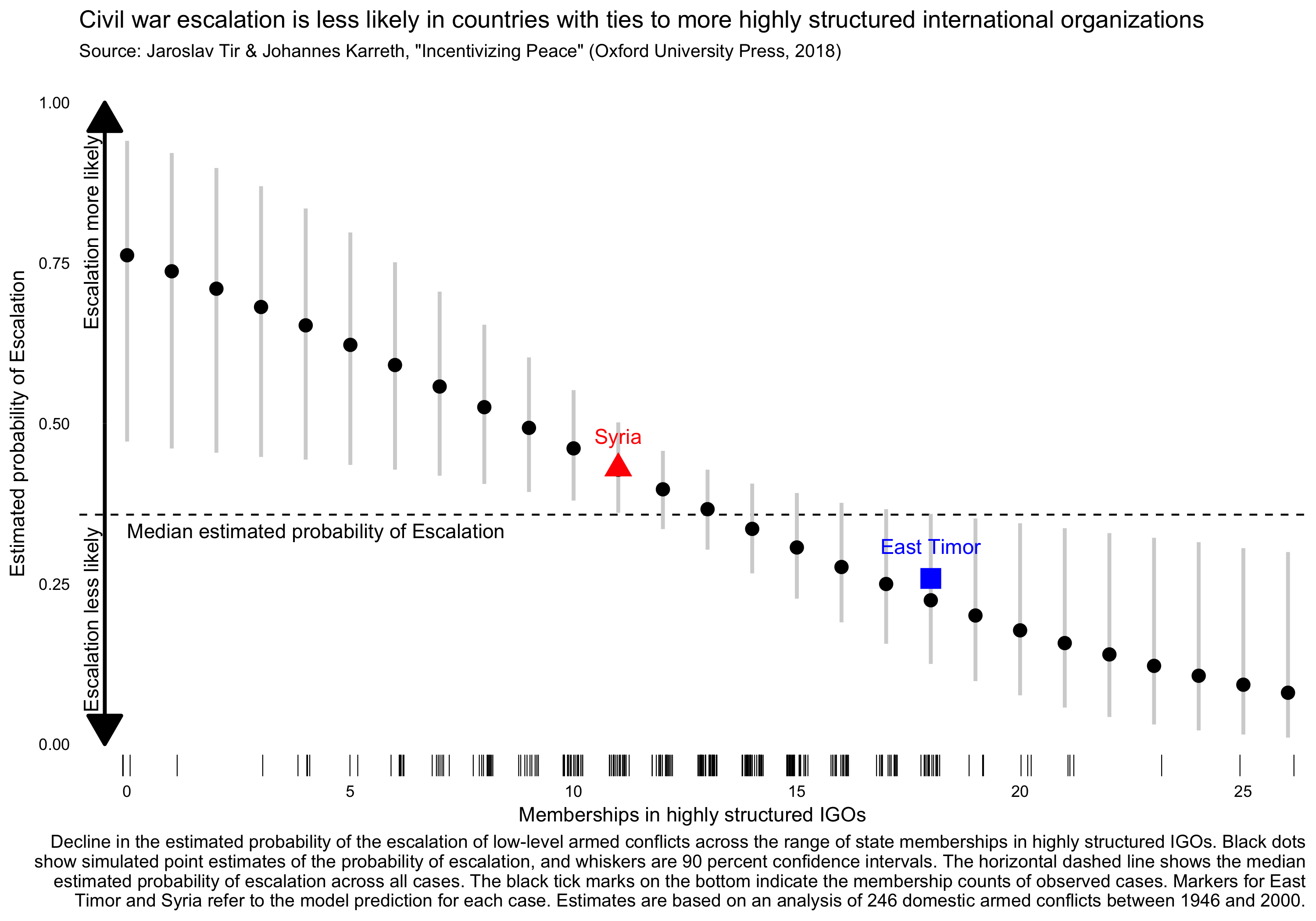

The evidence suggests that the engagement of highly structured IGOs in member countries is associated with a substantial decline in the risk that political conflicts escalate into civil wars. Since World War II, roughly one-third of more than 260 separate low-level armed conflicts have escalated to civil war. But conflicts in countries with more connections to highly structured IGOs faced a considerably lower risk of escalation, reduced by up to one half. The figure below, created based on our statistical analysis, highlights this pattern.

Representative of these broader trends, the history of East Timor illustrates how international organizations can successfully incentivize conflict parties to negotiate and resolve political disputes before they escalate. In Indonesia, a crisis originated when the East Timorese opposition demanded independence in the late 1990s. After an initially violent response by the Indonesian government, highly structured IGOs – most notably the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank – threatened and imposed sanctions on the regime. The regime responded by yielding to the pressure of calls for East Timor’s independence. In the end, both sides reached a settlement and avoided full-scale civil war. As promised, highly structured IGOs then resumed their activity in the respective countries. Both Indonesia and East Timor have since made notable economic improvements, partially helped by resources coming from the IMF and World Bank.

As a counterexample, highly structured IGOs did not have much leverage to set similar incentives for the conflict parties in Syria in 2011. In this case, the Syrian government was comparatively isolated from the international community, including highly structured IGOs. Without their leverage, there was little the international community could do to effectively curtail the government’s response to the opposition. Instead, the regime went on a major offensive. Seeing this, the opposition turned to defending itself and grew into a rebel force. Without the requisite leverage to resolve commitment problems, other international efforts at mediation have failed.

Highly structured IGOs have increasingly emphasized concerns about the detrimental impact of violence on their missions, as the examples of the World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, and the Economic Community of West African States show. Studying the role of highly structured IGOs and the incentives they bring to political disputes in member states suggests one way in which international organizations can help limit the dramatic costs of civil war. Coordinating these efforts may provide the international community with an effective conflict resolution tool moving forward.

Johannes Karreth is Assistant Professor of Politics and International Relations at Ursinus College. Jaroslav Tir is Professor of Political Science at the University of Colorado Boulder. Their book – “Incentivizing Peace: How International Organizations Can Help Prevent Civil Wars in Member Countries” – is available from Oxford University Press.