By guest contributor Salah Ben Hammou

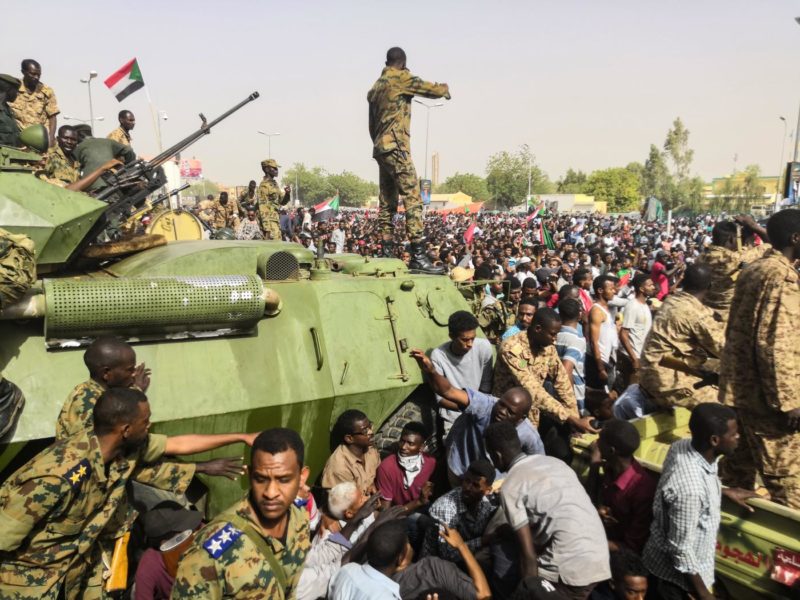

On April 11, 2019, the Sudanese military ousted President Omar Al-Bashir in a coup d’etat. Wanted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity and genocide in the Darfur region, Al-Bashir faced months-long protests for political and economic reform. The coup signaled the military’s withdrawal of support for Al-Bashir, who himself took power in a military coup in 1989.

Protestors’ reactions turned sour when the armed forces established the Transitional Military Council (TMC), comprised of officers from the national military as well as the paramilitary organization, Rapid Support Force. The TMC declared that it would oversee a two-year transition before returning power to civilians. Citizens viewed the move as a power-grab by old regime insiders and demanded civilian rule. Tensions culminated in a sit-in at a military compound in Khartoum, which saw a brutal backlash from security forces and left more than 100 people dead.

Domestic and international pressures led the TMC to establish the Sovereignty Council, comprised of six civilians and five military officials designated to oversee Sudan’s transition to democracy. The agreement presented civilians as the transition’s leaders but maintained the security forces’ influence in politics. A year since the coup, the Sudanese security forces appear as powerful as ever, as evidenced in their meetings with foreign leaders, sustained economic privileges, and evasion of justice for the Khartoum massacre.

How does the security forces’ involvement in politics influence prospects for democracy in Sudan?

Civilian control over security forces and the military’s abstinence from political power are generally seen as necessary ingredients for a robust democracy. As noted by previous commentators, research shows that when military officers hold political power, they are more likely to engage in state repression and belligerent foreign policy than civilian governments, while also facing a greater risk of future coups. My own research investigates the relationship between the military’s involvement in politics and government spending and shows that, unsurprisingly, militarized governments generally prioritize defense spending over spending on health and education.

Sudan’s democratic prospects appear grim when considering these trends. After all, top security and military officials such as General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo remain highly influential on the Sovereignty Council as chair and deputy chair respectively. Security forces have also gone unpunished for the massacre at the Khartoum sit-in, have safeguarded their own budgetary affairs from civilian intervention, and bypassed civilian permission to hold impromptu meetings with foreign leaders.

A look at similar power transitions around the world, however, shows that sustained military power—at least in the short-term—may actually improve prospects for stability, and even for democracy. It’s not unusual, in transitions from dictatorship to democracy, for the prerogatives of overthrown elites to be maintained. Former elites may even be quietly supportive of a new government if their physical or material wellbeing is guaranteed and they have a stake in the new regime. This support is especially important in countries with a legacy of military rule, because, as research shows, transitions from military rule are about 50 percent more likely to fail than other democratic transitions, and new democracies face a higher risk of military coups than civilian dictatorships. This risk significantly decreases when military spending increases and prerogatives are given.

In other words: “rewarding bad behavior” can help strengthen new regimes. The Chilean democratic transition saw former strongman Augusto Pinochet appointed as the military’s commander in chief, and the security forces maintained hefty salaries and off-budget funding. Soldiers also enjoyed immunity from human rights abuses committed during Pinochet’s regime. In Brazil, top-ranking officers held presidential cabinet positions throughout the transition and preserved some autonomy over their affairs. Both transitions progressed without overt contestation from security forces. Argentina’s transition was different—when civilians sought justice for human rights violations committed during the previous regime, the army mutinied (more than once). Egypt’s democratically elected president Mohamed Morsi purged senior officers upon taking power and sought to curb the military’s involvement more broadly, which led to his ouster a year and a half later.

These trends suggest that tolerating some degree of influence from Sudan’s generals and commanders is essential for stability—at least in the short term. The pro-Bashir mutiny in January shows that civil-military tensions remain. Civilians should play their cards wisely. “Taming security forces” is likely to be a long-term process.

Moving to civilian control will require negotiation. In Chile and Brazil, civilian leaders negotiated with security forces to establish some degree of civilian control. In Chile, initiatives were introduced to remove the armed forces from internal security, and in Brazil, a civilian committee was authorized to allow some oversight on defense-related matters. Measures such as supplanting military governors with civilian governors in Sudan are a step in the right direction. But civilian leaders will have to enforce the means of civilian control, such as the constitutional mandate that civilians manage foreign policy and diplomatic relations. Foreign actors should respect these standards and refrain from engaging with Sudanese security forces without civilians’ consent. As time passes, other measures for oversight such as appointing civilians as Interior and Defense Ministers could also prove useful.

While seemingly antithetical to democratization, allowing Sudanese security forces a seat at the table and avenues of influence may help preserve the transition in the short term. However, civilians should not drag their feet in establishing means for civilian control and must perfect the art of placating security forces while also establishing the necessary institutions for democracy in Sudan.

Salah Ben Hammou is an incoming PhD student at the University of Central Florida. His research interests include civil-military relations in authoritarian regimes, and democratic transitions, specifically as these processes relate to political economies.