Guest post by Desirée Nilsson and Isak Svensson.

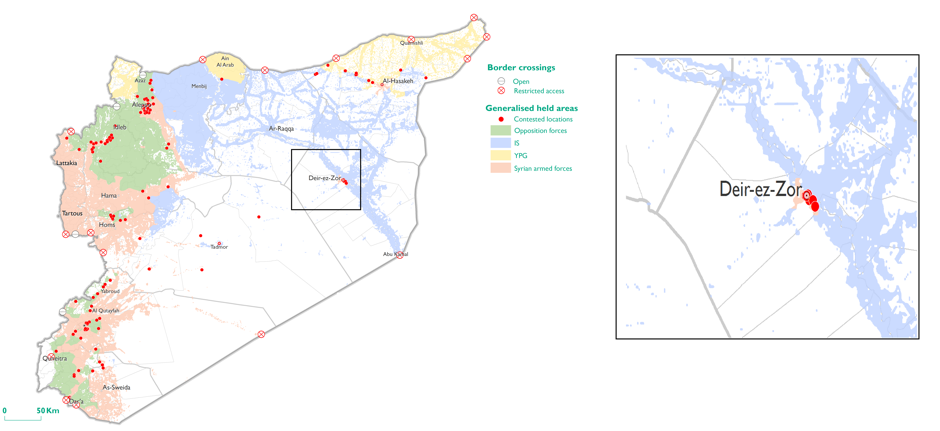

Ongoing civil wars in Syria, Mali, Afghanistan, the Philippines, Thailand, and Uganda illustrate the need to better understand religious dimensions of armed conflicts. In a recent article published in Journal of Conflict Resolution, we provide new data on religion and conflict worldwide – during the time period 1975-2015 – which can help inform our understanding of the religious dimensions of armed conflicts. Drawing on the data and findings presented in that article, we shed light on three widely held beliefs concerning religious conflicts.

Claim 1. Armed conflicts between actors from different religious identities are becoming more common

The patterns in our data suggest otherwise. The idea about an emerging Clash of Civilizations between people from different cultures and religions was formulated most vividly by Samuel P. Huntington. If we talk about conflicts in which religion serves as an identity-marker – such as in conflicts between Shia and Sunni Muslims, or Catholics and Protestants – then religious conflicts are neither decreasing nor increasing in numbers.

If we also take into account whether or not the conflict is fought over a religious issue a different trend emerges. The type of conflicts we have seen in Northern Ireland or Ivory Coast, where the parties have different religious identities but where the issue at stake is not about religion per se, are becoming less frequent over time.

The patterns further reveal that conflicts between belligerents from different religious identities only show an increase in frequency when one of the issues at stake is religion. We are not the first to note that armed conflicts do not trend in the manner predicted by Huntington, or to point out the lack of empirical evidence in support of the main tenants of the ‘Clash of Civilizations’ thesis.

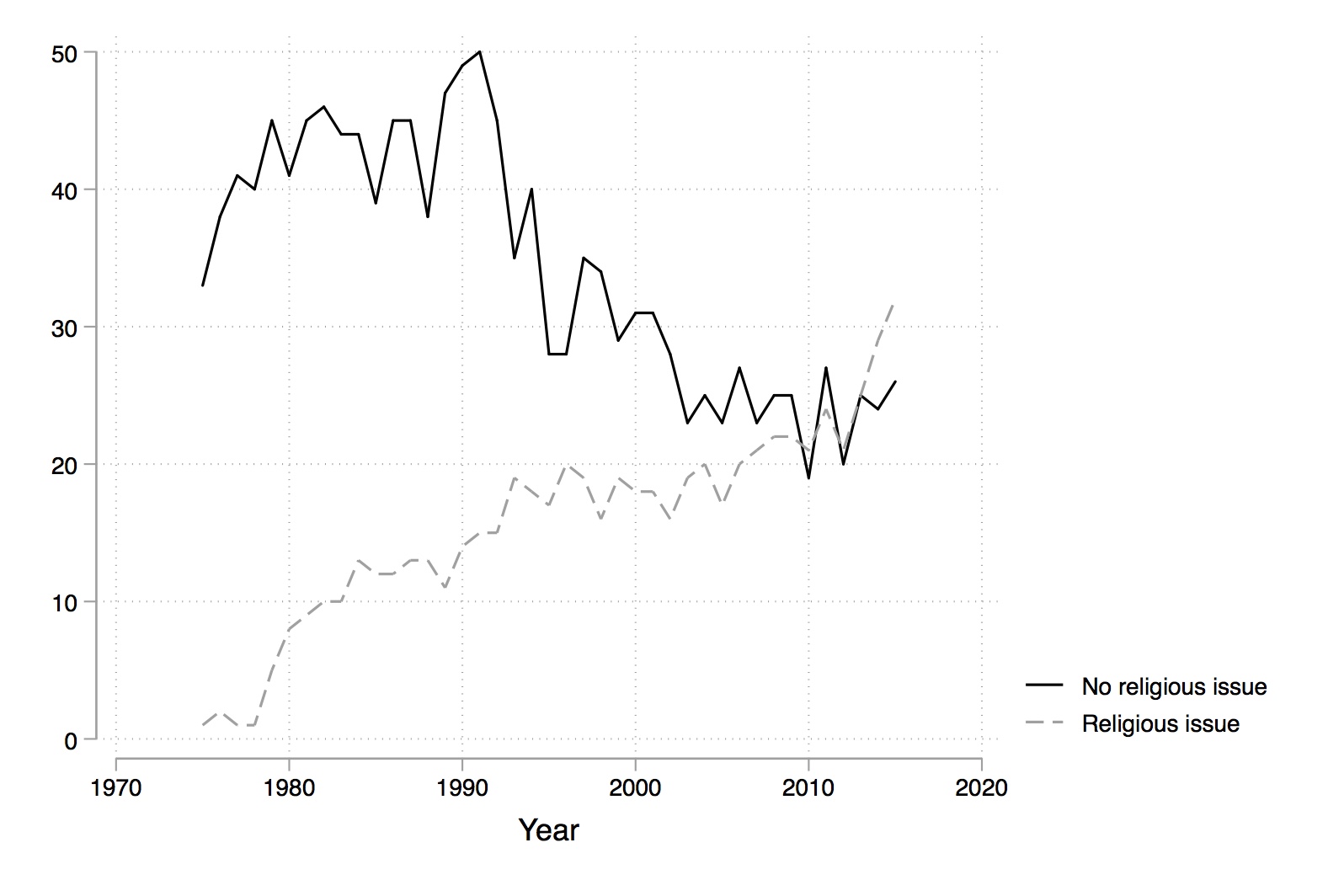

What we have witnessed, however, is that intrastate armed conflicts fought over religious issues are becoming more common in the world today. In 1975, only 3 percent of the world’s government-rebel dyads involved in armed conflict were fighting over a religious claim, whereas in 2015, that number had increased to 55 percent. Notably, this shift in the empirical landscape is manifested through two different processes: an increase in the number of armed conflicts fought over religious issues as well as a decrease in other types of conflicts.

Figure: Armed Conflicts by Religious Issue, 1975-2015: Number of conflict dyads per year

Claim 2. Islamist armed conflicts are increasing

We can discern such a trend, but only in part. If we focus on all armed conflicts where at least one of the warring actors – on the government or rebel side – had self-proclaimed Islamist aspirations at the outset of the conflict, we observe an increase in both absolute and relative terms over the last decades.

‘Islamist conflicts’, however, capture a diverse set of actors and claims. Conflicts fought over transnational Islamist claims – involving, in particular, groups associated with ISIS and al-Qaida – have been increasing for some years now, although ISIS has now lost most of its heartland territory in Iraq and Syria.

Islamist revolutionary conflicts (e.g. in Algeria involving AIS) and Islamist separatist conflicts (e.g. the Patani conflict in Thailand) – where the religious claims do not transcend borders – are not increasing in frequency. While the former have decreased somewhat over time, the latter are more or less stable over the last decade.

Claim 3. Religious claims cannot be negotiated

The basic answer to this is: we do not (yet) know.

There is ample evidence that religious dimensions may complicate conflict resolution efforts, in the sense that religious aspirations are associated with lower chances for negotiated settlement and tend to make conflicts longer as well as more intense. In general, then, conflicts fought over religious issues tend to be difficult cases.

Still, there are several examples of conflicts that have been resolved although they were originally framed as disputes over (at least partly) religious issues. Peace agreements with MILF in the Philippines and IRP in Tajikistan are two examples of comprehensive peace settlements with Islamist movements. Recent scholarly work shows evidence of both ongoing and previous mediation and negotiation attempts in Islamist conflicts in Nigeria, Egypt, Mali, and Pakistan. Whether, and how, conflicts over religious claims – Islamist claims in particular – can be resolved continues to represent an important area of inquiry.

Desirée Nilsson is an associate professor in the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University. Isak Svensson is a professor in the Department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University.

1 comment

Most of these conflicts are manufactured by outside powers using religious antagonisms as a wedge to bring about the breakdown of civil order.