Guest post by Alexander P. Noonan.

In recent weeks, much has been made of President Trump’s reluctance to pressure the Russian government to extradite Russian intelligence officials indicted for hacking the Democratic National Committee’s email server during the 2016 presidential campaign. Noting that the United States and Russia do not have an extradition treaty, National Security Advisor John Bolton labeled calls for formal extradition “pretty silly.” However, the lack of any formal treaty has not deterred Russian President Vladimir Putin from calling for the extradition of Bill Browder—an investor who helped reveal massive corruption within the Russian government—or Michael McFaul, the former ambassador to Russia. Clearly, Trump and Putin understand the formal extradition relationship between the US and Russia quite differently. So what is the state of extradition between the two countries?

Extradition is a process where persons charged with or convicted of a crime against the law of one state and found in a foreign state are returned by the latter to the former for trial or punishment. With limited exceptions, the United States grants extradition pursuant to a treaty, and the US Code (18 USC 3181) currently lists more than 100 agreements in force. While the US government does not currently consider it to be in effect, the United States once had an extradition treaty with Russia.

Though the US-Russia Extradition Treaty (1887) was typical of contemporary agreements signed by the US government, how it has been handled in subsequent decades sets it apart. For instance, it is unclear whether or not the treaty was ever formally abrogated (as provided for in Article 11)—the State Department’s Treaties in Force simply lists it as “Obsolete” and the treaty was removed from the series in 1941.

Opponents of the treaty took particular issue with the provision in Article 3, which declared attempts against the life of the head of government or members of their family to be exempt from the political offense clause. At the time of its signing, critics assailed the provision as a tool to help the Tsarist regime suppress dissidents for whom violence was the primary means of dissent against autocratic rule. For example, a mass meeting to protest the treaty before it went into effect in 1893 decried the provision as “entirely opposed to American ideals.”

If the Russian government could exploit extradition treaties to punish political opponents, contemporaries feared, so too could other foreign governments facing challenges from a violent opposition. This concern was not limited to treaties with conservative governments—indeed, nearly identical protests were raised when the United States and Great Britain opened negotiations for a new extradition treaty in the late nineteenth century.

The governments of Great Britain and Russia may not have had much in common at the time, but popular opposition to extradition treaties with each country focused on similar issues. Public figures and officials alike expressed concern that otherwise common treaty provisions could be used to punish dissenters who were beyond the reach of local authorities. While these treaties contained little that was unique, events at the time colored perception of the agreements. Rather than see them as an effort to cooperate to punish criminals, which was in the common good, contemporaries instead believed that the treaties fundamentally threatened important societal principles.

Concern that extradition treaties could pose a danger to civil liberties endured well past the 19th century. Suspicion that British extradition requests could target members of the Irish opposition endured until the mid-1980s; only then did a supplement to the extradition treaty with Great Britain curb how the political offense exception could be extended to members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army. The treaty was subjected to intense criticism, nonetheless.

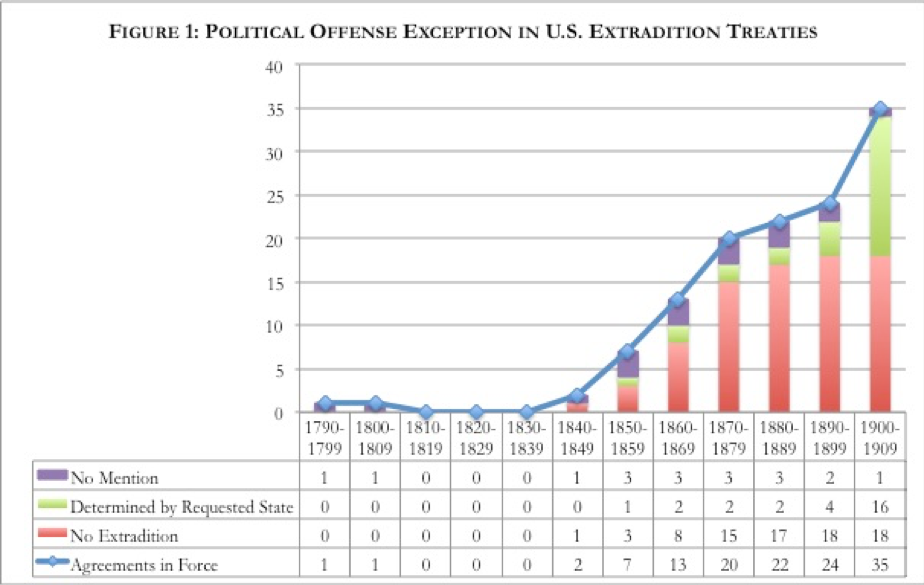

Interestingly, the proliferation of modern extradition treaties coincided with increased provisions for the protection of political offenders (see Figure 1). During the 19th century, the transportation revolution made it easier for criminals to avoid capture. Governments had to cooperate to counter the increased mobility of criminals since laws ordinarily stopped at the border. At the same time, the political offense exception reflected increasing support for individual and collective freedom as well as popular sovereignty. Uprisings—such as those across Europe in 1848—reinforced the belief that political offenders opposed autocratic regimes in the name of nationalism or self-determination. Consequently, many argued that political offenders deserved protection.

So what does this mean for the current US-Russia relationship? Extradition without a treaty is rare, but not impossible. One of the driving issues, however, is reciprocity. This is challenging when those in the country receiving an extradition request believe that the requesting country is using extradition to quash dissent. Since the 19th century, governments accounted for this concern by including provisions that allowed the requested state discretion to determine any political intent behind a request. Extradition has been—and remains—a question of rights as much as a question of law and the suppression of crime.

Alexander P. Noonan is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Boston College.