Guest post by Jesse Driscoll.

“Look, in Somalia, the cell phone system works…and it’s the only thing, maybe, that works in the country…” – Stephen Krasner, 2010

There is an ever-increasing demand for demographic data to support evidence-based policy planning. Students of James C. Scott should be attuned to the possibility, however, that systematic data collection—especially in a war zone—is an overtly political project. Relative winners and losers in a war have different incentives to cooperate with scientific data collection.

Social scientists working in active war zones know that this is not an abstract, hypothetical, or merely theoretical concern. In 2011, along with a number of colleagues at the University of California, I helped to organize and field the first representative survey of Somalia’s capital city of Mogadishu since the 1980s. The situation was grim in a way that is discouragingly familiar today: drought, displacement, and rampant corruption in intermediary institutions tasked with humanitarian reporting and relief. A defensible population estimate for humanitarian relief was the goal, and risks were mitigated by extensive outreach efforts within the Somali diaspora, flexible deployments of teams, and because we did not ask certain questions to defuse the concern that we were conducting a clan census.

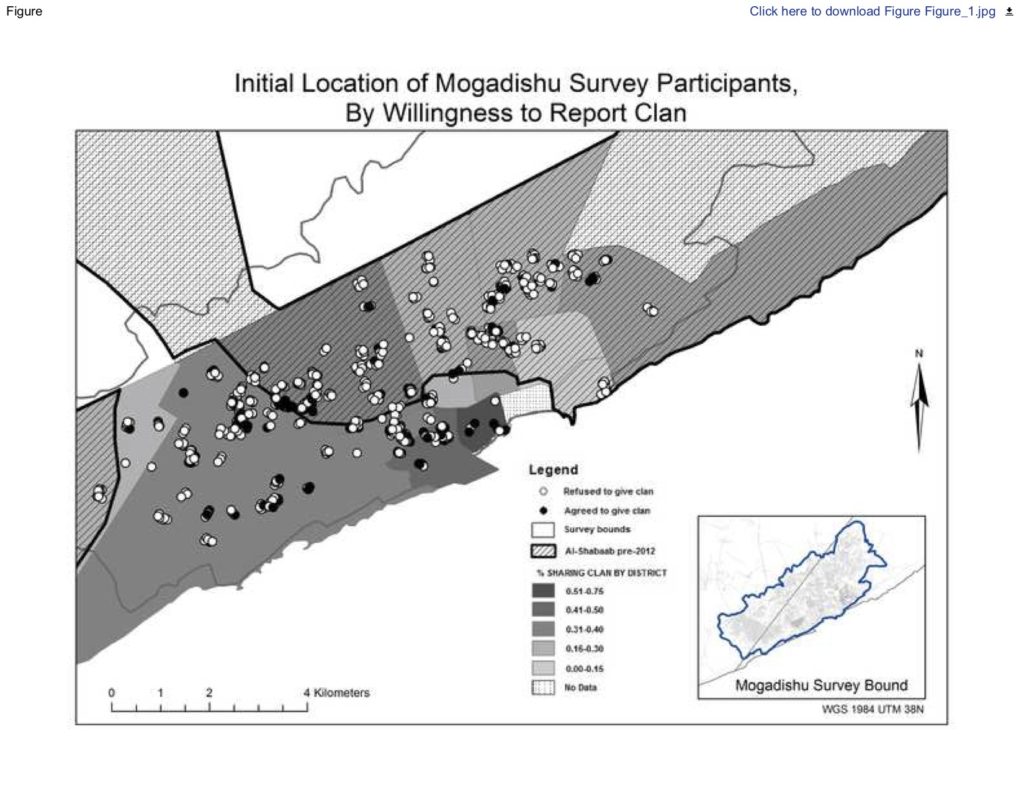

Why not ask about clan? Clan lineages have provided focal points for multiple waves of pogroms since the 1980s—nearly every time neighborhoods change hands, in fact. As Figure 1 shows, when enumerators probed respondents’ willingness to consider sharing their clan identities in a hypothetical future survey, results varied. In the commercial center, more than 70% of respondents said they would be willing to reveal their clan. In other districts, none of those surveyed said they would be willing.

The face-to-face survey revealed something else: internally-displaced Somalis living in refugee camps routinely possessed cellular telephones. We solicited cell phone numbers from respondents so that we could call them back remotely in the event that the security situation deteriorated (which, sadly, it did). We could Skype many of the same people multiple times, even years later.

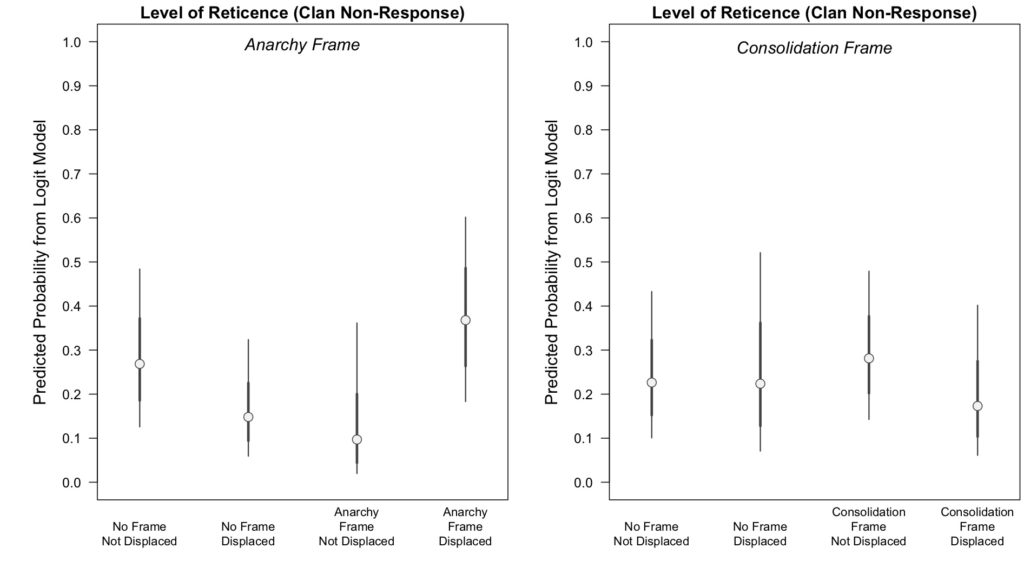

Over time, willingness and non-willingness to answer our survey questions invited psychological speculation. We focused on relative levels of fear induced by various frames of why we were conducting research. We hypothesized that respondents’ refusal to answer a question about clan identity could be reasonably assumed to be evidence of the fear. We then set out to test whether reminders of anarchic conditions, or reminders of increasingly strong central government, were more frightening to the most vulnerable residents of Mogadishu. We used randomly assigned primes to remind subjects of either anarchy or state consolidation. Then we asked whether they were willing to tell us their clan name. The rate at which each treatment group refused to answer, interacted with a measure of vulnerability, was used to make inferences about whether anarchy or centralization was a more potent source of fear.

Background security mattered a great deal. Vulnerable residents of Mogadishu were about four times less likely to tell us their clan after the anarchy prime, compared to secure residents (Figure 2). Reminders of government consolidation did not alter level of reticence at all. Results were validated with an unusual natural experiment—a car bomb, a jarring reminder of anarchy.

Our experiment produced evidence that anarchy is frightening—but haven’t we all known that since at least 1651? It is a weak source of legitimacy for the Somali government, both because there is little evidence that the state can actually protect its most vulnerable citizens and also because, even if it could, modern liberals are wary of the possibility of extortion, legitimized by “the king’s peace.”

Our discouraging conclusion, after a 5-year study, was that practically any kind of intervention that touched the lives of Somali’s most vulnerable would invite skepticism about researcher motives—and perhaps rightly so. To the extent we were neutral observers we could be accused of engaging in virtual poverty tourism. To the extent we were something other than neutral observers, however, we were aspirational partisans. One of our Somali enumerators once asked, point blank, if we were being funded by the US military to put together a predator drone list. We weren’t, of course, but his concern was valid. Some of the most productive research programs in political science over the last decade produce knowledge that is explicitly (and unapologetically) seek-and-destroy.

In a setting where famine has been used as a weapon for decades, charity cannot be seen as politically neutral. An inaugural survey of a landed population after a civil war is not a pure public good, but more akin to club goods for politically powerful social groups (who stand to benefit most from counting and will, predictably, design survey/census categories to benefit them). Residents inclined towards distrust of political centralization may wish to remain invisible.

All we can say with confidence is two things.

First, this kind of experimentation is not about to stop while ethicists navel-gaze. Cellular telephone technology was exotic just a few decades ago. Today the digital frontier is quite close. Since it is possible to recruit samples from war zones remotely, without putting oneself in harm’s way, many will do so. As such, the spread of mobile technology represents an exciting new research frontier. As the digital frontier is mapped, technology should be considered a complement to, not a substitute for, on-the-ground experience. The wisdom to not ask some questions in the first place is often hard-won.

Second, our results suggest that systematic bias lurks in datasets collected in war zones. Special care must be taken to ensure that the voices of the most vulnerable are not inadvertently silenced. Even high-integrity surveys, or qualitative research designs based on long-form interviews and ethnographic observations, are likely to over-represent voices of the relatively secure members of society. Recruiting a large sample initially, and then re-weighting to recover representativeness, is a technical solution. Other kinds of representational concerns—such as the innocuous decision of whether displaced squatters ought to be considered “real” members of Mogadishu at all, or perhaps just dropped from the data?—are murkier. The stakes are potentially quite high. And there may be no easy answers here. It is important to be honest about the complex blend of motivations (humanitarian and security, personal and professional) that bring the researcher into contact with extremely vulnerable communities, since these biases can leak unconsciously into our writing.

Jesse Driscoll is an Associate Professor of Political Science and serves as the chair of the Global Leadership Institute in the School of Global Policy and Strategy at UC-San Diego.