Guest post by Jonathan Powell and Clayton Besaw.

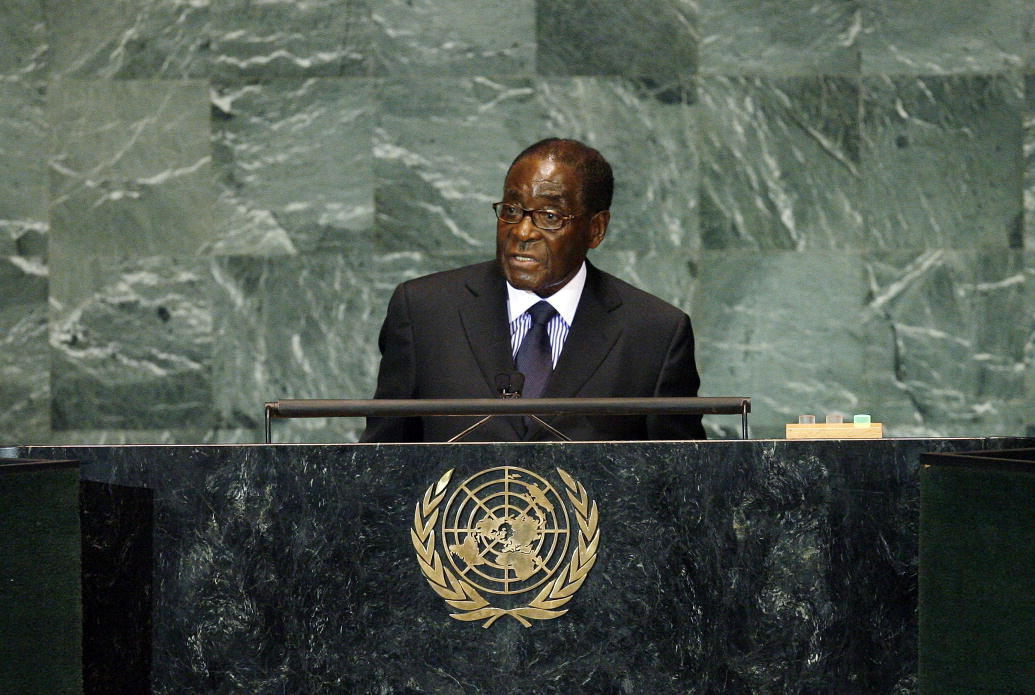

The removal of Robert Mugabe from Zimbabwe’s presidency in November 2017 was the first military coup d’état in a country whose continent has seen security services attempt to seize power hundreds of times. The event brought to power only the second leader the country has known since the end of white minority rule, Emmerson Mnangagwa, himself having been recently purged from Zimbabwe’s Vice Presidency in what many interpreted as an effort to ensure the eventual ascendance of Mugabe’s wife, Grace, to the presidency.

Some—perhaps optimistically—speculated that the coup could put Zimbabwe on a democratic trajectory. The Deputy Director for Southern Africa for Amnesty International—presumably no fan of coups—had noted that “With Mugabe gone, there is a real opportunity for a fresh start for Zimbabwe and a chance to break with history.” Others have pondered whether the ouster of Mugabe could commence an “African Spring” that sees the removal of long-serving dictators such as Cameroon’s Paul Biya and Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni.

Such optimism was overstated. Now-elected president Mnangagwa, aptly nicknamed “the Crocodile,” was perhaps from the start an unlikely source of liberalization. Critically, the very actors that guaranteed Mugabe’s removal—the armed forces—still loom large in Zimbabwean politics. Not surprisingly, the Zimbabwean Armed Forces (ZAF) were criticized for voter intimidation in the lead up to the July 30 poll.

Recent trends in Zimbabwe are not unique. For example, in September 2015 Burkina Faso’s Regiment of Presidential Security attempted to seize power in order to “prevent the disruption of Burkina Faso due to the insecurity of the coming pre-elections.” More directly, the would-be rulers wanted to delay elections and allow the participation of supporters of the recently deposed president Blaise Campaoré, who had been banned from contesting the poll.

Unfortunately, though not surprisingly, research on coups and democratic transitions tend to focus on observed events—so, had Burkina Faso’s 2015 coup succeeded, there would have been no October election, despite it playing a direct role in the coup itself. This is exactly what happened in Mali, when a March 2012 coup led by Amadou Sanogo led to the cancellation of an election scheduled for the following month. Studies intended to assess an electoral cycle-coup link will omit such events, biasing assessments of the relationship.

In an effort to remedy this problem, Curtis Bell and colleagues at One Earth Future (OEF) have created the rulers, elections, and irregular governance dataset (REIGN). REIGN is updated at the beginning of each month and provides systematic data on instances in which any election was called, canceled, delayed, or held. Considering these data reveal just how perilous elections like Zimbabwe’s can be, both before and after the poll.

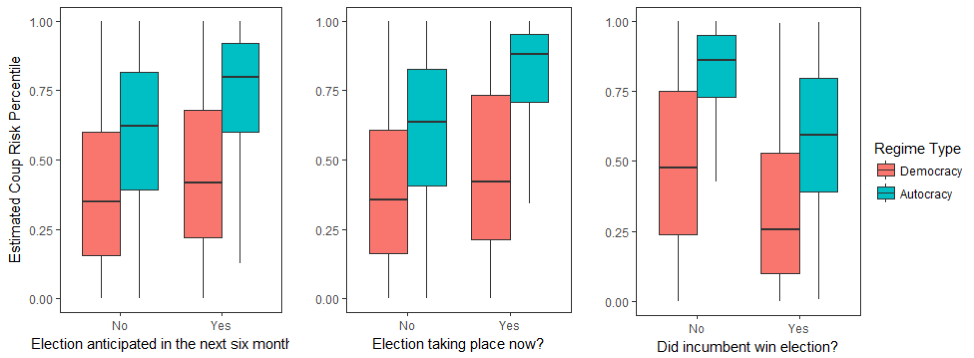

Utilizing OEF’s CoupCast Project, which forecasts monthly coup risk around the world, we look at how countries’ estimated coup risk fluctuates according to electoral cycles, distinguishing between democracies (red) and autocracies (blue). In Figure 1 below, the left plot illustrates how countries’ percentile ranks in coup risk vary depending on whether there is an election anticipated in the next six months, while the center plot looks at months in which an election is scheduled. It is not surprising that authoritarian regimes have a higher overall risk of coups than democracies. However, our assessment shows that the risk of coups increases for both regime categories during election season. Though the jump in risk is more dramatic for authoritarian regimes, the difference represents a statistically significant increase in each category.

Figure 1

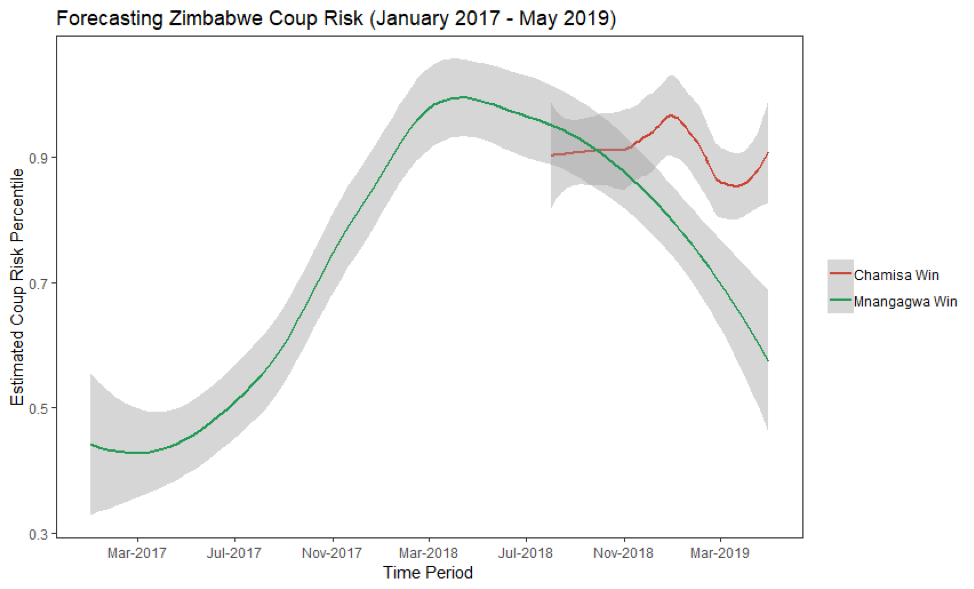

We can also see how prior coup behavior around elections informs Zimbabwe’s coup risk over time. Just after Mugabe’s removal, Zimbabwe’s coup risk was quite high—above the 90th percentile following the coup. This continued to increase as the election grew nearer, ultimately making Zimbabwe the likeliest country in the world to suffer a coup in July.

A prior assassination attempt on Mnangagwa notwithstanding, Zimbabwe appeared to have avoided the fate of many other states in the run up to elections. This should not be taken as a sign of stability, as it is often the election outcome which catalyze coups. Authors such as Tore Wig and Espen Rød have argued that poor incumbent performance in elections can prompt coups in dictatorships, as elites within the regime attempt to prevent losses to the opposition.

This is illustrated in the right plot in Figure 1. Here we look at instances in which an election was held and consider how electoral outcomes influence coup risk. First, similar to prior research, we find that incumbent loss significantly increases coup risk over the following six months. Second, we again find this trend is not limited to dictatorships, as both regime categories witness a significant increase in coup risk when the incumbent loses.

Figure 2

Using an ensemble machine learning methodology, in Figure 2 we forecasted Zimbabwe’s estimated coup risk percentile for Mnangagwa alongside a hypothetical opposition win (Nelson Chamisa). Given inferences from prior elections, while many would have celebrated a ZANU-PF loss, such an outcome would have drastically increased the likelihood of the military re-intervening. This is reflected in our nine-month forecast, as Chamisa’s hypothetical coup risk remains around the 90th percentile with slight volatility while Mnangagwa’s estimated risk steadily declines to nearly pre-coup levels as time progresses.

Moving forward, the case of Zimbabwe and the trends found in our data provide insight into two important issues. First, elections represent a source of potential instability across both democratic and autocratic regimes. Second, scholars should seek to further understand the relationship between political instability and election cycles, including election announcements, delays, and elections that are ultimately canceled.

Jonathan Powell is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Central Florida. Clayton Besaw is a Research Associate at the One Earth Future Foundation.

2 comments