By Cullen Hendrix for Denver Dialogues.

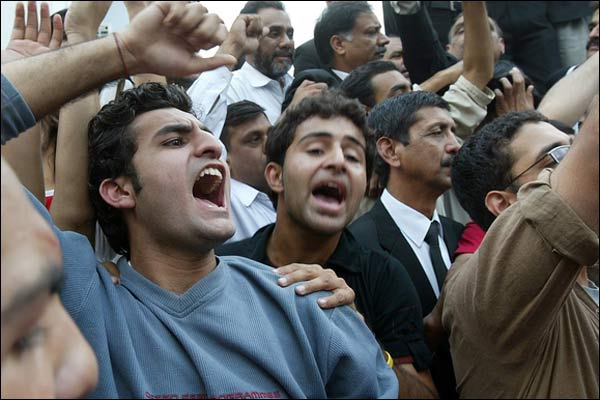

Last week, in response to mass street protests, Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir announced a new cabinet at the same time Sudanese authorities freed a noted opposition leader, Mariam al-Mahdi, who had taken part in mass protests against a state of emergency called on February 22nd. Human Rights Watch has put the death toll associated with these protests—including children and medical staff—at 51. And that figure is now over a month old. Sudan is now on its third cabinet in two years, with previous governments unable to tackle the country’s economic challenges.

So, what’s this got to do with the price of bread?

A lot. No—really. But not everything.

Consumer prices for food—particularly a tripling of the price of government-subsidized bread—were among the grievances that brought Sudanese protesters into the streets. This food price spike has coincided with dwindling and irregular oil supplies, further fueling anti-government animus.

At base, many food-related protests are about expectations of government responsiveness—or lack thereof. Food and fuel prices are the quintessential “kitchen table issue,” important even to those with no interest in politics. Because food is the most basic of all necessities, it is also one that is likely to be viewed as an explicit or implicit political entitlement—populations expect the government to “do something” in times of high prices or scarcity. As incomes increase beyond the subsistence level, access to cheap fuel takes on some of these properties as well.

Part of the bargain rulers in autocratic and hybrid regimes (like Sudan, where some democratic processes commingle with authoritarian institutions) make is simple: in exchange for your acquiescence, I will guarantee you inexpensive access to food and fuel. This is part of what has been called the “Arab Authoritarian Bargain.” Rulers in these regimes manipulate food prices to a significant degree, even to the extent of risking default on their external debt obligations. Indeed, the rising prices in Sudan are associated with currency devaluations and subsidy removals that came at the urging of the International Monetary Fund.

In contrast, citizens of developing democracies—especially those with large rural populations—do not similarly expect their governments to intervene to shield them from high prices. They feel the pinch in the pocketbook: they’re just less likely to expect the government to do something about it.

For this reason, food price-related protests are much more common in democracies than autocracies—but when they occur in autocracies, they are much more destabilizing. In part, this is because much of the benefits of food price subsidies, while often justified as “pro-poor” policies, actually accrue to middle- and upper middle-class households, who have more mobilization potential in times of upheaval. Indeed, one of the major groups behind the current wave of protests is the Sudanese Professionals’ Association (SPA), whose membership consists of doctors, lawyers, and educators: not exactly groups living hand-to-mouth.

This round of protests is not just about food and fuel prices. As Nisrin Elamin and Zachariah Mampilly have persuasively argued, reducing these protests to “bread riots” undersells the longstanding grievances of many Sudanese against a repressive and unresponsive government, and may even feed into the narrative that these protests can be quelled by cabinet reshuffles and better macroeconomic policies. Nevertheless, if we take these long-standing sources of discontent as kindling, the food price spike was a spark.