Guest post by Jonathan Powell and Clayton Besaw.

In a region whose news is often dominated by reports of political instability, it can be easy to overlook milestones that come in the form of events not occurring. In other words, sometimes no news is good news, though such trends may not be readily apparent.

Though a recent March 10 vote in Guinea-Bissau concerned only legislative elections, the poll was not plagued with fears of military intervention, as seen in numerous past elections. Further, armed with the presence of international peacekeepers and countless observers from international actors, President José Mário Vaz is on track to become the first elected president in the nation’s history to complete a full term in office.

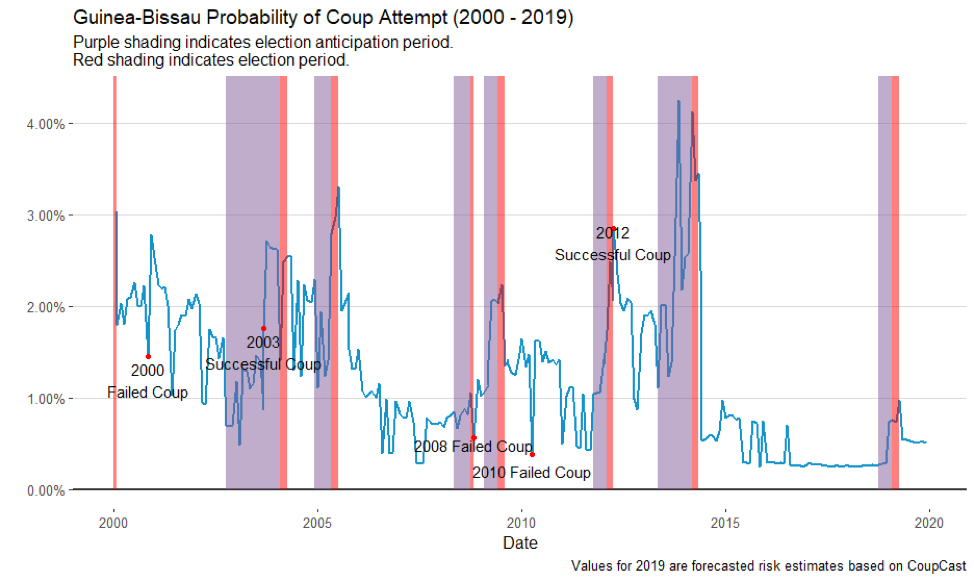

The lead up to elections (pink shading) has traditionally seen Guinea-Bissau ranked among the most likely countries to experience a coup attempt, and 2019 is no exception. That this coincides with an election cycle (purple shading) is not surprising, as the country has seen an intimate connection between elections and coups. However, Guinea-Bissau’s prospects of a coup relapse (blue line) are substantially lower than that seen with past elections.

Guinea-Bissau’s improved prospects for stability are an important departure from the past. Its political history has been marred by numerous interventions by the armed forces. Perhaps foretelling its future history, the country itself was born through a coup. The army’s removal of the Novo Estado regime in Portugal’s 1974 Carnation Revolution both opened the door to Portugal’s transition to democracy and to the independence of its colonies.

Independence was bittersweet, with renowned liberation leader Amilcar Cabral assassinated in 1973. It would ultimately be his brother, Luís, that served as the inaugural leader of an independent Guinea-Bissau. Unfortunately, in a fate shared by a majority of Sub-Saharan Africa’s early political leadership, Luís was removed by a coup in 1980.

The coup leader, João Bernardo “Nino” Vieira, dominated the political scene for nearly two decades. Vieira’s rule was eventually challenged in an abortive 1998 coup attempt led by supporters of the recently ousted head of the armed forces, Ansumane Mané. The attempt served as the opening act in a decade and a half of virtually unprecedented political instability.

Mané’s supporters ushered in a civil war that cost around a thousand lives and displaced over 300,000 people. Following a ceasefire and the reincorporation of rebels into the state, Vieira was ultimately ousted in a May 7 coup the next year

Guinea-Bissau appeared to be on the track toward democratic rule with the subsequent election of Kumba Yala—the poll saw the PAIGC, the dominant party since independence, lose power. However, the democratically elected president was removed in a military coup and the next election returned Vieira to power.

Years later, in 2009, the head of the army, General Tamge na Wai, was killed in a bombing and the quick conclusion was that his rival Vieira was behind it. This belief prompted a faction of soldiers to march on his residence. Within hours, Vieira was brutally assassinated.

His constitutional successor, Raimundo Pereira, oversaw the country until the election of Malam Bacai Sanhá, one of the losing candidates who had accused Vieira of fraud in the prior vote. Pereira eventually returned as interim president a few years later due to Sanhá’s failing health and eventual death. The power vacuum introduced renewed uncertainty to the government.

The lead up to a 2012 presidential run-off saw increased fears of a presumptive Carlos Gomes Júnior administration. Seen as a would-be reformer of the armed forces, Gomes had previously been kidnapped by the armed forces in a failed 2010 coup attempt. Rather than take their chances with a presumptive Gomes victory, the military intervened prior to the vote in a 2012 coup, removing the Pereira government and cancelling the election.

Resetting the electoral process yet again, the 2014 presidential election saw José Mário Vaz defeat the military’s preferred candidate, Nuno Gomes Nabiam. Vaz had himself been removed as Prime Minister in the 2012 coup. The result led to speculation of further intervention, particularly after Nabiam challenged the results.

Further complicating the matter, Vaz wasted no time in exacerbating rivalries in the government and within his own party. This was especially the case with Prime Minister Pereira. Vaz dismissed him in August 2015 and attempted to circumvent the parliament by directly appointing a successor, Baciro Djá. The appointment was ultimately ruled unconstitutional by the courts, and the position of Prime Minister continued as a revolving door.

Carlos Correia briefly held the post in 2015. A second Djá tenure fared no better, as he was expelled from the party that November. Umaro Sissoco Embaló fared slightly better, lasting 14 months before resigning. His successor, Artur Silva, was out within three months. Aristides Gomes followed him into the position.

As the recent history of Guinea-Bissau indicates, power struggles and deep political rivalries raise the stakes of electoral outcomes, making elections all the more precarious. This type of political political deadlock is precisely the type of scenario in which militaries often intervene and are celebrated for doing so.

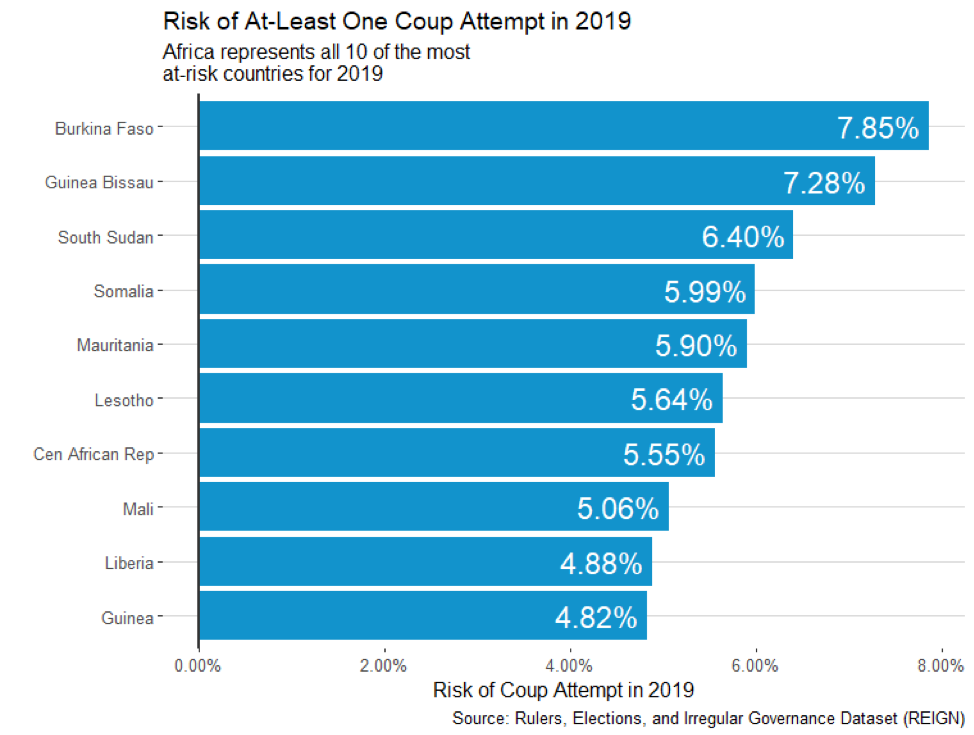

Not surprisingly, these trends make Guinea-Bissau one of the most likely places to experience a coup in 2019.

Using CoupCast, a machine learning based forecasting system, we estimate the risk of at least one coup attempt taking place in every country around the globe. Guinea-Bissau’s estimated risk of at least one coup attempt in 2019 is 7.28% and is currently the second highest of all countries.

Guinea-Bissau’s risk is largely driven by the recent history of coup events and the slate of elections this year. However, CoupCast shows that Guinea-Bissau’s relatively high risk for 2019 is quite low within its historical context. Risk for 2019 will peak around the election season and should substantially decrease if the anticipated presidential election happens without incident.

The recent legislative election was declared to be a successful milestone for democracy in the country. This bodes well for the prospects of a peaceful presidential election and for the democratic process going forward. Given these facts, one can look at Guinea-Bissau with cautious optimism. While relative coup risk is still high, the continuance of peaceful electoral politics may indicate that the shadow of coup-related regime change remains in the past.

Jonathan Powell is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Central Florida. Clayton Besaw is a Research Associate at the One Earth Future Foundation.