Guest post by Anup Phayal.

In recent years, protection of civilians has become a key mandate for UN peacekeeping missions. A number of studies show that deploying peacekeepers in a post-conflict country can sustain the peace and lower violence against civilians. For this reason, there is a growing consensus to increase the military capacity of peacekeepers, not only to deter potential perpetrators, but also to conduct counter-insurgency style operations against spoilers of peace (see here, here and here). Yet, the core principles of peacekeeping—such as neutrality, minimal use of force, and dialogue—are incompatible with the preference for a military-centric approach, even though interventions today warrant some degree of coercive capacity against armed violence by opportunist actors. Furthermore, participating troops in “peacekeeping” missions often have less incentive to take risk by fighting against local actors. In light of this complexity, it is difficult to assess how military peacekeepers can best achieve the goal of civilian protection.

In a recently published paper in International Interactions, I look at two key questions related to the peacekeeping puzzle mentioned above. First, are UN peacekeeping troops effective at saving civilian lives at the local level? I evaluate this question using a focused study and a unique methodological approach that minimizes the selection bias problems inherent in many studies of UN peacekeeping. Second, I explore the causal mechanism underlying the effectiveness of peacekeeping—if missions are successful, is it due to their military capacity to coerce or some other non-coercive attribute or activity?

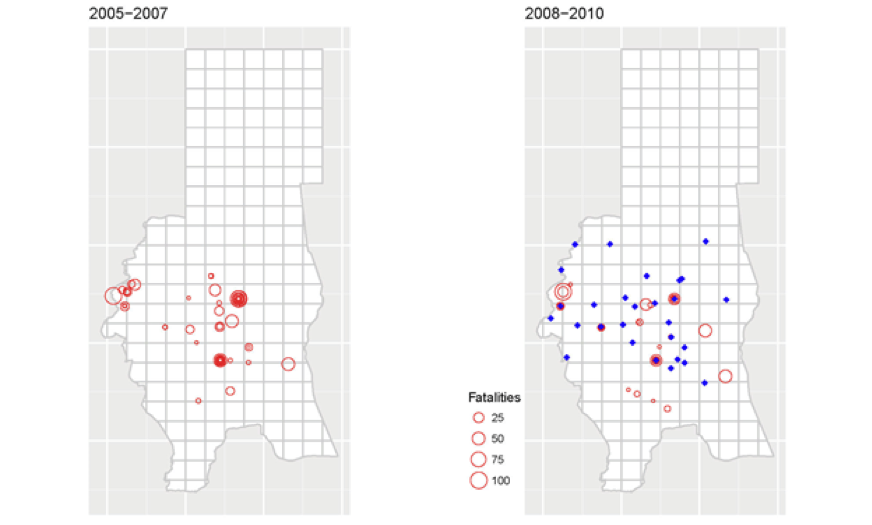

To examine these questions, I conduct a micro-level study of one of the largest peacekeeping missions in recent history, the UN-African Union Mission in Darfur, launched in 2008. I start by dividing the region of Darfur into 214 small grid-cells and track civilian killings in each grid-cell before and after the deployment of peacekeepers. Using a difference-in-differences technique, I then compare the level of civilian killings across grid-cells and estimate the effect of peacekeeping deployment. This methodological strategy also allows me to isolate the impact of the military coercive capacity of deployed peacekeepers.

The study finds that the presence of peacekeepers reduces the extent of civilian killings at the local level. This finding is in-line with other cross-country studies that have found similar results (see here and here), and it is reassuring that deploying peacekeepers has a positive impact at the local level, even in a highly violent context like Darfur. However, contrary to the explanation provided by past studies, my results indicate that enhancing the coercive capacity of peacekeepers does not lead to greater reduction in one-sided violence against civilians.

One-sided civilian killings before and after the deployment of UNAMID

While the presence and number of peacekeeping units in a grid-cell are found to lower the level of violence against civilians, there was no evidence to suggest that militarily more professional units are better at curtailing such violence. In other words, compared to no presence, having peacekeeping units from any country saves more civilian lives. Interestingly, peacekeeping units from countries that spend more on their militaries do not necessarily do a better job of protecting civilians. These findings raise two questions that challenge the militarization trend in peacekeeping.

First, as I argue in the paper, rather than coercive military force, it seems that other aspects of peacekeeper deployments—such as monitoring, verification, and reporting—may have contributed more to saving civilian lives. Monitoring and reporting raise the cost for potential perpetrators. Since such violent perpetrators are often key political actors or groups, reports from the field and, subsequently, from UN headquarters can raise political costs and restrain behavior. This restraining effect has clear and direct implications for scholar and policymakers—for instance, it suggests that policymakers should place more emphasis on non-coercive aspects of peacekeeping during planning, resource allocation, and pre-deployment training for a peacekeeping mission. Understanding the precise impacts of military and non-military attributes of peacekeepers is understudied and these findings highlight the need to examine such dynamics further.

Second, the “non-finding” that enhancing military capacity does not lead to a significant boost in civilian protection highlights a key problem associated with militaries in peacekeeping. Their decision to use the force in protecting civilian lives directly correlates with their willingness to take risk, which in turn is guided by the generally risk-averse policies of respective troop contributing countries (TCC). While this study finds that a mere presence and reporting could provide some level of civilian protection, it leaves future research to find how their willingness to take risks or their interest in the mission might enhance the outcome of civilian protection. If so, rather than enhancing physical military capacity, focus should first be on institutional and policy reforms that cultivate greater commitment from the TCCs.

Anup Phayal is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Public and International Affairs at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

1 comment

This is an interesting finding. Too often public debates about security rely on the assumption that coercion is central to changing behavior in desired directions. That there is no difference between units with more or less coercive capacity is significant to our understanding of force in conflict more broadly. For instance, counterterrorism policies based on coercion traditionally prove less efficacious in reducing violence.