Guest post by Khaled Terkawi.

When I was in the old Homs city in 2012, the rebels arrested several elements of Assad’s ‘civil defense’ force, also called ‘Popular Committees.’ It struck me at the time that those people were Syrian nationals who all received training in camps near Tehran, the Iranian capital. At the same time, Iranian officers were providing support to Assad’s National Defense Forces through field training and supervision of military actions.

Although Iran’s military engagement in Syria was initially focused on providing training, logistical, and technical support to Assad’s regime, the relationship quickly moved towards deeper integration of military systems and creation of separate military structures directly linked to Iran.

This was exemplified, for instance, by the foreigners who came to Syria from Lebanon, Afghanistan, and other countries. In 2017, when we were displaced from the al-Wa’r neighborhood in Homs, our convoy—accompanied by Russian forces—cut through areas of Eastern North Homs (an area under the Iranian influence). The raised banners and faces of the soldiers we saw in that area showed that they were foreigners.

One could also see Iranian influence as some Syrian Sunnis and Alawites serving in Assad’s forces began to point towards teachings of Shiite religious doctrine as moral and religious justification for the fierce war they were waging against their fellow Syrians. In addition to the military training they received from the Iranian officers, there was compulsory education on elements of faith and religion by clerics from Iran.

To solidify their foothold, Iran began to recruit Sunni militias and subsequently expose them to tenets of Iranian Shiite ideology. More than just providing bodies for the fighting effort, these Sunni groups provided a deeper foundation for an alliance with Iran within the Sunni community, adding to Iran’s early successes in winning over groups of Alawite militias from different parts of Syria.

Despite these early successes, Iran seems to be aware that it cannot rely solely on such militias as a future anchor in Syria, especially given the broader geopolitical processes playing out in the country. As a result, Iran has also made efforts to deepen its social and economic engagement in Syria.

Examples of this effort include the open loans Iran provided to the Assad regime to finance the activities of the “government and its institutions.” Iran has invested heavily in Syrian infrastructure—the country is currently under contract to invest in Syria’s energy sector through the construction of a power station in Latakia on the Syrian coast, situated just few miles from Europe (the contracts are worth 400 million euros, with projected production of 540 MW of electricity), and is responsible for the reconstruction of electricity stations in Homs, Deir El-Zur and Aleppo. Iranian backers have also pledged investments in the phosphate fields in eastern Homs—as well as a new refinery in the same area—and oil fields near Deir El-Zur.

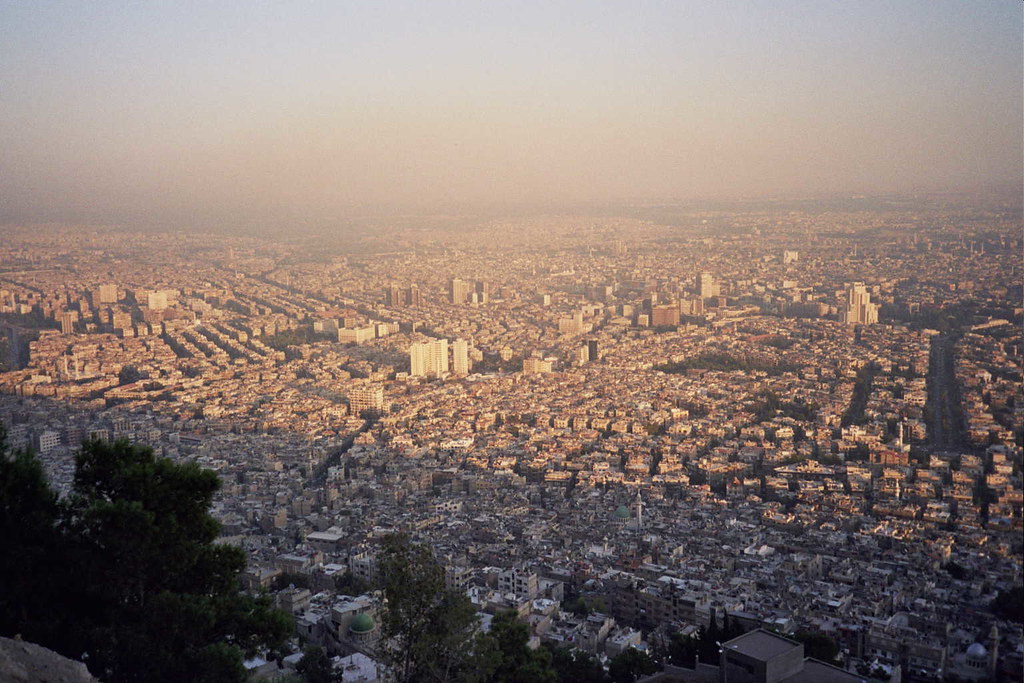

In addition, Iraqi and Iranian merchants are seeking to buy more real estate properties inside Damascus as well as investing in the Mezzeh gardens and some other projects around the capital. This is where Hezbollah, one of the key torch-bearers of Iranian ideology, controls large areas on the Syrian-Lebanese border and inside the Syrian territory in both Damascus and Homs.

At the end of last year, the Syrian Ministry of Housing finalized a contract with Iranian businesspeople to build 30,000 housing units in Damascus, Homs, and Aleppo, while negotiations are under way to build additional units at Deir El-Zur and rural areas of Damascus.

Iran has also worked to secure a foothold in the region via direct engagement with Syrian communities through their religious and political infrastructure. Iranian officials and senior military officers regularly visit influential local Syrian officials to garner their support for Iranian interests using various tactics, including supporting bids for promotion to higher government offices or protecting them from dismissal. Illustratively, a contract was signed to invest in 5,000 hectares of agricultural areas in the eastern regions at the community level. However, a significant string was attached: the investment was to be accompanied by a broad campaign by Iranian clerics to attract the local Sunni population and change their religious ideology. This ‘social engineering project’ used a wide array of tools, including food and money handouts, in addition to intensive ‘courses’ by Shiite clerics.

The international community appears disinterested in this process. Its engagement with Iran is focused on Iran’s nuclear capacity, which is largely separate from the situation in Syria. Further, the forcible displacement of the local Sunni population, in which Iran played a pivotal role, has been a critical part of establishing a permanent pro-Iranian social structure in Syria. While Iran is effectively taking over the country, the Syrian opposition is preoccupied with the illusion of reaching a political solution under the current circumstances. In reality, the opposition is hedging all its bets on draft constitutional amendments and the possibility of elections in Syria, while the majority capable of influencing the outcome of such elections is being effectively removed from the equation.

If the “Iranisation” of Syria continues at the same pace and with the same tactics, the consequences of such a tectonic demographic change of Syrian society would reverberate far beyond our borders.

Khaled Terkawi is a researcher and writer from Homs. He is a Homs coordinator for the Syrian Association for Citizens’ Dignity.