Guest post by Christoph Valentin Steinert.

Armed conflicts are inextricably linked with substantial injustices. While no policy can revert such harms, several instruments of transitional justice have been developed to alleviate their consequences. These instruments include—most notably—post-conflict trials that are frequently deemed indispensable to restore the dignity of victims. Particularly since the end of the Cold War, there has been an unprecedented surge of prosecutions after armed conflicts, a phenomenon described as the justice cascade. Pushed by the human rights community, the creation of accountability for perpetrators of human rights violations is nowadays regarded as a key objective of post-conflict reconstruction. However, do post-conflict trials deliver what they promise?

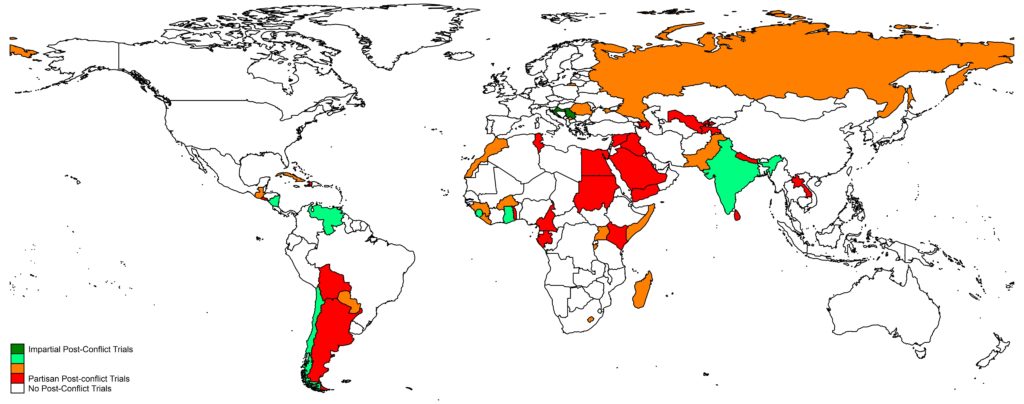

To answer this question, I collected expert ratings on all major post-conflict trials implemented between 1946 and 2006 as recorded by the Post-Conflict Justice Dataset. Country experts—identified by publications on the respective post-conflict contexts—rated several items measuring the fairness of these post-conflict trials. The results demonstrate that the majority of the post-conflict trials (72%) were partisan, with substantial biases against the political opposition. Biased post-conflict trials were spread around the globe while only one post-conflict trial, namely the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, was deemed as largely unbiased (see Figure 1). Beyond the numerical ratings, several experts provided detailed descriptions about the post-conflict trials under investigation. They stated, for instance, that “there was no attempt at reconciliation” (Prof. Christina Cliff on Burundi 1965), that “supporters of the regime were generally not indicted” (Prof. Jean-Phillipe Belleau on Haiti 1991), that “the process focused only on a very narrow group of perpetrators” (Prof. Randall Fegley on Equatorial Guinea 1979), that “confessions [were] enforced by torture” (Prof. Patrick Peebles on Sri Lanka 1971), or that there was a “one-sided show trial” (Prof. Sheila Carapico on North Yemen 1986).

In light of these findings, it becomes clear that post-conflict trials are not necessarily an instrument to create accountability for perpetrators of violence. Instead, they are frequently manipulated by post-conflict governments that seek to consolidate their position in power. Such political biases tend to result in excessive punishments of opposition forces while government allies are systematically pardoned. Hence, there is no inherent value in post-conflict prosecutions when judicial independence is under threat. How can we identify post-conflict contexts where political manipulations are most likely to occur? And which types of post-conflict trials are most likely to be biased?

Figure 1: Post-conflict trials (1946-2006)

By systematically studying predictors of biased post-conflict trials, I find that all partisan trials in the studied time period have been domestically implemented. None of them has been implemented by external actors in an international tribunal. In contrast, 80% of the internationally implemented post-conflict criminal prosecutions have been classified as impartial. Some scholars have criticized such international criminal prosecutions for their lack of legitimacy among domestic populations; however, given that domestic prosecutions are particularly prone to biases, it could be replied that international tribunals are essential to provide impartial proceedings.

These findings are particularly prescient in the wake of decisive, one-sided battlefield outcomes—81% of the partisan post-conflict trials were implemented after victories, while less than 10% were implemented after bargained solutions. In a multivariate model including all global post-conflict environments between 1946 and 2006, victorious battle-outcomes are a significant predictor for the implementation of partisan post-conflict trials. Hence, criminal justice after victories on the battlefield tends to take the shape of one-sided victor’s justice.

Beyond that, the majority of partisan post-conflict trials were implemented after internal conflicts and they were more likely after territorial conflicts. Partisan post-conflict trials were also more frequently combined with amnesties than impartial proceedings. Impartial post-conflict trials, in contrast, were significantly more likely in rich countries with high levels of GDP per capita. This suggests that certain economic capacities are essential to ensure unbiased proceedings. Further, the likelihood of impartial post-conflict trials is higher after conflicts with greater numbers of battle deaths. This could imply that accountability-seeking is more likely if conflicts were particularly destructive.

What can be learned from these findings? While important ethical and legal rationales call for extensive prosecutions after armed conflicts, it is a precondition to consider whether judicial independence is under threat. If prosecutions are likely to be politically biased, they neither deliver accountability nor do they contribute to reconciliation. Just as elections do not necessarily guarantee democracy, post-conflict trials are no guarantee of justice. Therefore, this study suggests that the transitional justice community should pay close attention to potential indicators for biased proceedings, such as victories of one conflict party or a lack of economic resources. In such contexts, international tribunals implemented by impartial actors may be the preferred option to ensure perpetrators of human rights violations are held accountable.

Christoph Valentin Steinert is a PhD student in the Graduate School for Economic and Social Science at the University of Mannheim.