By Page Fortna

Sri Lankans went to the polls on Friday, 10+ years after a long-running civil war, and almost 7 months after the Easter terrorist attacks. With 52 percent of the vote, the overwhelming victor was Gotabaya Rajapaksa, or Gota, as he is generally known. Gota is the brother of former President Mahinda Rajapaksa, and served as his Defense Minister during the final phase of the war.

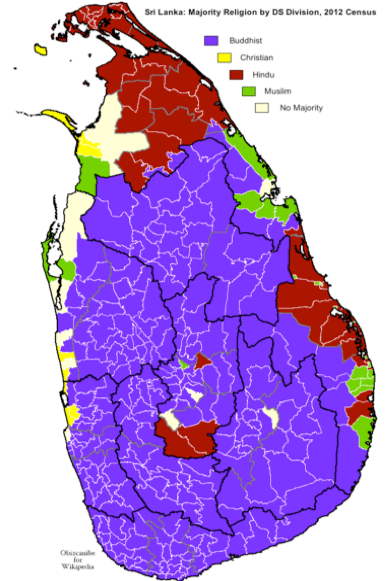

The brothers Rajapaksa are controversial figures: reviled among the Tamil minority for brutal conduct to wipe out the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE, or Tamil Tigers) who fought to secede, and revered for exactly the same thing among nationalist Sinhalese Buddhists. (Yes, while it may sound odd to Americans accustomed to associating Buddhism with pacifism, a virulent strain of fundamentalist, nationalist Buddhism is alive and well in many Buddhist majority countries, including Sri Lanka and Myanmar. Some nationalist Buddhists hesitate to swat a mosquito or step on an ant, but are capable of horrendous violence against Tamil or Muslim minorities.)

Sri Lanka suffered two political crises in the last year (when I happened to be there for fieldwork studying the civil war): a constitutional crisis, and a massive terrorist attack. In October, the uneasy alliance between then-President Sirisena and Prime Minister Wickremesinghe, who had united to defeat Mahinda Rajapaksa in the 2015 elections, fell apart. The President attempted to fire the PM and install Mahinda in his place. A constitutional crisis and almost two months of political drama ensued: Wickremesinghe refused to leave the PM’s official residence, protesters and counter-protesters took to the streets, Parliament was prorogued, the prorogation was over-ruled, fisticuffs broke out in Parliament, and questions arose about whether the Tamil, Sinhala, and English versions of the Constitution all said the same thing. Much to many people’s surprise, civil society turned out in strength to oppose the move; Members of Parliament were not as easily bought off or intimidated as some thought; and the Supreme Court showed more independence than many expected, ultimately rejecting the firing and ruling for Wickremesinghe. Despite the drama, the episode’s conclusion seemed to bode well for a strengthening of democracy and the rule of law.

But the President and the prime minister, who hadn’t worked well together beforehand, were now barely on speaking terms. So when intelligence came from India of an imminent attack on churches and hotels on Easter Sunday by a tiny, fringe fundamentalist Islamist group, no one did anything. Whether this was entirely the result of a deeply divided and therefore dysfunctional government, or something more sinister, as more conspiracy minded folks suspected, will probably never be known. The terrorist attacks killed approximately 250 people in (predominantly Tamil) Christian churches and at high-end hotels frequented by Western tourists. The perpetrators were rounded up that afternoon (attesting to how much intelligence services knew about them and their whereabouts ahead of time). The country shut down completely for two weeks, and reprisal attacks on Muslim communities festered for even longer.

Meanwhile, the military rolled out of its barracks and set up checkpoints throughout Tamil areas (even though the attack was perpetrated against rather than by Tamils). There was markedly little security presence in Muslim communities affected by the reprisal attacks. As a Tamil service industry employee said to me in Jaffna, when I commented on the security presence: “it’s their hobby.”

The trajectory Sri Lanka seemed to be on after the constitutional crisis was overturned in a morning by the bombings. The attack by a fringe Muslim group affiliated with ISIS played right into nationalist Sinhalese rhetoric, no matter that the Muslim community in Kattankudy, from which the attackers came, had themselves pleaded with the authorities to deal with the group’s leader as a dangerous extremist in their midst. The overwhelming desire for security and a collective almost PTSD-like reaction to an attack that brought back horrific memories of the terrorism of the civil war meant that most of the Sinhalese majority would set aside any concerns about the Rajapaksas. Anti-Western and anti-Christian attacks by a group connected to ISIS similarly quieted international calls for accountability and human rights. The brutal conduct of the final stages of the war and the authoritarian tendencies of the previous government went from potential liabilities to electoral assets overnight. Gota Rajapaksa quickly emerged as the front-runner.

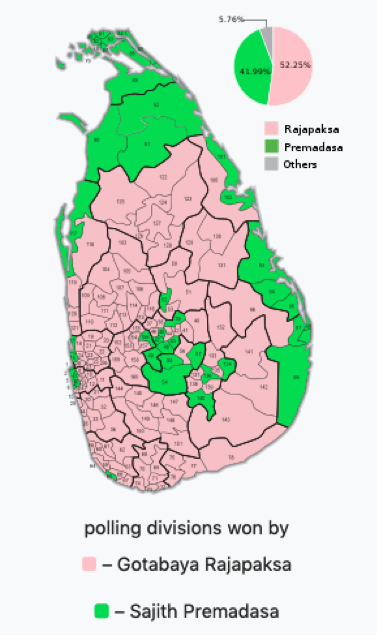

The electoral map reflects the deep divisions that remain in Sri Lanka. Around the North and Eastern edges of the island, the population is overwhelming Tamil-speaking minorities (including Hindu and Christian Tamils and Muslims who also speak Tamil but often identify as a separate ethnic group). The hill country in central Sri Lanka is populated by Tamil tea workers brought in as indentured laborers by the British. All of these areas voted overwhelmingly for Rajapaksa’s main opponent Sajith Premadasa (scion of an established political family, his father Ranasinghe Premadasa was President when he was assassinated by the Tamil Tigers in 1993). Despite or perhaps because of his family history, Premadasa was considered more likely to pick up his party’s mantle of constitutional reform and reconciliation among Sri Lanka’s ethnic groups.

Immediate prospects for such reconciliation, accountability for war crimes, and constitutional reform are now on ice. Whether Gota Rajapaksa governs, as many expect, in a way that exacerbates the old and new wounds between Tamils, Muslims, and the Sinhala majority, or whether he ameliorates these tensions (in a Nixon-goes-to China manner) remains to be seen.