Guest post by Sara Plana and Sanne Verschuren

The analogy of the COVID-19 crisis as war is inescapable. At first, the comparison seems apt: the disease’s global reach, the death toll, the active “threat” of the virus, and the public sacrifice required to fight it seem more similar to a global war than to a geographically confined natural disaster, constitutional crisis, or another form of sudden, transnational change.

But the way the analogy is used betrays an idealized vision of war. Although war is sometimes imagined to unite society against a common enemy and justify common sacrifice for the public good, in war—as in the COVID-19 crisis—not everyone on the frontline chose to be there, not all efforts to rally people around a common threat work, and not all parts of society are sacrificing and suffering equally. The main lessons of war for the COVID-19 crisis may, therefore, be the ways it could divide, as much as unite, society.

Frontline “Heroes”

Healthcare practitioners often invoke the war metaphor to convey the horrors they are experiencing during the COVID-19 crisis. Doctors make life-or-death decisions with heightened emotions and stakes—similar to military commanders during wartime. In the rush to continue their mission, doctors and nurses describe having little time to process death, only to sit with that reality later on—not a strange feeling for service members. Their personal lives have taken on some qualities of deployments, including working long hours in dangerous circumstances with little protective gear and in prolonged isolation from their families.

By amplifying the human stories of healthcare workers battling the virus, the hope is that the public will do more than just thank them for their service. Leaders, activists, and healthcare workers have utilized the comparison to advocate for steps to “protect the people who are protecting us,” by increasing supplies of protective equipment or pushing for hazard pay, akin to deployment bonuses.

But the frame of healthcare workers as “heroes” voluntarily going into the line of fire masks that not everyone risking their lives signed up to be there.

In war, the degree to which all-volunteer forces are voluntary or wartime drafts are actually universal or equitable is fiercely debated. Like in so many wars, some on the frontlines of COVID-19 volunteered to serve, but others were called to service involuntarily.

In many hospitals, medical personnel have been redirected from their primary specializations to assist with COVID-19 cases. As one doctor in New York put it, “I don’t want to be a hero…I would way rather not be doing this.”

This is all especially true for essential workers such as grocery store clerks, sanitation workers, and truck drivers. They did not consent to be constantly exposed to an infectious disease as part of their jobs. They are being involuntarily “drafted” into combatting the virus in their own way, but political commentators have been slow to include them as “heroes” of COVID-19.

The world will soon be forced to grapple with the responsibility society has to the “heroes” who have been asked to risk their lives in the wake of COVID-19, especially if they were given no other choice.

COVID-19 Crisis Leadership as Wartime Leadership

From Chinese state media framing Xi Jinping as the “commander of the decisive battle” to President Trump’s self-labeling as a wartime president, leaders across the globe have likened their role to that of wartime leaders. Like the wartime presidents they allude to, they must make tough choices about the best way to combat the disease, or about the possible effects of policy measures with imperfect information about the threat.

Thinking of crisis management as management during war misses a few key differences, however. For one, in the COVID-19 crisis, leaders must mobilize society not just to support the main effort, but to be the main effort. Countering coronavirus—a global, diffuse and invisible threat—requires the cooperation of a range of stakeholders, including health experts, economists, scientists, and local politicians. The image of war also tends to pit states against one another, but in public-health crises, sharing information and expertise across borders is necessary for countering the virus quickly. In this crisis, the imperative to rally multiple stakeholders—at home and abroad—may be even higher than during war.

By using the war analogy to appeal to a sense of urgency and an existential, common threat, political leaders try to rally citizens to take steps—from marshaling industrial resources to abiding by measures of social distancing—to “win the war.” This overlooks that past efforts to rapidly mobilize during wars, even in the most existential ones, have been heavily contested. Being a “wartime president” alone is no panacea for getting everyone on board with your plans, which clearly surfaced in recent days.

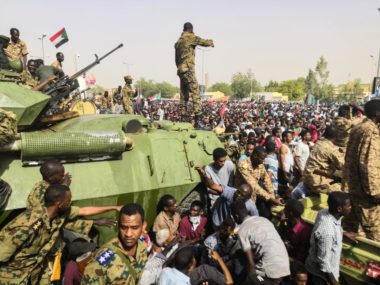

The use of the war metaphor masks a darker reality of how some leaders behave during times of war. Like in war, some leaders took advantage of this crisis to adopt dangerous policies, including quelling dissent, adopting mass surveillance, marginalizing vulnerable groups, and circumventing the rules of transparency and democratic governance.

The Wartime Society

Leaders and commentators have also used the war metaphor to instill collective solidarity and self-sacrifice. However, this rhetoric masks how the burden of COVID-19 is unequally distributed among the population, often amplifying society’s pre-existing inequalities.

In the past, populations have used the legacy of war to propel societies out of pre-war inequalities, compensating for societal sacrifice. Those who served have themselves employed the rhetoric of service and sacrifice to advocate for more rights or social programs in the post-war context. Benefits extended to American Civil War veterans sowed the seeds of the modern social security system, and African Americans leaned on the contradiction between their service during World War II and the inequalities they experienced back home to advocate for expanded civil rights in the 1940s and 50s.

Today, healthcare and essential workers have started invoking their sacrifice in appeals to businesses and governments to expand rights and protections. It remains an open question, however, whether the call-sign of service and sacrifice will help essential workers and other social groups to muster the necessary support for lasting social, institutional change, like many have done before them.

Placing the COVID-19 crisis in the category of war has certain advantages: Justifying sacrifice, taking extreme and unprecedented effort to combat the threat, and mobilizing the population to ultimately achieve victory. In some ways, however, the use of war language might conceal more than it illuminates, including the disproportionate call to arms on a distinct group rather than the whole population, the dark sides of wartime leadership, and the uneven fall-out of war.

Sara Plana is a PhD candidate at MIT Political Science and Security Studies Program. Her research interests include proxy warfare, civil-military relations, military organizational behavior, and use of force. Sanne Verschuren is a Ph.D. Candidate at Brown University. Her research interests include the development of military technology and shifts in military strategy and tactics, and the role of ideas and norms therein, as well as the global arms trade and the politics of deterrence.