By guest contributors Maria J. Stephan and Candace Rondeaux, and PV@G editor Erica Chenoweth.

Nationwide protests against police brutality following George Floyd’s murder are the broadest and most persistent in US history. They have laid bare the racism that pervades American society—and demonstrated the willingness of Americans to take to the streets and resist oppression, even in the midst of a pandemic. Americans must continue demanding an end to white supremacy and follow the lead of Black organizers to galvanize a similar flexing of civic muscle to help ensure democratic continuity come November. With elections four months away, and the rule of law under steady attack, people power could prove decisive in ensuring a constitutional transfer of power without violence.

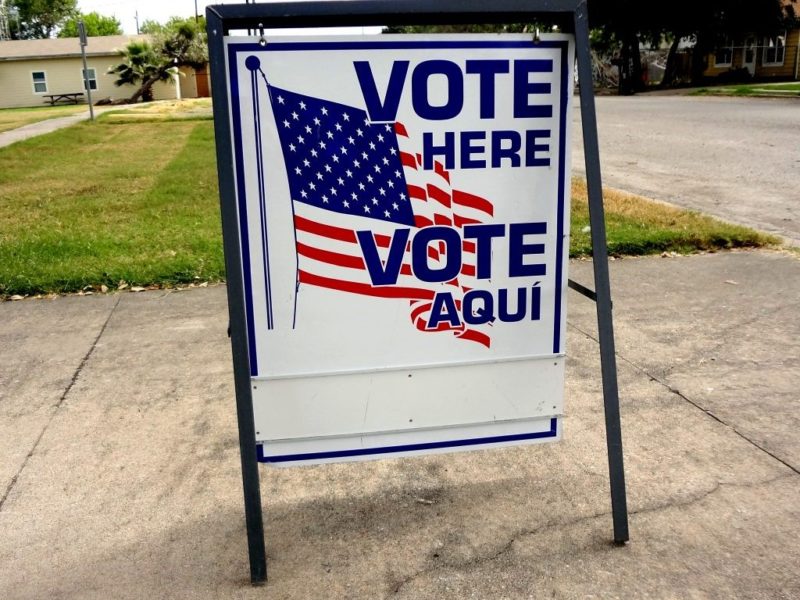

Analysts have developed a number of doomsday scenarios for November. The election could be postponed or canceled. A state of emergency could be declared and polling stations shut down. Hostile foreign powers could ramp up their interference in the election—through the targeted spread of misinformation, cyberattacks on voting machines or databases, or political harassment of candidates—in ways that affect the outcome. Even if the elections go forward fairly smoothly, the results will likely take longer to process because of the anticipated higher volume of mail-in and absentee ballots. Disputes over mail-in ballots are only one of several triggers that could cause the outcome to be challenged or rejected altogether.

Well-armed paramilitaries could come out to the streets no matter which candidate is declared the victor. Lone wolf actors could set off a chain reaction of escalating violence. Indeed, experts on mass atrocities have cited risk factors—including widening social and economic inequality, persistent violence against racial minorities, a surge of inflammatory political rhetoric, the rise of paramilitary groups, and the polarization of political parties along mainly racial or religious lines—as being particularly worrisome in the leadup to the election.

While it is difficult to quantify the risks associated with various elections-related scenarios, the stakes could not be higher. In the event that there is evidence of widespread voter suppression in the lead-up to the election or on November 3, disgruntled or disenfranchised citizens who take to the streets in mass protests could be met with police or paramilitary violence, or both, resulting in mass casualties. Already, far-right militant groups and vigilantes have increased their public visibility and shown a willingness to go to battle with ideological opponents. If mass violence erupts—a distinct possibility in a country awash in guns and where a surprisingly high number of Republicans and Democrats have said that violence may be justified if the other party wins the election—the outcome could be civil war. If the results of the election are disputed or ignored, or the military is called on to suppress constitutionally protected protests and public gatherings, if martial law or emergency decrees are declared, and the constitutional transfer of power is not respected, mass violence or civil war could similarly result.

Lawyers are preparing for these contingencies. But in countries where institutional checks and balances and democratic norms are rapidly eroding, legal challenges and other institutional channels are usually insufficient to meet worse case scenarios. Extra-institutional pressure—through mass nonviolent civil resistance—may be required to protect and defend the vote while warding off the specter of mass violence. It would be foolhardy to assume that this country is immune from democratic backsliding. Scholars of authoritarianism have been warning of an erosion of democratic norms and practices in the US. The bipartisan Freedom House organization has charted a steady decline in the US “global freedom” score—its most recent ranking places 51 countries ahead of the United States.

Therefore, in addition to learning from our own civil rights history, Americans could also learn from experiences in semi-authoritarian contexts like Serbia (2000), Ukraine (2005), and the Gambia (2017), where sustained protests and other forms of non-cooperation, including boycotts and general strikes involving large segments of the population, challenged leaders who illegally kept themselves in power. In Serbia, in addition to building pressure through mass demonstrations, activists prepared for the election by setting up local election monitoring and verification networks, reporting local-level vote counts to an independent office in Belgrade. This allowed pro-democracy advocates to contest the false election results announced by the incumbent Slobodan Milosevic, preventing him from stealing the election. A modified application of parallel vote tabulation, now a standard tool of democracy promotion, could be useful for the US elections.

Scholars have documented other cases where populations have used mass civil resistance to prevent coups d’etat and to defend against illegal usurpations of executive power. In each of these cases, the protestors referred to their own constitutions, and the need to protect the constitutional order, to justify their turn to mass civil resistance and civil disobedience. In most cases, organizers and activists worked in advance to build relationships with various influential constituencies—such as members of opposition and majority political parties, civil servants, mayors and city council members, business leaders, religious authorities, and even police and military officials—to build broad-based, cross-cutting support for the use of civil resistance to protect the vote.

Of course, the use of mass civil resistance to challenge or reverse the outcome of a free and fair November election would be both unjustified and deeply problematic. But it is better to prepare for any contingency than to be caught off guard by a worst-case scenario. What is needed to prepare the country to defend the vote and avoid violence in the event that the elections go sideways?

First, Americans need to support a “movement of movements” that brings together key groups that have been organizing to protect and expand voting rights, resist racism and police brutality, protect undocumented immigrants, fight sexual harassment and violence, defend the environment, address economic inequality, and demand government accountability. These groups are demanding that the country lives up to its core ideals of liberty and justice for all. Movements like Black Lives Matter and the Movement for Black Lives, the Poor People’s Campaign, the DREAMers, the Sunrise movement, Indivisible, and the Women’s March have spent years organizing at the community and national levels. And the recent nationwide George Floyd protests have uncovered a vast new array of movement pressure points.

Bringing these movements together under a single banner of mobilizing voters, training people in nonviolent direct action, countering fraud and disinformation, and preparing to defend the vote—including through civil resistance and community-led violence prevention measures—could help ensure the election is free and fair. These movements, which include or are allied with unions, lawyers, foundations, and inter-faith groups, could join forces with the think tanks, academic institutions, and professional associations that have begun planning various election-related scenarios.

Second, these groups could jointly analyze potential key pillars of support for anti-democratic actions and plan out how to keep them on the democratic path. All governments ultimately depend on the consent and cooperation of ordinary people to stay in power. They need civil servants to run the bureaucracy, workers and professionals to keep the infrastructure intact, religious institutions to provide them with moral legitimacy, businesses to keep the economy afloat, and security forces to obey orders.

Loyalties within these pillars are fluid and can shift. We have already seen high-ranking military officers signal their adherence to the rule of law and their unwillingness to obey executive orders to use troops to quell protestor dissent. The threat of a general strike by the Association of Flight Attendants helped end the government shutdown in 2018-19. Local city councils have adopted policies to resist the deportation of undocumented immigrants. Identifying these leverage points and designing actions to pressure and persuade members of these pillars to join the pro-democracy fight is key to building mass participation, a key ingredient of successful nonviolent campaigns. Studying cases and techniques that populations around the world have used to nonviolently defend against coups and other attempts to illegally subvert the democratic order would also help prepare for worst case scenarios.

Third, messaging and information sharing will also be critical components for any movement. If 2016 taught us anything, it is that there is a strong feedback loop between foreign disinformation, locally driven misinformation, and the amplification of political grievances. Movement leaders and activists may have to work twice as hard this time around to figure out where there are gaps in data about which parts of the country may be more vulnerable to an escalation of violence. It will be important to continually take stock of the risks, track abuses of power and instances of violence in real-time, and develop a strategy for sharing that information widely not only within the movement but with the media and general public.

Fourth, strengthening solidarity and preparing for a sustained struggle would help movements maintain resilience in the event of a November shock. If labor boycotts and general strikes are necessary to defend the vote and prevent large-scale violence people will need safety and financial security. Practically, this means reinforcing the community support and mutual aid networks that have emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic. Communities should be prepared to address paramilitaries in the streets and agent provocateurs itching for a race war. This means engaging strong community organizers and organizations, such as those that protected communities from police violence and opportunist attacks in Minneapolis.

Fifth, preparing for what follows the election, and addressing the dangerous polarization and intolerance that is afflicting both ends of the political spectrum, is critical for the longer term. Years of Black-led organizing and movement-building paved the way to a dramatic shift in public opinion about police brutality and Blacks Lives Matter, with widespread protests happening in small towns across America. Building from this example and investing in spaces for dialogue and organizing around issues that could engage the broader middle segment of Americans should be a focus beyond November.

As the country prepares for a momentous election, now is a good time for movement leaders, scholars, lawyers, and analysts to come together and start planning for any November challenges—including extra-constitutional ones—and prepare for the long, hard work of healing the country in the election’s aftermath.

Maria J. Stephan is the co-author of Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict and co-editor of Is Authoritarianism Staging a Comeback? Erica Chenoweth is the Berthold Beitz Professor in Human Rights and International Affairs at Harvard Kennedy School and a Susan S. and Kenneth L. Wallach Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. Candace Rondeaux is a Professor of Practice in the School of Politics and Global Studies at Arizona State University and a Senior Fellow with the Center on the Future of War, a joint initiative of ASU and New America. Follow them on Twitter: @MariaJStephan, @CandaceRondeaux, @EricaChenoweth.