By Juan Tellez, and guest contributor David Dow

The COVID-19 pandemic brought a brief respite in national deportation arrests in the US, yet two recent developments point to a likely increase in deportations in the coming year. The New York Times recently reported an increase in the number of immigration ‘sweeps’ since July, despite widespread concern about the potential for deportation-induced spread of the novel coronavirus to recipient countries. And just this week a federal court upheld President Trump’s decision to end Temporary Protection Status for approximately 400,000 immigrants, leaving them vulnerable to deportation in the coming year.

Despite the prevalence of deportation as a tool of governance in the United States—and the consequences that trend holds for Latin America—very little is known about the impact of deportation on the deportees themselves, what deportees leave behind when they are suddenly forced to leave their homes, and what they face in their new arrival communities.

As a first step to shed light on these questions, we are working with coauthors in the DevLab at Duke University, RTI International, and Te Conecta, a Guatemalan NGO, to collect data on the experiences of people recently deported from the US to Guatemala. We worked with RTI International to conduct field surveys at the point of entry, and then again at one-month and six-month intervals from arrival to understand how the lives of deportees had changed over time. Here’s what we found.

ARRIVAL

The most common arrival point for individual deportees in Guatemala is the Air Force airport in Guatemala City. The sheer number of deportees arriving in the city at any one time can be staggering: at the time of our survey, we observed 3 to 5 plane-loads of deportees arriving 4 to 5 days out of the week. Once on the ground, deportees are given little more attention than regular travelers: their entry into the country is processed at the airport and within hours they are out in the street to fend for themselves. Where to go from there is a daunting and overwhelming process. Based on our fieldwork, we noted that only a few deportees had family or acquaintances waiting for them upon exit; many simply took buses or taxis directly from the airport to their next destination.

THE EXPERIENCE OF MIGRATION

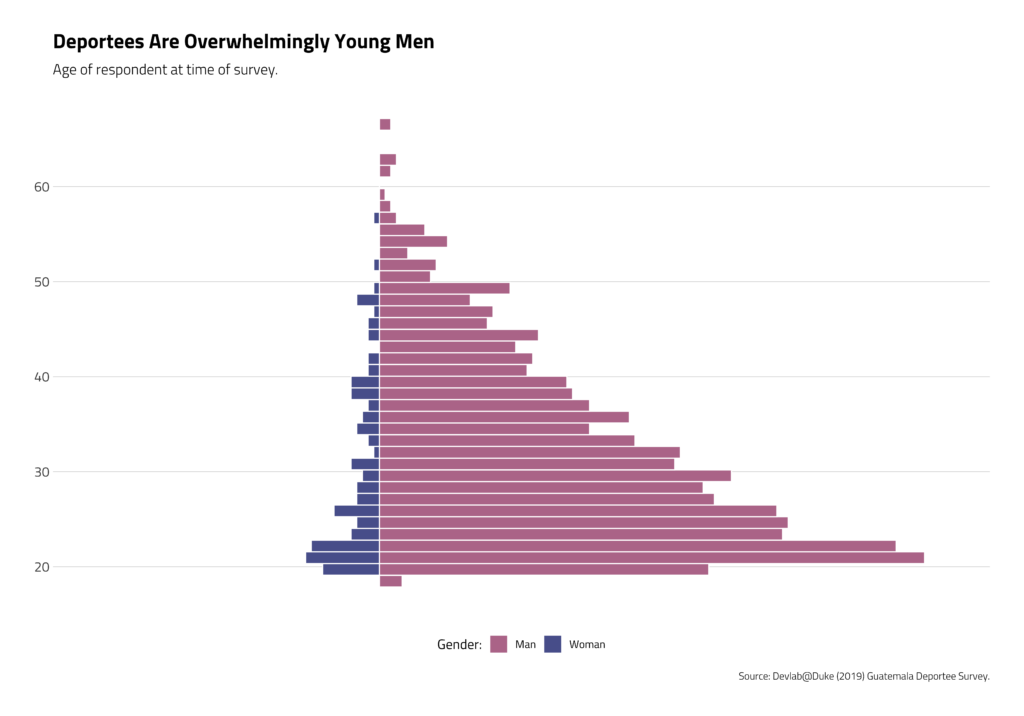

Overall, the deportees in our sample are overwhelmingly young men, a majority of whom are under the age of 30. The gender disparity likely reflects differences in broader deportation rates—roughly 9 out of 10 people deported by ICE (US Immigration and Customs Enforcement) are men—but also that men and women are processed differently upon arrival at Guatemala City.

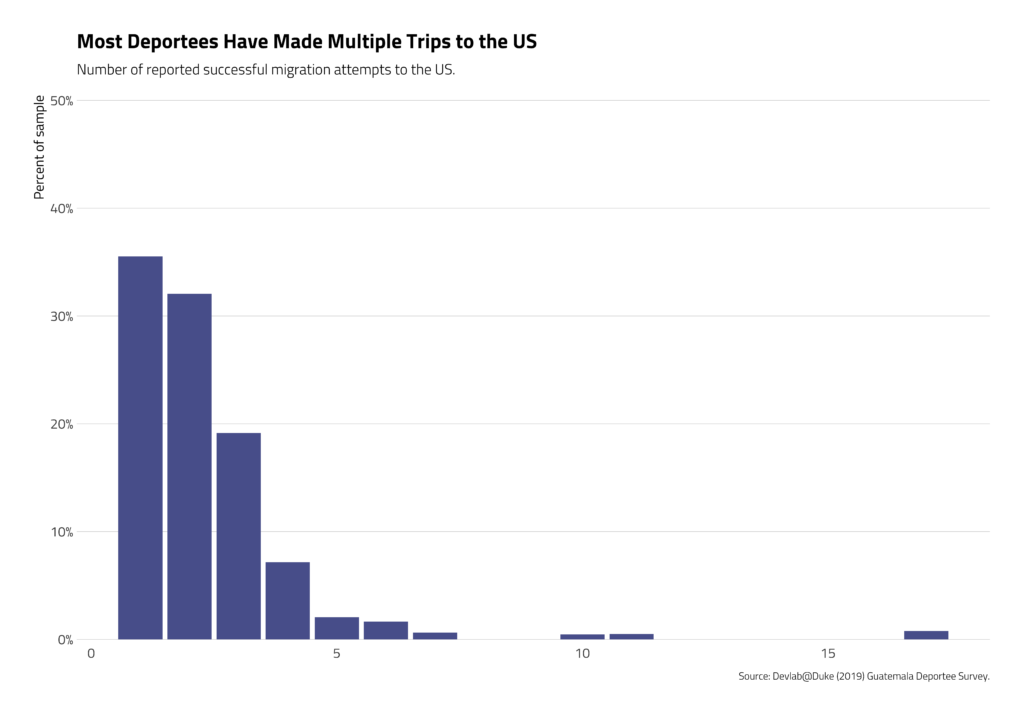

A majority of the people we spoke with report having made multiple migrations to the United States before they were arrested and deported. This pattern likely reflects the cyclical nature of employment for migrant communities, but is also surprising given the potentially large costs and risks associated with migration.

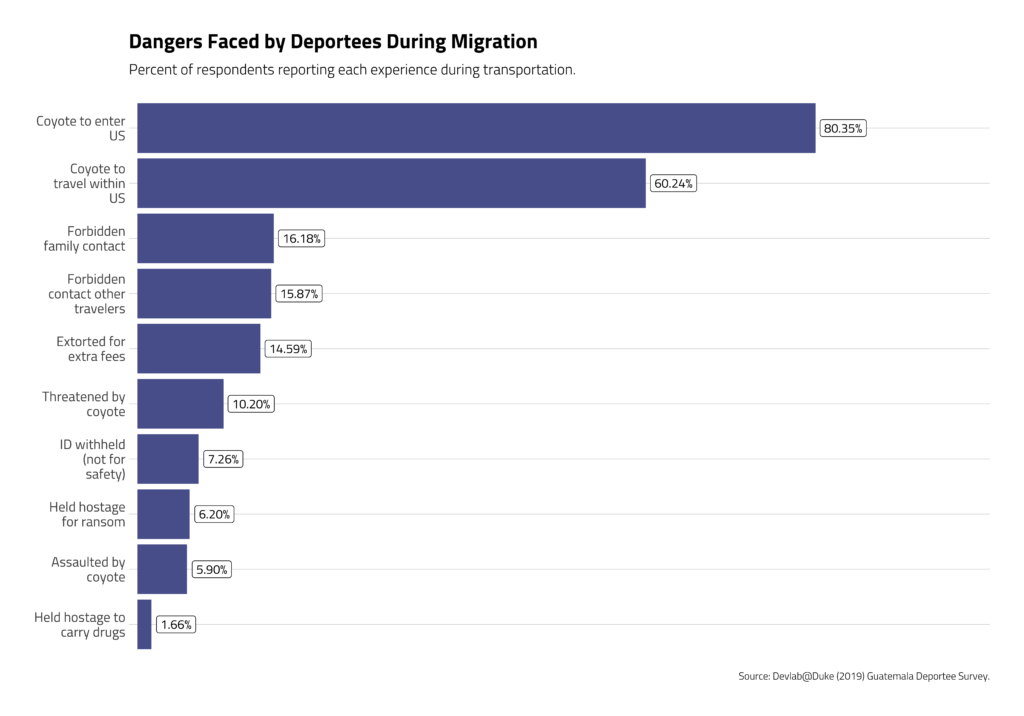

These risks are substantial. Eighty percent of the people we interviewed report relying on a coyote—a person paid to ‘smuggle’ migrants into the US—to enter the US and, once inside, about 60 percent report relying on one to travel within the US to their intended destination. Relying on a coyote can put migrants at risk of violence or extortion, especially the most vulnerable. The people we spoke with illustrate some of these dangers: almost 1 in 6, for example, report being extorted for extra fees that were not agreed upon prior to departure.

LEFT BEHIND

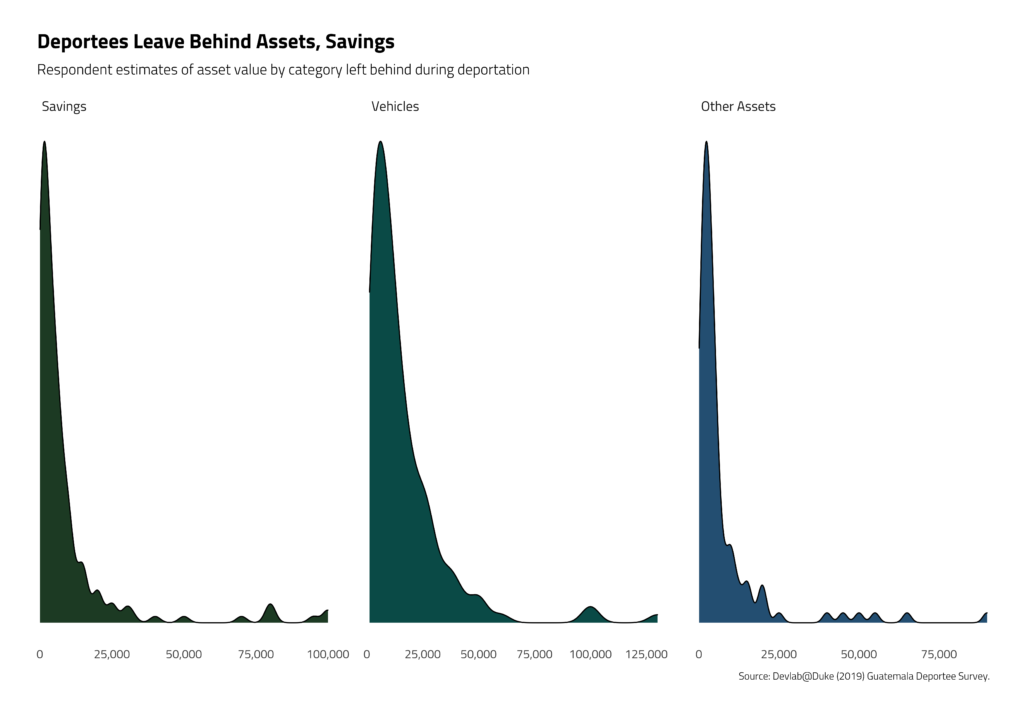

Once deported, many migrants leave family, friends, and other loved ones behind in the US. According to our data, 21 percent of respondents report leaving behind at least one child in the US—a devastating loss for deportees and their families. Many also leave behind life savings, cars, and other assets, which may represent years of accumulated work in the US.

Once in Guatemala, deportees face a range of conditions in their new arrival communities. Those who migrated to the US when they were young are often in danger in new communities they do not know how to navigate. Those who return to Guatemala with tattoos—unrelated to gang activity, and simply popular in the US—can face discrimination or targeting by gangs and police.

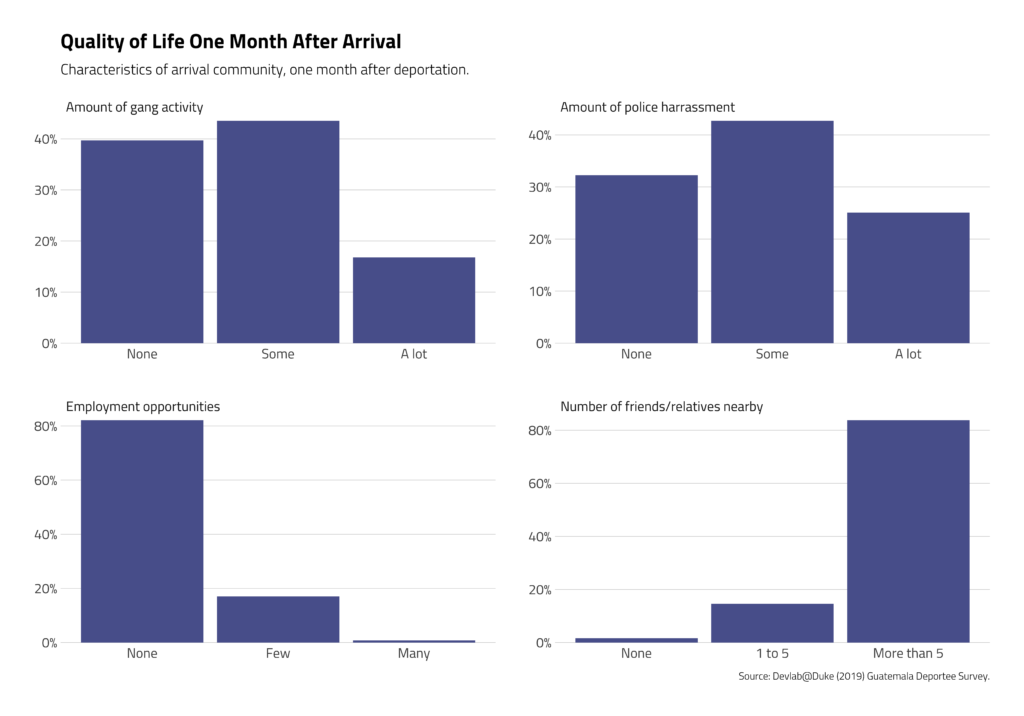

Our follow-up survey one month after arrival in Guatemala paints a bleak picture. A majority of respondents report some level of gang activity and police harassment in their new neighborhoods, with few local employment opportunities. Respondents do, however, report living near family or friends, suggesting that this is likely a big factor in determining where people move once arrived.

Grim prospects in Guatemala, in addition to the trauma of leaving family and precious resources behind during deportation, likely create a strong pull among deportees for attempting to re-enter the US. Indeed, roughly 40 percent of the people we spoke with in our initial survey willingly reported—within hours of arriving in Guatemala—that they had intentions of returning to the US. At the one-month follow-up survey, that proportion was even higher: nearly 60 percent.

THE BOTTOM LINE

In some respects, our data help clarify common deportee experiences and challenges. Many of the patterns we identify mirror depictions of the lives of deportees and those at risk of deportation offered by journalists, activists, and non-governmental organizations—and the experiences we outline here likely ring true for many Latin Americans who have been deported from the United States. Yet they also raise many more questions. Key among them are how deportees decide where to go upon arrival; how they navigate physical and economic security in their arrival community; and how deportees decide whether—and when—to attempt re-entry in the US.

Many of these decisions may well depend on the trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic and government responses to COVID in the US and Latin America. A weakened US economy may reduce incentives to migrate, yet deportees will evaluate these prospects relative to life in their current communities, which have also been economically devastated by COVID. Whether the upcoming US election results in a change of administration—and whether the new administration reforms deportation policy—will also have a big impact on the decision-making of those at risk of deportation.