Guest post by Ragnhild Nordås, Dara Kay Cohen, Robert Nagel

Tomorrow is the 20th anniversary of the groundbreaking UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women Peace and Security (WPS). Where are we on the road to ending conflict-related sexual violence? There is good news and bad news.

When the UN Security Council passed resolution 1325 on Women Peace and Security it was a momentous event. Women’s rights and violence against women had never before been on the agenda of the Security Council. Resolution 1325 emphasized the need for increased participation of women in national, regional, and international institutions, and for women’s inclusion in peace negotiations. Perhaps even more importantly, it acknowledged the agency of women in matters of war and peace, in contrast to the predominant idea of women as merely passive victims. A central component of 1325 was to explicitly call on all parties to armed conflict to take special measures to protect women and girls from violence, particularly sexual and gender-based violence.

As we mark the 20th anniversary of this resolution, it is time to ask: have we made toward accomplishing the goals of 1325 with respect to wartime sexual violence? The answer is both yes and no.

The Good News: A Revolution in Research

One reason to celebrate is the enormous advances in knowledge production on the topics of sexual and gender-based violence in the last 20 years. The introduction of sexual violence as a subject worthy of serious theoretical and empirical study, in political science in particular, has helped overcome the problematic historical neglect of gender issues in conflict studies.

UNSCR 1325 and its nine follow-up resolutions encouraged more systematic analyses and data collection—and research on wartime sexual violence has grown substantially as a result. One illustration of this growth are citations: from being a topic that generated only 288 social science citations in 2000, there were a staggering 4,397 citations in 2019, according to Web of Science.

Thanks to scholars, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers around the world, there is a veritable revolution in research underway. These efforts have generated critical theoretical and empirical insights. While sexual violence was once considered a ubiquitous feature of war, we now know that it varies a great deal across time and space. For example, there are well-documented cases of armed organizations that have never been reported as perpetrators of sexual violence, even within the context of mass rape wars.

This important variation has prompted scholars to study armed groups as the key unit of analysis and to examine the conditions under which armed groups are most likely to perpetrate sexual violence. Ideological groups, groups that invest in political training, and organizations that elect their leaders through a democratic process are less frequently reported as perpetrators. On the other hand, groups that use forced recruitment and child soldiers, and those that extort producers of natural resources, are more likely to be reported as perpetrators.

Overall, organizational characteristics and group dynamics have more analytical power to explain variation than ideas about unbridled male sexual urges or primordial ethnic hatreds, which dominated the earlier understanding of conflict-related sexual violence. (Although most acknowledge that sexual violence is not about sex but about power/violence, others have made important recent critiques of this framing.)

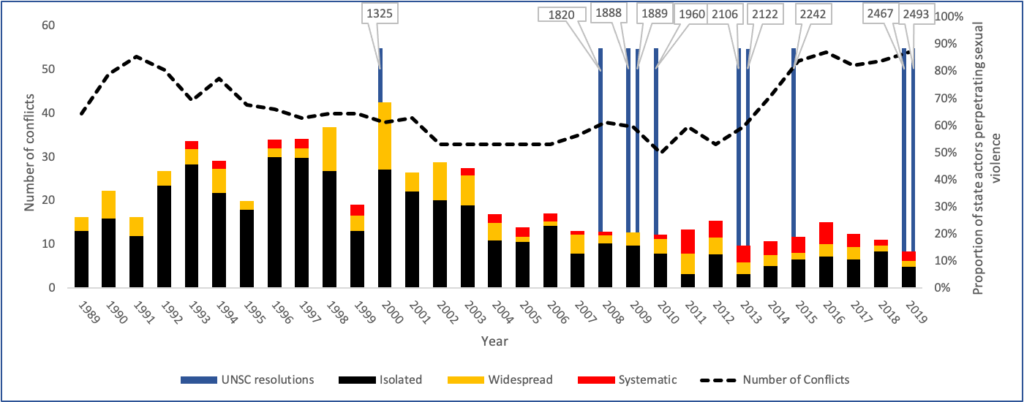

Further, scholars have documented that states are the most frequently reported perpetrators of sexual violence. Even where rebel groups and militias show restraint, state forces often perpetrate sexual violence against civilians. The Sexual Violence in Armed Conflict (SVAC) dataset records that the highest share of state actors reported as perpetrators of sexual violence in war occurred in the year 2000, the year that 1325 was passed. That year, 69 percent of all active states at war (or 22 out of 32) were reported as perpetrators of some level of conflict-related sexual violence.

On this important anniversary, it is worth celebrating this rapidly expanding research field, which provides a corrective to widespread conventional wisdom, and a solid evidence-based foundation for policy that did not exist two decades ago. All of these findings are useful for policymakers, and can be leveraged to understand where hotspots are most likely.

The Bad News: Violence Is Still Widespread

A landmark event in the fight against wartime sexual violence was in 2018, when the Nobel Peace Prize went to Nadia Murad and Denis Mukwege, two champions for sexual violence survivors, who have fought to bring attention to the issue and remedy the situation for survivors. However, two years later, sexual violence remains a major issue in many conflicts. ISIS still holds Yazidis in sexual slavery, and reports of Myanmar’s military committing brutal mass rapes of the Rohingya continue.

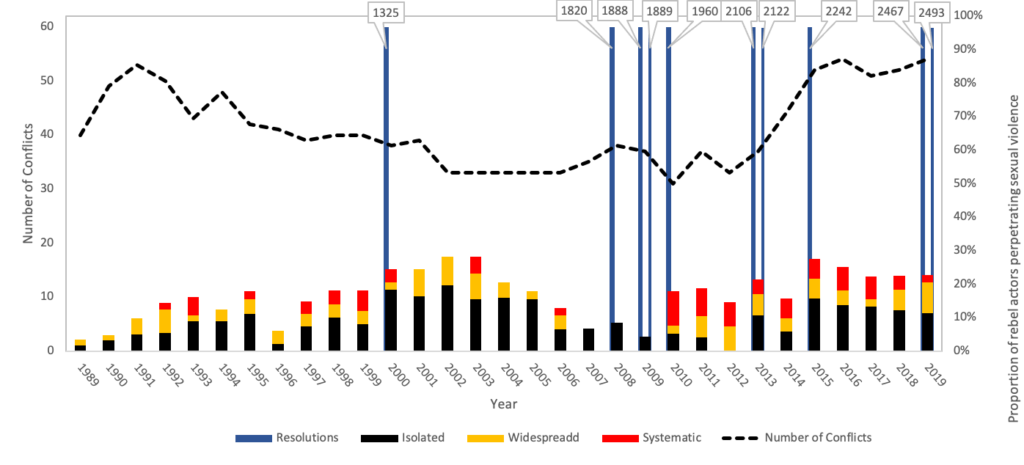

Despite the passage of 10 Security Council resolutions, a new update of the SVAC data show that, in 2019, states are also still frequent perpetrators; out of the 55 states that were primary parties in armed conflict, 10 were reported to commit sexual violence. However, we see a slight decline over time in states reported as perpetrators (Fig. 1). We also see that nearly a quarter of rebel groups involved in armed conflict were reported to commit sexual violence, most of them at widespread or systematic levels. The higher share of cases of reports of large-scale sexual violence by rebel groups in the last few years, suggesting a turn for the worse.

A Light in the Darkness

One beacon of hope is survivors and their allies, who increasingly speak up about what happened to them, and who are resilient in the face of trauma and social stigma. In many conflict and post-conflict contexts around the world, survivors are turning pain into power, developing strategies to counteract stigma and exclusion, and mobilize against sexual violence.

Even during periods when the UN Security Council has been divided, it has repeatedly come together to address conflict-related sexual violence. Despite worrying signs in recent years and even days, we hope this will continue. Following the adoption of UNSCR 1325, UN peacekeeping mandates are more likely to be gender mainstreamed, especially when conflicts involve sexual violence. The Security Council is also more likely to address conflicts in a resolution and to send peacekeeping missions when there are reports of sexual violence in a conflict. Yet, there is still much more the Security Council could do, such as consistent and comprehensive sanctions in response to wartime sexual violence, and holding firm on existing commitments.

On this 20th anniversary of the UNSCR 1325, sexual violence is no longer seen as inexplicable and inevitable. Now it is time to leverage this knowledge for prevention and mitigation.

Ragnhild Nordås is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan. Dara Kay Cohen is a Ford Foundation Associate Professor of Public Policy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. Robert Nagel is a postdoctoral fellow at the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security.