Guest post by Megan Turnbull

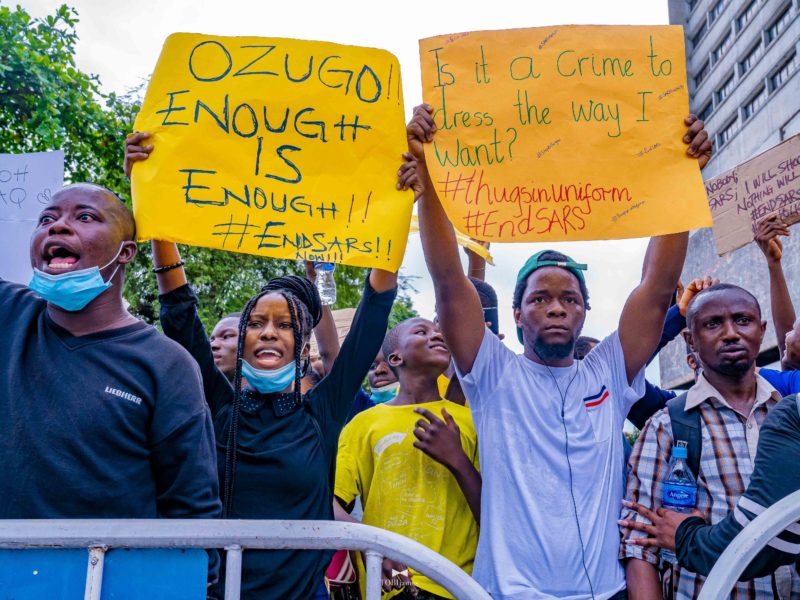

Police brutality is an entrenched problem in Nigeria and the US, and 2020 has seen protests against police violence in both countries. On the surface, protesters’ demands seem nearly identical. The hashtag #EndSARS—in reference to the Nigerian police unit, the Special Anti-Robbery Squad—sounds similar to calls to abolish or defund the police in the US. Yet a closer look reveals important differences.

Most Nigerians do not extend the demand to disband SARS to other police units; in fact, many have called for more and better policing—not less. In the US, on the other hand, activists have called for less policing and reallocating funding for the police to other social services, a position that is gaining traction among the American public.

Why do Nigerians and Americans have different demands for a seemingly similar problem?

In Nigeria, police brutality is widely understood as part and parcel of the larger problem of corruption, and demands for more and better policing parallel earlier popular efforts in the north, southeast, and the oil-rich Niger Delta, for greater government presence that is accountable, transparent, and responsive to citizens. In contrast, in the US, scholars argue that the police serve to uphold a racialized political order and deny participation in democratic governance to people of color, and Black communities in particular. Calls to abolish or defund the police are part of a larger effort to dismantle white supremacy.

In Nigeria, encounters with police brutality, extortion, and violence are not unique to any one indigenous or religious group in Nigeria; rather, such experiences are common across the population. The Centre for Law Enforcement Education, or CLEEN, which was established in 1998, has meticulously reported on police abuse and suggested concrete reforms; and academics have written extensively on the colonial origins and current problems of policing. The recent EndSARS campaign, which began in 2017, includes a broader set of demands to reform the police: investigating allegations of abuse and corruption, holding officers accountable for human rights abuses and civil liberties violations, compensation for the families of those killed by police officers, retraining, reforming, and redeploying officers, and increased pay for police officers. These demands parallel efforts to rein in corruption and enhance the capacity and responsiveness of the Nigerian government.

Encounters with the police differ dramatically by race and ethnicity in the US. According to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation poll, 21 percent of Black adults report experiencing police violence because of their race, compared to 8 percent of Hispanics and 3 percent of Whites. Similarly, 41 percent of Black adults report being stopped or detained by the police, compared to 16 percent of Hispanics and 5 percent of Whites. The police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio; Walter Scott in North Charleston, South Carolina; Philando Castile in St. Anthony, Minnesota; Lacquan McDonald in Chicago, Illinois; Eric Garner in New York, New York; Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Maryland; George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, powerfully illustrate that Black people are far more likely to be killed by the police.

Scholars have shown that the problem of police violence in the US is not a problem of corruption, as in Nigeria, but of a racialized political order that upholds white supremacy and differentiated citizenship with violence and intimidation. Existing research argues that policing and the larger criminal justice system help to maintain a racialized caste system that blocks Black communities and other communities of color from participation and representation in government, affordable housing, education and employment opportunities, and other essential services. Because the police serve as the “guardians of white democracy,” calls to abolish the police, or defund them as a long-term effort toward abolition, are advanced by some as part of a larger project of racial equality.

Interestingly, there is a history of police corruption in the US, and policing in Nigeria has its origins in British colonial rule and white supremacy, but the core of police violence today and protesters’ demands differ in important ways between these two countries.

In terms of policy implications, the comparison of protests in Nigeria and the US highlights the importance of context for tackling entrenched societal problems. Neither police violence nor protests against police violence are unique to either of these countries, but the roots of police violence, and how it is differently experienced by identity groups, differ in important ways across countries that carry implications for ending police brutality. In Nigeria, reducing police violence means reining in corruption, enhancing accountability and transparency, and ensuring that public funds are invested in hiring more, better trained, and better-paid police officers. In the US, where the police have been heavily militarized and face no shortage of resources, ending police brutality entails dismantling white supremacy and the racialized political order that supports it. Calls to abolish or defund the police as well as other reforms are put forth with this overarching goal in mind.

Megan Turnbull is an assistant professor in the Department of International Affairs and a Faculty Fellow with the Center for International Trade and Security at the University of Georgia.