By Dawn Brancati and guest contributors Jóhanna Birnir and Qutaiba Idlbi

Prior to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) was nearing collapse. At the close of 2019, ISIS had lost control of all its territory and was half the size it was at its apex. As the pandemic overwhelmed Europe and the United States, ISIS pledged to exploit Western and regional vulnerabilities to rebuild. Calling COVID-19 “the smallest soldier of God,” ISIS urged its followers to capitalize on the free fall of Western economies to escalate attacks.

ISIS’s threats have provoked fears among government and security officials and policy experts in the region and abroad. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, said that the effect of COVID-19 on ISIS is a “ticking time-bomb that must not be ignored.”

Did the COVID-19 pandemic strengthen ISIS? To evaluate the threat, in new research, we analyzed the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of violent events—e.g., explosions, battles, and armed clashes—initiated by ISIS in its strongholds in Iraq, Syria, and Egypt over a 78-week period. The analysis is based on data from ACLED, as well as original data on the pandemic compiled from local news sources and reports.

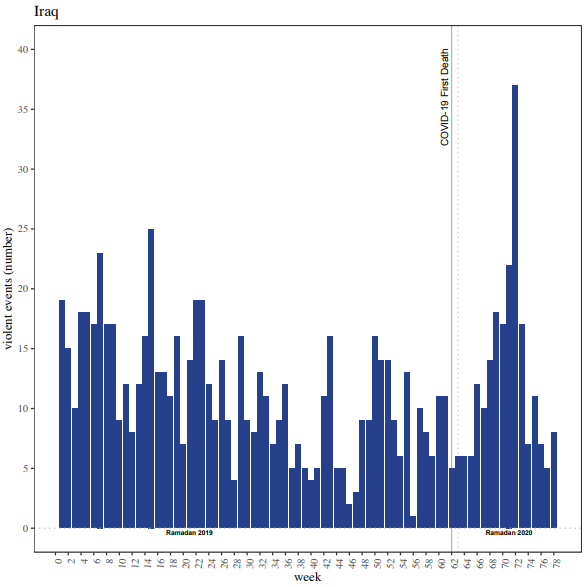

We find that, by and large, ISIS’s threats have not come to pass. Only in Iraq, where ISIS has the largest physical presence and where the US has troops on the ground, do we find evidence of an increase in violence. Figure 1 depicts the number of violent events initiated by ISIS in the weeks leading up to and following Iraq’s first death from COVID-19. As the graph makes clear, there was a sharp increase in the number of attacks by ISIS soon after Iraq’s first death from the virus.

Figure 1

To disentangle the effects of COVID-19 from other factors that coincided with the pandemic, such as Ramadan and a decline in oil prices—which could in theory help ISIS by reducing the revenue available to the government to fight them—we conducted a statistical analysis of the pandemic’s relationship to the number of violent events initiated by ISIS. The statistical analysis confirms that in Iraq, the pandemic is associated with a significant increase in the number of ISIS-initiated violent events. This increased violence cannot be explained by Ramadan—during which ISIS has previously pledged to increase attacks—or the concurrent decline in oil prices.

But what specifically about the pandemic drove the increase in violence? We believe that the increase in violence in Iraq is most likely due to the social distancing measures that Iraqi and US forces undertook to protect against the spread of COVID-19 among their forces. The Iraqi military sub-divided its units into small cell-like groups, halved the number of personnel on duty, and reassigned some forces to enforce curfews and travel bans to protect its soldiers from disease. The US greatly scaled back its activities as well. US forces stopped accompanying Iraqi units on missions and expedited plans to shut down their military bases, among other things. These measures likely gave ISIS the room it needed to plan and execute new attacks. Neither Syria nor Egypt undertook any similar measures. (None of the three countries reduced military spending in this period despite the financial strains of the pandemic.)

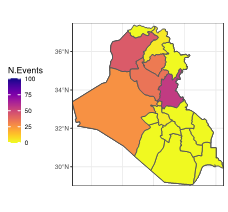

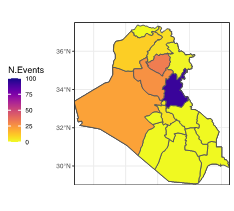

All roads do not lead to Baghdad, however. Other aspects of the pandemic have worked against ISIS, namely the lockdown measures—curfews and travel bans—that governments have imposed to prevent the spread of COVID-19 among the general population. According to our statistical analysis, these measures not only reduced the overall number of ISIS attacks, but also altered their location (i.e., rural/urban) and dispersion. Curfews, we hypothesize, displace attacks away from urban areas because they leave fighters more exposed in these areas than in sparsely populated ones. Internal travel restrictions lead to a concentration of attacks within northern Iraq, by making it logistically more difficult for fighters to execute attacks outside of where they reside. Figure 2 illustrates, for the analysis period, the changes in the concentration of attacks in Iraq when travel bans are in place and when they are not.

Figure 2

The future of the US position in Iraq under the Biden administration is in a state of flux. The US plans to shift its capabilities toward training and advising and to redeploy its combat troops outside Iraq. The timing of this change is yet to be determined, but when it does occur, ISIS will have even less to contain it, pandemic or not. Although the Taliban is stronger than ISIS, the recent upsurge in violence in Afghanistan following the US’s announced pullout of combat troops from the country, leaving only NATO forces to train Afghan forces fighting the Taliban, is telling of the substantial risk that the US’s current plans pose for Iraq.

Dawn Brancati is Senior Lecturer at the Jackson Institute at Yale University. Jóhanna K. Birnir is Professor in the Department of Government and Politics (GVPT) and Director of GVPT Global Learning at the University of Maryland, College Park. Qutaiba Idlbi is Non-Resident Scholar at the Middle East Institute and Representative to the United States for the National Coalition for Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces.