IGCC Dissertation Fellow Series

Guest post by Mariana Carvalho

The 2018 murder of Rio de Janeiro’s local councilor Marielle Franco thrust the topic of political assassinations into the international spotlight (see here and here). Over the last municipal election year in 2020, at least 82 politicians and candidates were assassinated in Brazil, according to Center for Security and Citizenship Studies. Mexico also recently observed one of its most violent elections, with 89 politicians killed since September 2020, according to the security consulting firm Etellekt. While high-profile assassinations of state leaders may seem like rare events, the execution of local politicians is a frequent phenomenon in several countries, and not restricted to elections.

What are the possible causes of violence against local politicians? And what can be done to stop the violence?

Answering these questions requires data on political assassinations. But information about different types of violence remains scarce in many places around the globe. Researchers have worked to build datasets documenting acts of violence such as the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) and the Correlates of War Project (COW), which have enabled researchers to situate violent events geographically and study variation both within and across countries. Nevertheless, newspapers are better at picking up violent events in urban areas and historic hotspots. But the media often underreports events of political violence, overreporting dramatic events relative to more mundane violence that is less sensational but often more prevalent. Information from the media can reveal important patterns, but can lack details that show the real magnitude of the phenomenon.

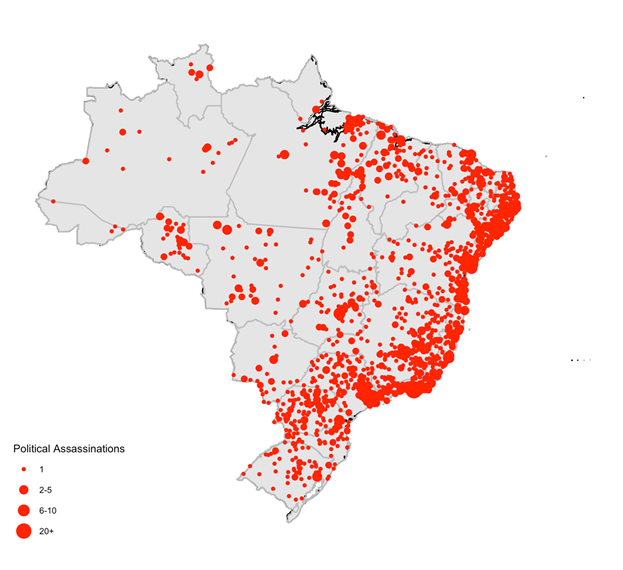

To overcome this lack of information, I constructed an innovative dataset using official statistics on violent deaths in Brazil. By linking this dataset to information about all Brazilians who have run for political office, I was able to identify the universe of candidates and elected politicians who were executed between 2001 and 2017. In total, 2,241 local politicians, mayors, and local councilors were assassinated—a stunning and startling number.

The map of Brazil shows that assassinations are the norm in local politics—not an outlier. Virtually no region of this vast country has escaped this form of violence. And assassinations are not restricted to dense urban centers or zones most affected by poverty—they are dispersed across the country. This surprising frequency makes the lack of media and academic attention to the subject puzzling.

What is driving the violence? Violence is often used to influence election results, especially in countries with weak democratic institutions where there are abundant opportunities for state capture and corruption. But in Brazil, most assassinations are not happening only during elections, and Brazil historically has a strong electoral system. So what’s going on?

The answer centers on politics and corruption. In Brazil, municipalities receive large federal transfers and have considerable control over how to allocate resources. Political office often means access to those resources, plus an extensive clientelist and patronage network. Corrupt officials can take advantage of these resources for their own enrichment—and have a strong incentive to protect their corrupt contracts. That’s where violence comes in. In Brazil, we see political violence being used, not only to influence electoral results, but to solve political disputes over control of the spoils associated with administrative control of the state. A windfall of resources is more likely to lead to political violence, since higher revenues induce more corruption because politicians have more room to grab rents and attract lower-quality candidates. Violence can be used, therefore, not only as a way to manipulate elections, but to enforce corrupt contracts.

If corruption directly affects the likelihood of assassinations, what policies might curb corruption, and thereby reduce political assassinations? The central government, which has limited oversight of local officials, launched an anticorruption program in 2003 to prevent and investigate the misuse of public funds. The program selects municipalities randomly via public lottery. Audit results have shown that they reduce corruption, make officials more accountable to voters, and are most effective where there is a state apparatus with jurisdiction to enforce legal actions.

Government audits might reduce corruption, but do they also reduce violence against local politicians? The answer is: yes. Once a municipality is audited for corruption, political assassinations decrease. The audit unsurprisingly has a stronger effect in reducing violence in places with more resources.

The current wave of political violence is troubling. As state actors become not only the perpetrators but also victims of violence, election-related violence becomes a broader issue that extends beyond campaign periods. Many studies have shown how political coercion can be used to influence turnout and voting behavior (see here, here, and here), but the case of Brazil shows that violence can also be used against candidates and elected politicians to perpetuate one’s political and economic power and access to the perks of office. But Brazil also shows that there are policies that can help. Anti-corruption programs have the potential to reduce political assassinations, in Brazil and other places where corruption is a key driver of political violence.

Mariana Carvalho is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of California, San Diego and a 2020–2021 Dissertation Fellow at the UC Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation.

Don’t have time to read the article? Listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.