For every conflict—whether in Afghanistan, Gaza, or Yemen—there are hundreds, if not thousands, of people who experience hardship, loss, and trauma. Here, researchers and practitioners from political science, psychology, neuroscience, and public health share their thoughts on what trauma is, how trauma from political violence is similar (and different) from trauma caused by other things, the relationship between trauma and justice, and what it means to recover from mass trauma in the context of COVID-19.

Years ago, the World Bank put out a great volume on how financial shocks affect development at various stages of life. Much of my work on youth and violence extrapolated from that text, with the assumption that violence shocks would affect youth similarly as economic shocks—in terms of cognitive function (e.g., ability to focus in school, and the long-term ramifications of that) and in terms of relationships (i.e., ability to manage negative emotions). However, we are starting to learn how economic stresses differ from the stress and trauma that arise from being exposed to violence. For example, in a study of Syrian refugees in Jordan, economic stresses were found to be more related to deficits in working memory than symptoms of PTSD. It is likely the constant stress of meeting basic needs is understandably distracting, making it difficult for people to focus. Continued research understanding how these different forms of stress affect cognitive and social processes would help us better target interventions.

Of course, as Rose McDermott eloquently states, it is often hard to disentangle these stresses in wartime. In addition to direct exposure to violence, war and conflict devastate economies, families are displaced, relatives are recruited to fight. These sources of stress also interact. When I was in northeastern Nigeria, many women talked about watching their houses being burnt to the ground. The violence that they were exposed to also displaced them and left them without a home. The violence and economic stress were inextricably linked. As a result, it will be hard to isolate the differences between these various forms of stresses in many cases.

Additionally, in these conflicts, there are layers of uncertainty that contribute to a great deal of psychological stress—when will the violence end, when can I go home, do I have a home, will I be able to feed my family—and the prolonged nature of that stress and uncertainty is acutely damaging to well-being. This leads me to a lesson I learned in Afghanistan that is relevant to researchers and practitioners. Colleagues had gone to Badakhshan, a more isolated area of Afghanistan, where at least in those days, there were fewer security risks. They couldn’t believe how freer their minds were, how creative they could be, when they were there. They realized that security had become this background noise in their lives that had them constantly distracted. It was an important reminder of the stress my Afghan colleagues were under—the economic and physical insecurity in their daily lives. And how I needed to be more sensitive to that when working in conflict zones—with the staff and enumerators and their ability to focus on tasks, with designing research that participants could engage in, and with designing interventions and related results that considered the stresses in participants’ lives.

Dr. Rebecca J. Wolfe is a leading expert on political violence, conflict and violent extremism. She is a senior lecturer at the Harris School for Public Policy at the University of Chicago, where she also is an associate at the Pearson Institute for the Study and Resolution of Global Conflicts.

Political violence, like many other traumatic circumstances, is defined by its effect on individual people as well as its collective impact. What makes political violence traumatic is it not only creates hardship for the victims, but also disrupts their sense of a predictable, orderly, or controllable world, and one where there is benevolence and trustworthiness. These core beliefs or assumptions lead to anxiety and confusion. But they can also be catalysts for change. For example, some people are compelled to act in opposition to the political violence. Whether they choose violent means themselves or seek to construct a more peaceful and just world involves many other factors. A reconstruction of the core belief system is crucial in determining what means are used to oppose the violence. It is also useful to consider what creates fertile ground for political violence and how people come to act in this way. It appears to be a circular system in which some group perceives injustice and lack of power, and is fearful of losing what they believe to be rightfully theirs. Such perceptions create a self-perpetuating cycle of grievance and aggression. Constructing belief systems that acknowledge universal human needs and how these can be met justly can go a long way toward putting an end to these cycles.

—Richard G. Tedeschi, PhD

Richard G. Tedeschi is the distinguished chair at the Boulder Crest Institute for Posttraumatic Growth.

Individuals and communities affected by a political violence can experience a wide range of emotional and psychological reactions. When people move, seeking a safe haven, it is wrongly assumed that they are suffering because of what happened to them in the past—usually regarded as past traumatic events. Although we cannot ignore the impact of the past experience, many displaced people are significantly distressed by their present circumstance and worries about the future. What people have to go through every day—like searching for food, health care, education for the kids, livelihood opportunities—can be serious and totally overwhelming concerns for people. The lack of certainty about the future and what may happen tomorrow is itself very distressing for people too.

Don’t assume that people are stuck in the past. No, the daily life stressors are their major concerns now. Provision of basic needs and support now is the best way to help them rather than focusing on past traumatic events. Scientific research has found that daily stressors mediate the impact of past trauma on mental wellbeing, so addressing these stressors is crucial in mitigating the impact of these traumatic events.

Mohamed Elshazly is a consultant psychiatrist for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

The popular image of trauma typically involves someone who has experienced rape or combat. But trauma is a much broader experience. Specifically, the effects of trauma are not necessarily limited to the person who experiences it directly. For example, people who lose friends to mass shootings may be traumatized by the loss even if they were not present at the shooting itself. The loss itself can be profound, but that loss can also shatter the person’s belief in their own personal safety and security.

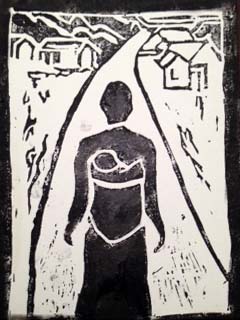

The one thing I wish people understood better about trauma is its intergenerational characteristic. Trauma can carry across generations, and not only because of the normal processes of socialization and culture that people experience in their households growing up. Trauma can be communicated biologically, through the in utero bath in which people gestate and develop as fetuses. The mother’s environment, whether it be one of abundance or deprivation, peace or war, confers information to her unborn child in ways that can affect genetic expression in that child across the course of their entire life. Mothers who are the victims of rape, are very young, or are pregnant under conditions of famine, drought or war offer a different developmental experience for their children than those who give birth under conditions of peace and security. That kind of intergenerational trauma can affect the child’s health, making them more susceptible to all kinds of disease and lowering their life expectancy. Interventions can help but people have to first recognize that those interventions are necessary to overcome trauma that children may not have experienced themselves, but that can nonetheless have huge impacts on their life through no fault of their own.

The other thing that is important for scholars to recognize about trauma is that they themselves, and their students and post-docs, can experience a kind of second-hand trauma from listening to traumatic stories that they hear as part of fieldwork or other forms of scholarly inquiry and investigation. Listening to horrific stories can exert its own kind of trauma on first responders, mental health professionals, and researchers alike. Scholars need to be aware of these effects and mindful about the kind of positions they place their students and postdocs in during research. Proper training can provide some protection but follow-up may also be necessary.

Trauma is often not a single event or experience. Rather it can accumulate across the course of life experience. But it can exert a profound impact on not only injured parties, but on those who love and care for them. In this way, trauma is a community experience that requires a broader community response to address its effects before they simply perpetuate across generations in never-ending replication and expansion.

Rose McDermott is the David and Marianna Fisher University Professor of International Relations at Brown University.

Political violence has to be contextualized and defined. There is political violence from an authoritarian regime as in Syria, and there is political violence from settler colonialism as in Palestine, with support from international parties. The lack of freedom and inability to turn to any higher authority of justice is trauma in its own right for Palestinians. Trauma in Palestine is continuous; it is not a one-time event or period. It has been going on for 75 years. Hence we need to redefine trauma to include the idea that for some it is a continuous experience. How does one cope, as the intensity of the trauma increases level by level? In circumstances like these, there is no standard definition of normal anymore. Because each normal is relative. Context is very important.

The trauma caused by not attaining justice is profound because there is nowhere to go and nothing to resort to. Thus it is continuous. New research is coming out that documents this reality. What we see on the ground is that when there is no justice people are angry—but this leads to the courage to do something to bring about justice, for example speaking out, protesting, fighting back.

Research in trauma theory and in mental health practice in Palestine has worked to develop distinct diagnostic criteria, methodological approaches, and therapeutic practice. What has emerged from this body of work is a clear sense of mental health ethics that situates the individual within the political context. As Dr. Samah Jabr, mental health unit chief in the Ramallah Ministry of Health, so clearly put it: it’s the situation that’s sick, not the individual. Existing frameworks pathologized the individual for what were in fact quite reasonable responses to untenable conditions. As a result, theory and practice in the Palestine context have focused on repair: revitalizing community bonds, developing language for talking about and recognizing the ongoing harms experienced, and creating what the Palestine Trauma Center in Gaza City calls “competent communities” where mental health is supported alongside other urgent and long-term needs.

Rana Dajani is Professor of Biology and Biotechnology at Hashemite University in Jordan, Founder and Director of We Love Reading, and President of the Society for Advancement of Science and Technology in the Arab World. Writing with Nora Parr, Alexander von Humboldt Fellow at the Freie Universität Berlin.

The global relevance of trauma is particularly acute today, as we are living through a mass trauma event: the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to think about how this trauma will impact us, not only as individuals, but as communities and nations. These past 18 months have been unlike any other in modern history. We have lost relatives and livelihoods, our connections to others, and how we share public space. We have lost our ability to mourn in traditional ways. We have had our sense of stability and control radically upended.

Throughout, we have had to consider not only how we are affected in the moment, but how this experience will remain with us going forward.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a collective trauma, one larger and more expansive than others in recent history. It has had numerous phases and encompassed the near entirety of our lives. As such, part of incorporating it into our narratives will be allowing for complexity in the way we remember.

What helps us move through trauma? Shared coping. Communal grief. Rituals. Commemoration. For much of the pandemic, collective grief in the US has been denied. Until President Biden took office, there was no federally organized public memorializing of the lives lost to COVID-19. Rather, the Trump administration repeatedly downplayed the severity of the loss in explicit terms. During this time, private citizens worked to coordinate tributes. Last fall, artist Suzanne Brennan Firstenberg installed 250,000 flags outside the DC Armory to mark the 250,000 people who had died in the US by that time.

President Biden, who has a well-documented history with grief and loss, has held the country’s pain in a different way since he entered office. The night before he was sworn in, he hosted a commemoration event for those who have passed. In March he held another, marking the horrific milestone of 500,000 dead. Private memorials have continued, as well; just last week, Firstenberg installed an updated memorial, this time planting 670,000 flags on the National Mall to mark 670,000 lives lost to COVID-19 in the US. The flags cover 20 acres and took 150 people three full days to install. More flags will be added each day to reflect the previous day’s death tolls.

Perhaps ironically, as we reopen and move further from the most acute phases of the pandemic, it is likely that our collective trauma will feel more tangible, not less. As we shift away from our screens and back into shared spaces, as we allow our bubbles to widen, we will have the ability to see our experiences of this time—the personal and the collective—with more perspective and through others’ eyes.

It might feel easier right now to shut our eyes and barrel full force into the future, opting to leave the feelings and memories of the past 18 months in the past. It may be that when we are able to make some space, that the full force of the trauma and grief will hit us—that when we are able to have some of the day-to-day fear and stress alleviated, we will have to stand face-to-face with the pain we have held at bay in order to survive.

—Biz Herman, Justine Davis, and Cecilia Hyunjung Mo

Biz Herman is a PhD candidate in political science at the University of California, Berkeley. Justine Davis is an LSA Collegiate Fellow in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan. Cecilia Hyunjung Mo is the Judith E. Gruber Associate Professor of Political Science at University of California, Berkeley.

Learn more: Tune in to the Talking Policy podcast, and don’t miss the episode on the Psychological Consequences of Conflict. Talking Policy is a podcast of the UC Institute on Conflict and Cooperation, a sponsor of Political Violence At A Glance.