Guest post by Martín Macías Medellín, Mauricio Rivera, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch

Mobilization in autocracies is inherently difficult. Potential dissidents face several hurdles, even when grievances are widespread and a regime is unpopular. Participating in dissent is dangerous and leaves individuals at risk of repression by state security forces. Safety in numbers is possible if others also mobilize, but in autocracies people often lack information about what others think and what they are going to do.

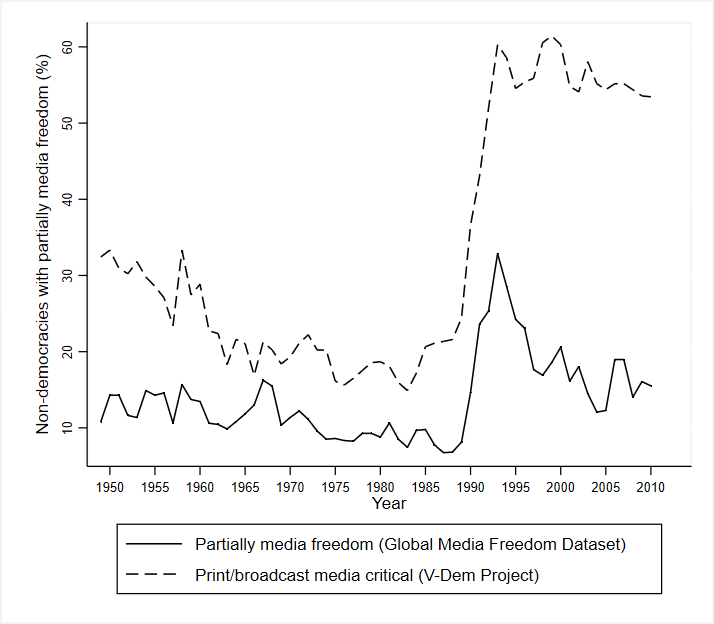

In a recent article, we show how even partial media freedom can make a major difference to nonviolent mobilization in autocracies. It is often assumed that media freedom is limited to democracies, and that autocratic regimes fully control the media and suppress independent information. But many autocracies have some degree of media freedom, and many news sources are not fully controlled by the authorities (see Figure). The editor of the independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, for example, was awarded the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize for efforts to safeguard freedom of expression. Moreover, the number of nondemocracies with partially free mass media has increased notably since the end of the Cold War.

Source: Global Media Freedom Data set and the Varieties of Democracy project.

Even partial media freedom can provide important help for dissidents, since independent media can help convey information that makes mobilizing easier. On the one hand, independent media can provide information about the nature of a regime and salient policy failures, helping to mobilize mass public opinion against a regime. It can raise awareness about what others believe, and help calibrate expectations about how likely it is that dissent will attract broad support and active participation. It can make it easier to coordinate a course of action if, for example, protest strategies can be advertised and disseminated broadly. Media freedom can also help provide dissidents with important information about the regime’s opponent. Coverage can help illuminate specific bases of regime support that are more—or less—likely to be influenced by protest and opposition, which can, in turn, help movements evaluate what types of strategies to use.

These aren’t just conjectures. Our research shows there are substantially more uprisings in autocracies with partial media freedom. Moreover, anti-government protests in one country have a tendency to encourage mobilization in others—especially when the other countries have partial media freedom. Although dictators may allow some media freedom because it can help them gain insights into the opposition and potentially better adjust to challenges, our results show that media freedom is a double-edged sword, since even partially free media outlets can facilitate nonviolent dissident mobilization, which itself can promote democratization.

What type of media has the biggest impact? Although much of the recent interest in technology and political mobilization has focused on the internet and social media, journalists and traditional media outlets often have greater reach, especially when internet penetration is low. And by presenting a more coherent framing of events they can have a larger influence than on-off individual pieces on social media. During the Georgian rose revolution, for example, the television channel Rustavi-2 helped to disseminate information about corruption in the Shevardanze regime, and mobilized support for the opposition by spotlighting opposition leaders, using camera angles that exaggerated support for the opposition movement (which encouraged greater participation), and showing how opposition groups were coming together to launch a joint movement. Similarly, in Algeria, journalists covered the February 2019 protest in ways that helped to encourage mobilization, even disseminating a list of points on how non-violent resistance could be used to overthrow the regime.

In many cases, journalists and newspapers go beyond their traditional role as independent observers to become active players in the opposition. In Algeria, for instance, when the regime tried to crack down on the media and imposed censorship, journalists turned out to protest against the restrictions. (This raises important questions about whether journalists can or should be activists.)

Sanctions and other responses to the Russian invasion of Ukraine are motivated in part by the hope that the consequences—in the case of sanctions, hardship and suffering on the part of Russians and citizens of democracies alike—will help mobilize popular opposition to the war and against Putin’s leadership. But despite protests in Russia against the conflict, the strong repression of anti-war protest will make it dangerous to participate and difficult to gauge the full extent of popular dissatisfaction. If tactics to concentrate large numbers of people in public places is too dangerous, tactics of dispersed dissent—many events in many different places—may be more effective. Coordinating tactics and strategies requires dissemination and outreach. Television is the most important source of news for most Russians, dominated by state-controlled channels, and the authorities have blocked access to the last remaining independent TV stations. Despite this, independent newspapers such as Novata Gazeta continue to report on the consequences of the war in Ukraine in Russia. A popular uprising in Russia to topple Putin will be challenging for many reasons, but these independent sources of news help preserve the possibility of effective opposition under very difficult circumstances.

Martín Macías-Medellín is a PhD student in Political Science at the University of Michigan. Mauricio Rivera is a Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). Kristian Skrede Gleditsch is Regius Professor of Political Science at the University of Essex and a Research Associate at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO).