Guest post by Sebastian Hellmeier

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, people across the world have taken to the streets to show their solidarity with Ukraine and condemn Russian aggression. Ukrainians are protesting against the occupation and in Russia, thousands have been detained for speaking out against the war at dozens of demonstrations across the country.

On March 18, Russian state TV painted a different picture. According to official sources, 200,000 supporters of President Putin gathered in the packed Luzhniki stadium to celebrate the anniversary of Crimea’s annexation. Participants waved Russian flags, sang patriotic songs, and expressed their unconditional support for their leader and the ongoing “special military operation” in Ukraine. In addition to Vladimir Putin, several celebrities and athletes attended the event.

Was the gathering an organic outpouring of support for Putin? Independent journalists quickly revealed that it was not. Participants were bussed in from outside Moscow; they received food or money in exchange for turning out. Those who depend on the government—like public sector employees—were pressured to attend. Every detail of the event was choreographed to make sure that the message of broad-based popular support for Putin came across.

This is not to say that there was no genuine support for Putin at the event. Although surveys from Russia should be taken with a grain of salt these days, recent polls show strong patriotic attitudes among Russians, and Putin has enjoyed high levels of popularity throughout his time in office. The annexation of Crimea further boosted his popularity.

Still, events like the mass rally in Moscow are top-down efforts to signal regime support. More puzzling than Putin’s public appearance at the event is that pro-war mobilization in Russia has been limited so far.

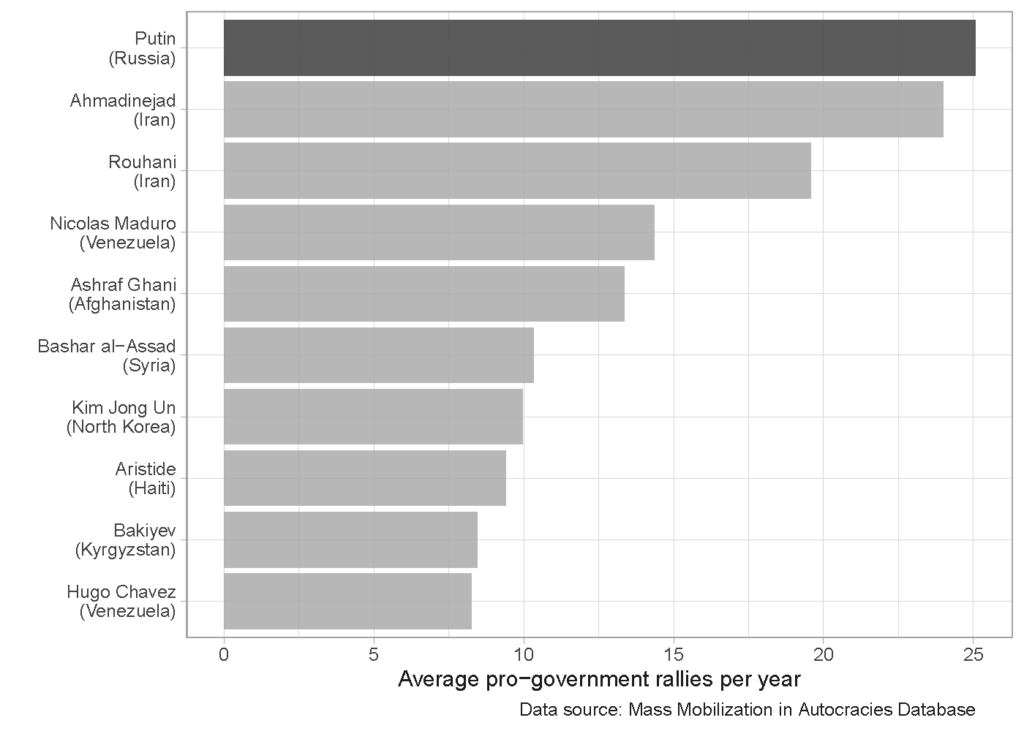

Mass demonstrations in support of incumbent leaders occur regularly in authoritarian regimes. While anti-government protests are typically organized by the opposition, slightly more than ten percent of all events in non-democracies are pro-government, according to the Mass Mobilization Autocracies Database. Figure 1 shows the ten authoritarian leaders that were at least two years in office with the most pro-regime rallies per year during the last 20 years, with Putin at the top of the list. During Putin’s presidency, there have been hundreds of demonstrations supportive of his regime. What makes Russia unique is the lack of any strong ideological foundation to the pro-Putin movement. In dictatorships like Iran and North Korea, mass mobilization becomes a kind of ritual and citizens are encouraged to display enthusiasm for the regime at regular intervals. By contrast, the Kremlin mobilizes the masses by emphasizing negative emotions such as anger and fear without promoting a clear political project.

Autocrats mobilize their supporters to increase the likelihood of staying in power. They can encourage nationalist protests because it helps to signal resolve and improves their bargaining position on the international stage. Domestically, regime supporters can help counter anti-government movements by occupying public spaces, attacking opposition activists, and creating turmoil, giving security forces a pretext to intervene. Moreover, large-scale pro-regime mobilization can deter coup plotters who would need public support if they managed to successfully remove the incumbent leader. In a quantitative study co-authored with Nils Weidmann, we found that pro-government rallies are more likely when the risk of a coup is high and when anti-government protests are unfolding in neighboring countries. We also found that there are generally more demonstrations prior to elections—likely because they signal broad-based regime support for the regime (regardless of election results).

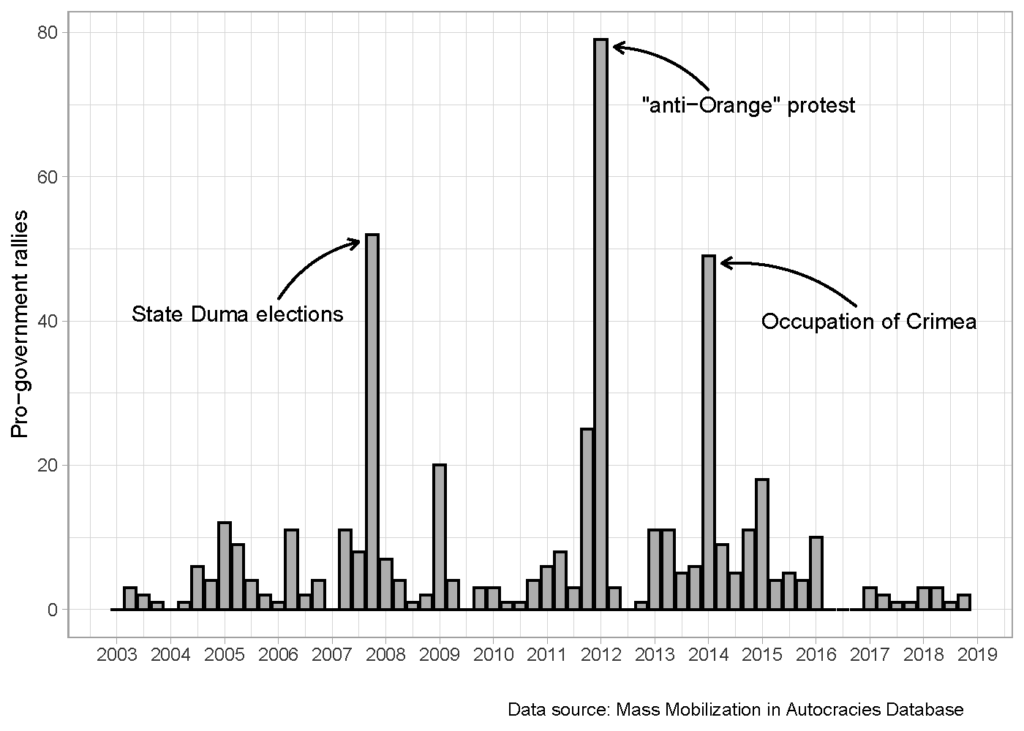

Figure 2 shows the number of pro-regime rallies held during Putin’s time in office. They spiked first around the legislative elections in 2007 to support Dmitry Medvedev’s temporary takeover as president. In 2012, large-scale mobilization was orchestrated to prevent a “color revolution” that washed away dictators in several post-Soviet countries and rallies were aimed at creating an image of invincibility ahead of unfair elections. The annexation of Crimea sparked another wave of pro-Putin rallies in 2014. In a nutshell, Putin did not mobilize the masses when his popularity was already high, but rather when he needed to project strength.

Compared to 2014, there have been few pro-government rallies in Russia since the invasion of Ukraine in February. There are a few reasons why. First, the anti-war movement does not—yet—pose a severe threat to Putin’s rule. Despite hundreds of protests across the country, mass mobilization has not reached critical levels. Prominent opposition figures like Alexei Navalny are in jail and civil society organizations have been repressed for years. Second, the Russian regime can rely on the legal and physical repression of dissent to counter the anti-war movement. Thus far, police and security forces have followed orders to crackdown on protesters. And despite instances of disloyal behavior among individual secret service agents, there have been no major splits within the elites.

Though Putin does not seem to need street support to stay in power at the moment, there are two scenarios that could drive pro-government mobilization soon. If the anti-war movement grows and mobilizes to the degree that security forces are unable or unwilling to repress protests, or if Putin fears a coup plot against him, he might call on his supporters to defend him.

Sebastian Hellmeier is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the research unit “Transformations of Democracy” at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center and a Research Associate at the Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem) in Gothenburg.