Guest post by William G. Nomikos

In a recent New York Times op-ed entitled “I Love the U.N., but It Is Failing,” Anthony Banbury, a former top UN official, argues that UN peacekeeping does not accomplish its most important goals. The graphic above the body of the text features the trademark UN flag’s olive branches enveloping a black hole rather than the usual world map. The suggestion is clear: UN peacekeeping operations are international quagmires with minimal or no positive impact. Scholars have echoed this sentiment, and maintained that the UN fails to adequately consult local actors, and relies instead on cookie-cutter approaches that emphasize international best practices over domestic political realities. Some have even suggested that UN peacekeeping operations may unintentionally drag violent conflicts out by empowering corrupt, war-mongering elites. Séverine Autesserre puts it even more bluntly: “the UN can’t end wars.”

Such pessimism is unwarranted. Critics underestimate the effectiveness of UN peacekeeping operations because they overlook peacekeepers’ ability to enforce nonviolent solutions to communal disputes. Civilians usually choose to cooperate to peacefully resolve a dispute when doing so is more beneficial—or less costly—than violent dispute resolution, which is often not the case in conflict settings. Locally deployed peacekeeping patrols can increase civilians’ willingness to cooperate with members of other groups by lowering the perceived risks and dangers associated with cooperation.

UN peacekeepers are uniquely able to limit the escalation of communal disputes because local populations perceive them as relatively impartial. The UN is a multilateral international organization branded as a peacemaker. Indeed, it is an especially diverse international organization with 193 sovereign member states. Unlike former colonial powers or neighboring countries with similar ethnic cleavages, domestic populations do not associate the UN with the interests of specific ethnic, religious, or tribal groups. In addition, the UN’s rules of engagement proscribe violence against civilians. These constraints on its operations enhance the UN’s reputation for impartiality because when international actors commit violence against individuals from a certain group, other members of that group believe the actor is systematically biased against them.

To better understand how UN peacekeepers are perceived, I carried out an experiment in Mali, a West African country with ongoing communal conflicts managed by troops from the UN and France. The mandate, size, and budget of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) as well as the challenges faced by peacekeepers there are emblematic of UN peacekeeping in the modern era. For example, UN peacekeepers have become heavily involved in local-level peace processes in the Central African Republic.

The evidence shows that UN peacekeeping had a strong positive effect on people’s willingness to cooperate, whereas French peacekeeping had no substantive or statistically significant effect. Why did Malians prefer the UN? One 22-year-old male participant said he preferred the UN to France because “it did not colonize Mali and therefore will not target any interests.” Others referenced the multinational nature of UN peacekeeping operations as a consideration. Another 22-year-old man said that he preferred the UN “because it’s an international institution specifically created to maintain peace.”

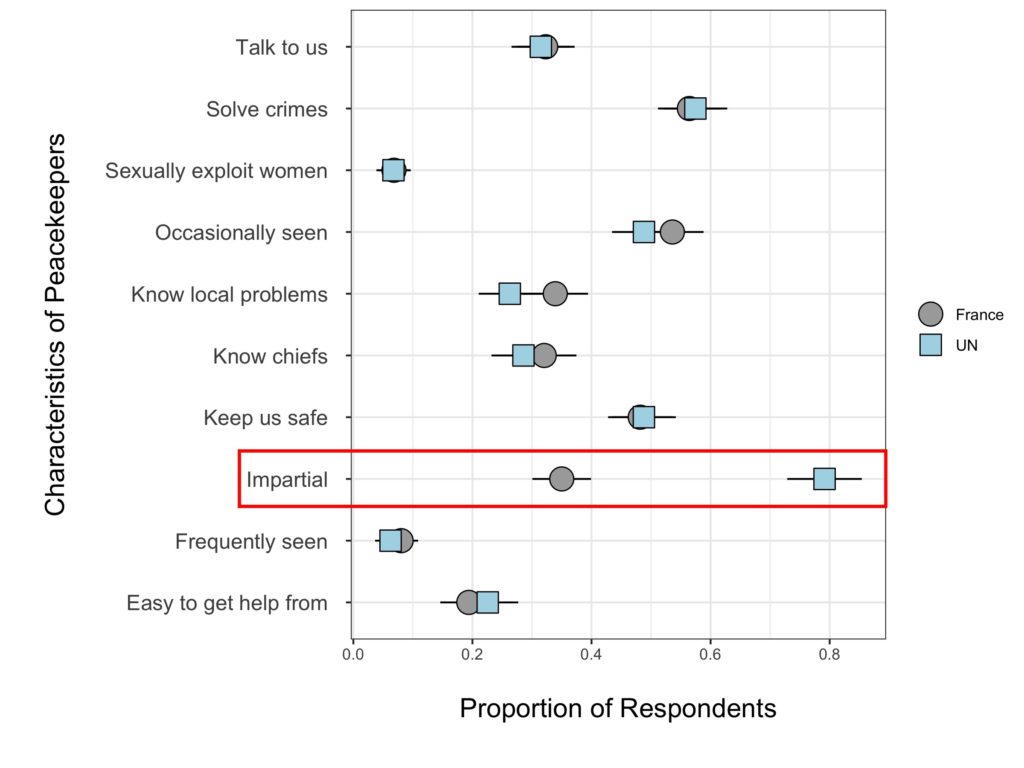

Perceptions of the UN as impartial likely drive these divergent findings. I conducted a follow-up survey with 874 Malians living in 20 rural and peri-urban areas to understand the characteristics of UN peacekeepers and French soldiers. The results suggest that the belief that UN peacekeepers do not favor certain ethnic groups drives their perceived effectiveness. Whereas nearly 80 percent of all respondents think of UN peacekeepers as impartial, fewer than 40 percent say the same about French soldiers (see highlighted box in Figure 1).

Not all reported perceptions were positive. Sexual exploitation by UN peacekeepers was mentioned by 7 percent of respondents, who said women in their village had been victims. The actual number may be even higher. In a recent survey conducted in Liberia, more than 75 percent of all women surveyed had had some form of transactional sex with peacekeepers. These numbers are highly concerning and suggest important limits to the UN’s effectiveness. Given how important perceptions are, allegations of sexual exploitation are a pressing operational as well as normative concern.

Although UN peacekeepers increase interethnic cooperation at the local level, it remains an open question whether that cooperation leads to long-lasting peace. In a related study, I found that the UN decreases communal violence and violence between armed groups but has more limited effects on rebel violence against civilians. In fact, the presence of the UN may increase government violence against civilians.

Ultimately, local communities must use the gains from cooperation to create domestic institutions that can sustain peace even after the peacekeepers have gone. Research from successfully concluded UN peacekeeping operations in Cote d’Ivoire and Liberia suggests that the UN can help here as well. Peacekeepers mitigate electoral violence, catalyze state reform by writing legislation, and promote the rule of law. As a result, cross-national studies have found that UN peacekeeping operations not only reduce violent conflict but also help build lasting democratic institutions in post-conflict settings.

William G. Nomikos is an assistant professor of political science at Washington University in St. Louis.