Guest post by Yu-Ping Chang and Ghashia Kiyani

The death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who died in custody after being detained for improperly wearing a hijab, ignited protests across Iran. Though the Iranian government blames foreign influence, the demonstrations are more diverse than any in Iran’s recent history. They include students, merchants, artists, athletes, business owners, and a range of ethnicities. Moreover, women have been at the forefront, demanding women’s rights, while taking off headscarves and cutting their hair.

What influence, if any, will these protests have on women’s rights in Iran, and on the shrinking space for the civil society organizations that advocate for them?

This year’s protests are part of a larger trend of demonstrations and civil activism that have been ongoing in Iran since 2016. They have occurred against a backdrop of US sanctions, rising inflation, low wages, poor working conditions, and significant unemployment. In 2021, economic hardship was further compounded by water shortages and electricity blackouts due to unusually high temperatures.

Suffice to say, the Iranian government is facing economic and political vulnerabilities. And like many states, the government is relying on its coercive apparatus to crack down on an increasingly agitated and mobilized population. Civil society leaders have been a particular target.

Much of the Iranian government’s power comes from the loyalty of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which itself depends on the government’s support to consolidate its economic interests. This arrangement is common among countries in the Middle East where militaries engage in profitable business—ranging from automotive, iron and steel, agrochemicals, construction, banking, tourism, and petroleum distribution—to supplement their state budgets. IRGC’s economic dependence on the government, plus its ideological alignment with the values of the Islamic Republic, means that it is likely to continue to do the government’s bidding and inflict violence on protesters.

Once the protests subside, the government’s violent crackdowns may ebb, but repression is likely to continue. Research on civil society suggests that the government will further narrow civil society spaces through laws and regulations, administrative impediments, and harassment of activists and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Administrative measures—including erecting high thresholds for the registration of NGOs and human rights organizations and limiting access to financial resources—are likely to be adopted to curtail the activities of advocates, labor unions, and other civil society groups.

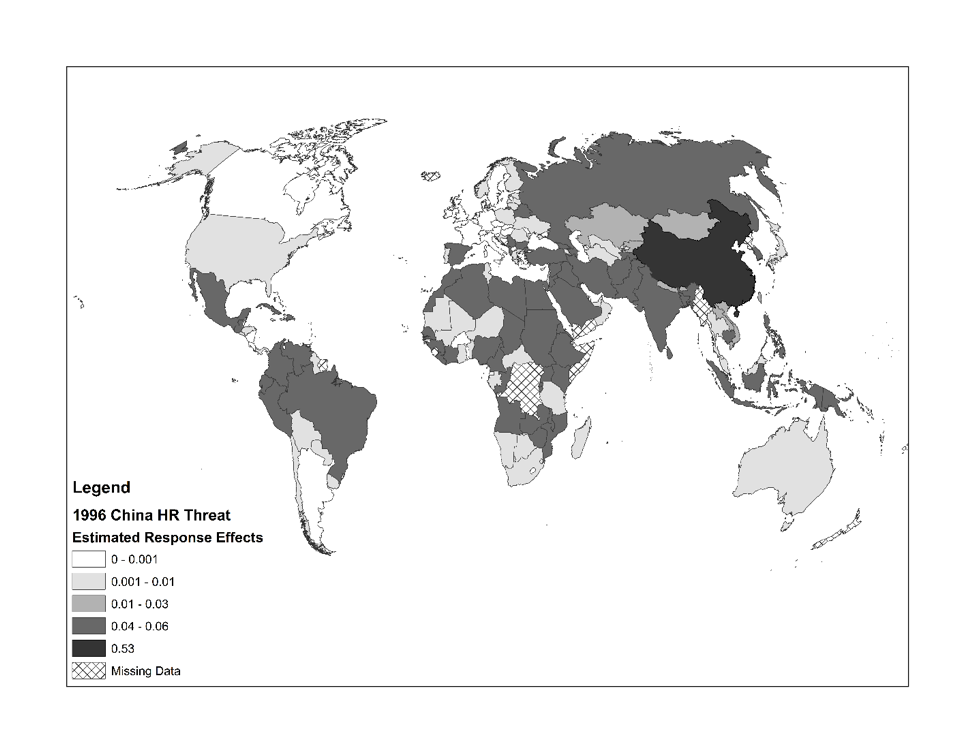

To prevent a further shrinking of civil spaces and violations of human rights, activists should focus on a strategy of naming and shaming—identifying human rights violators to a broader international audience—coupled with strong advocacy within the NGO networks. Iranian women’s NGOs need to cooperate with one another and form connections with the international community of human rights organizations. Transnational networks provide allies, including state actors and other international advocacy groups, that can exert pressure on repressive regimes. With domestic NGOs and the international community exerting pressures from the bottom up and top down, regimes are more likely to suffer reputationally and make concessions. One such example is Argentina in 1976 where police engaged in physical torture and women experienced increased violence. Domestic and international NGOs like Amnesty International named and shamed the Argentinean government for its rights abuses. In response, foreign governments like France, Sweden, and the US condemned rights violations, and the US reduced military aid to Argentina. As a result, Argentina’s government took concrete measures to address human rights violations.

The naming and shaming strategy should avoid playing into the Iranian government’s strategy of convincing Iranians that protests are being instigated by outside actors. In promoting women’s rights, NGOs and civic groups should formulate narratives that have the potential to win over friends, or at least not to create more antagonism between citizens and the government and more alienation among the population that fears foreign influence.

Advocates must similarly calibrate their advocacy to increase the likelihood that the Iranian government will make concessions on women’s political rights. Studies of women’s NGOs in Iran show that when civil society groups avoid seeking changes in laws—which could call into question the legitimacy of the regime—and instead focus on changing social attitudes, creating spaces for dialogue and debates, and developing programs that improve individuals’ lives, the government loosens restrictions on these groups. Advocates may also want to focus on less divisive issues that are nonetheless vital for women’s empowerment, such as labor force participation. Although Iran’s unemployment rate has ranged between about 10 to 13.7 percent overall over the past decade, the rates are consistently higher for women, at between 17 to 21.1 percent. More advocacy is needed to improve women’s economic and social rights in Iran.

So, how likely are these protests to produce change for Iranian women? At the moment, women’s rights groups in Iran, and individual women involved in the protests, face the long-term prospect of continuous repression. Nevertheless, discontent among the population is unlikely to die out soon given that these grievances are widespread and rooted in structural factors that cannot be addressed overnight. Academic research shows that protests that cut across demographic groups are more likely to achieve change. Iranian advocacy groups thus have the opportunity to take advantage of this momentum to sustain their efforts to keep pressure on the government from below, while aided by the international community of human rights advocates.

Yu-Ping Chang holds a doctoral degree in Security Studies from Kansas State University. Ghashia Kiyani is a Donald R. Beall Defense Fellow at the Naval Postgraduate School and a Visiting Assistant Professor at Western Illinois University.