Guest post by Gustavo Flores-Macías and Jessica Zarkin

This post is part of a series on illicit economies, organized crime, and extra-legal actors and came out of an IGCC-sponsored conference hosted in October 2022 by the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at UC San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy.

In today’s world of seemingly endless examples of police misconduct, brutality, and ineffectiveness worldwide, many wonder whether the armed forces can do a better job at providing public safety. Resorting to the military can seem like an especially appealing policy alternative in contexts where the civilian police appear overrun by criminal organizations, as is currently being debated in Argentina.

This is why we often hear calls to deploy US troops to address drug cartel violence in Mexico, or why many governments around the world rely heavily on the armed forces to fight organized crime, as in Honduras, Ecuador, Indonesia, or the Philippines. The logic is that militaries tend to be better trained, better equipped, and more disciplined than police. Because of these features, militaries are thought to be less prone to become corrupted into helping criminals, better at catching them and deterring crime, and better at respecting civil liberties while doing so.

Is there merit to the militarization of policing?

A growing body of evidence suggests that the answer is negative. In particular, the militarization of law enforcement is increasingly associated with higher levels of violence without a corresponding decrease in crime. This finding applies to both the developed and developing world. It also holds in contexts where police are becoming more like militaries and in contexts where the military themselves have been constabularized for domestic policing.

However, less evidence exists around the question of whether involving the military in policing also has consequences for human rights violations. Answering this question is often difficult because of the challenges involved in systematically evaluating performance. On the one hand, perceptions of performance do not necessarily match reality. For example, in spite of the evidence that militaries do not perform better than civilian police at reducing crime in democratic contexts, perceptions can suggest otherwise in contexts where the military enjoys high levels of society’s trust.

On the other, even if we can agree on the right objective measures of performance, reliable data are often difficult to come by, and the non-random assignment of the military to policing tasks complicates analysis. Militaries are often deployed to the most dangerous areas and into the most challenging environments—those in which respecting civil liberties may be especially difficult for both police and military.

Just as supporters of militarization point to the reasons why militaries may be more effective at respecting human rights—including superior training and discipline—detractors suggest that inherent features of the armed forces can also lead to greater violations. For example, military training does not typically revolve around defusing conflict situations but emphasizes survival and destructive capacity. Even if militaries receive human rights training, soldiers’ mindsets remain focused on defeating an enemy, and soldiers can easily fall back on military understandings when facing challenging policing situations. In highly discretionary contexts typical in policing, judgments about the appropriate levels of force can be elusive.

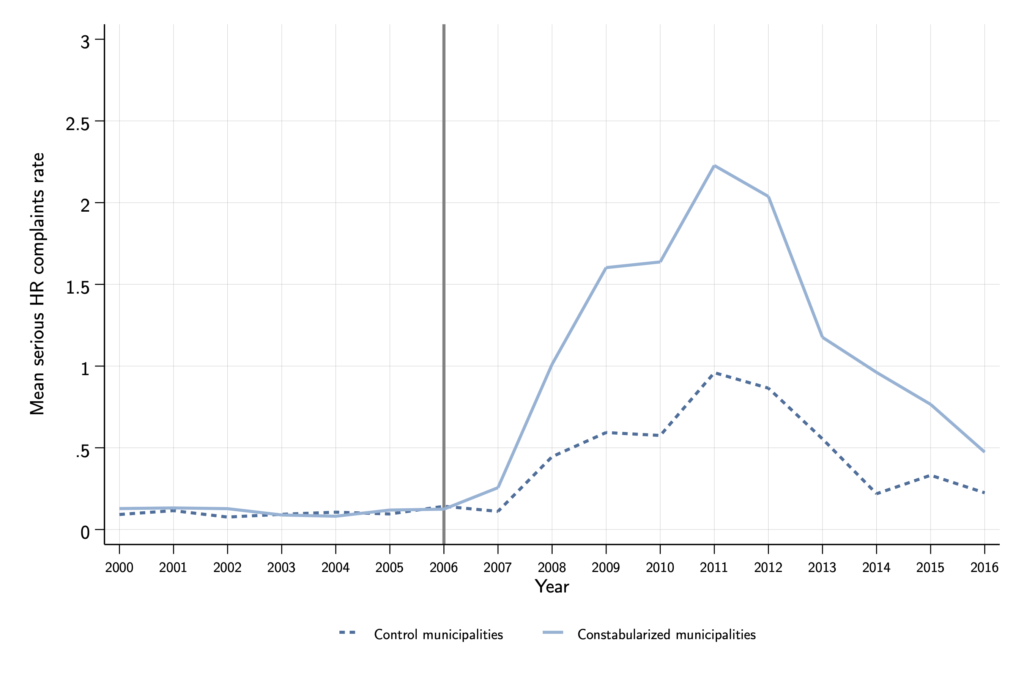

To shed light on the merits and risks of militarized policing, we looked at military deployments for policing in Mexico beginning in 2006. Based on disaggregated data on military deployments and human rights abuses, which were obtained through numerous right-to-information requests, we compared municipalities with military operations with similar municipalities without military deployments.

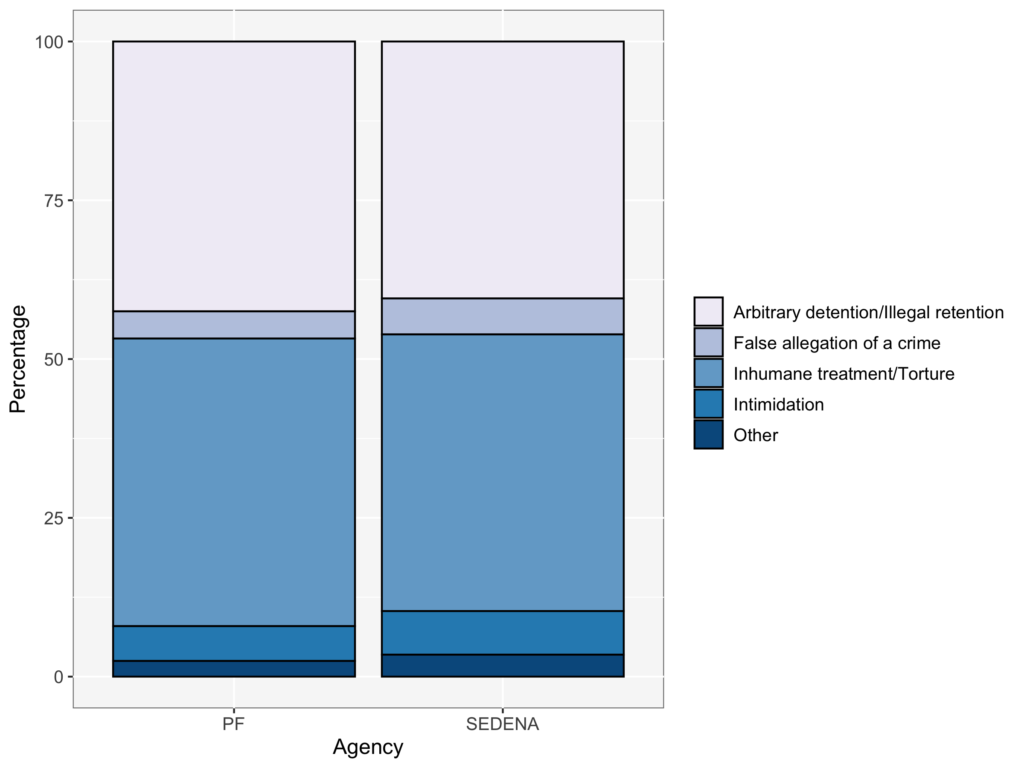

What we found was not encouraging. First, we found that the prevalence of different types of human rights abuses filed before Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) against the military was similar to those filed against civilian federal forces between 2000 and 2016. Both agencies engaged primarily in abuses related to inhumane treatment and torture, accounting for about 45 percent of the total for each agency.

We also found that the rate of serious human rights abuse complaints against security forces was higher in municipalities where military operations took place. In particular, rates per 100,000 people were between 150 percent and 218 percent higher than in comparable municipalities without military deployments between 2006 and 2016.

Importantly, the increase in abuse complaints cannot be explained by features inherent to the armed forces (e.g., they are more trustworthy) or underlying characteristics (e.g., a more active civil society) of the municipalities that had military operations. Instead, we found that the increase in complaints was a product of the military’s participation in policing.

Although these findings speak to the case of Mexico and may not necessarily apply in all contexts, they are consistent with the mounting body of evidence pointing to the negative consequences of the militarization of law enforcement. They also reinforce the view that even though specific policing tasks may warrant using the armed forces, police reform should be a high priority for governments facing violent crime. This requires investment in capacity building and career development, as well as strengthening managerial processes in order to generate procedurally just and productive interactions with citizens.

Gustavo Flores-Macías is associate vice provost for international affairs and professor of government and public policy at Cornell University. Jessica Zarkin is assistant professor at Claremont McKenna College.