Guest post by Mark Joslyn and Don Haider-Markel.

When House Majority Whip Steve Scalise was shot and severely wounded in Alexandria, Virginia, it marked the second attempted assassination of a congressional representative in six years. In 2011, Arizona Representative Gabrielle Giffords survived an attempt on her life in Tucson that killed 6 people and injured 13 others.

In the wake of both tragedies, elected officials and news media focused on the harsh political imagery and rhetoric preceding the shootings. In 2011, Democrats pointed to Conservative rhetoric, in particular the Tea Party and Sarah Palin’s PAC that featured stylized crosshairs targeting Gifford in the 2010 midterm elections.

After Virginia, Republican critics cited examples of progressive political discourse that crossed the line of civility, especially since the Trump victory, including the controversial production of Caesar in Central Park.

The two shootings thus offer a comparison of people’s beliefs about a connection between political language and violence. Do people believe political language was an important factor that influenced the Arizona and Virginia assailants? Do beliefs change depending on the party identification of targeted elected officials?

A multitude of academic studies examine the highly partisan climate characteristic of our politics today. Many citizens now see this climate as a prime cause of violence against elected officials.

The climate of politics – a substantial percentage of Democrats see a connection between political language and violence.

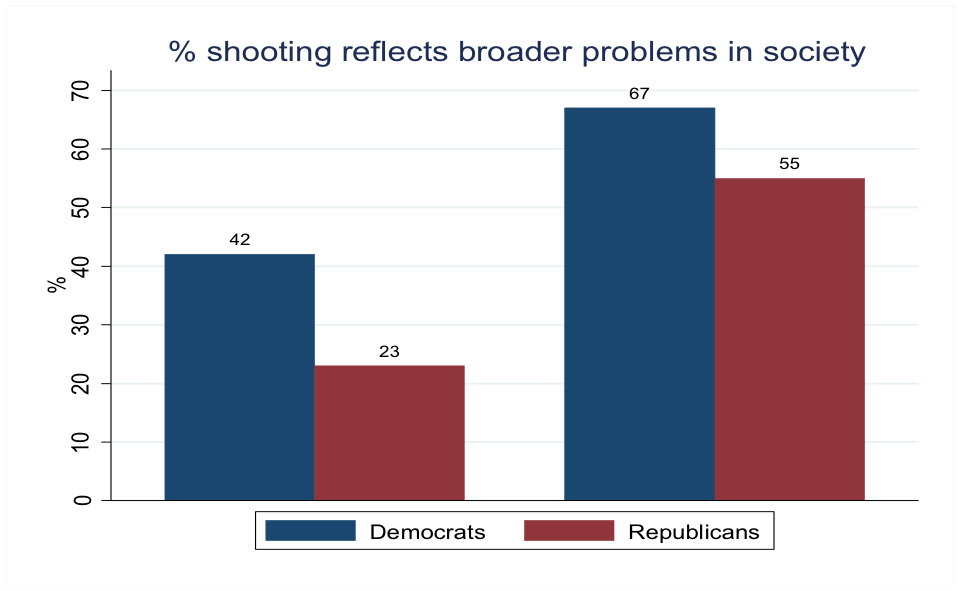

Angry, divisive words, rants, and political incivility breed extreme attitudes and set the stage for the deranged and alienated to lash out – an individual gunman’s malicious behavior is then a predictable result of the larger political environment. Democrats generally ascribe to this view. For every high profile mass shooting since Virginia Tech, Democrats were more likely than Republicans to believe shootings reflected broader problems in society, as opposed to isolated acts of troubled individuals. Typically Republicans blame the individual and do not connect shootings to systemic problems.

This partisan pattern developed quickly after the Arizona shooting. Just one day after the attack, CBS News asked people whether the harsh political tone of recent political campaigns had encouraged violence and influenced the Arizona shootings. Among Democrats, 57% saw a connection between harsh rhetoric and the shootings while only 24% of Republicans did so.

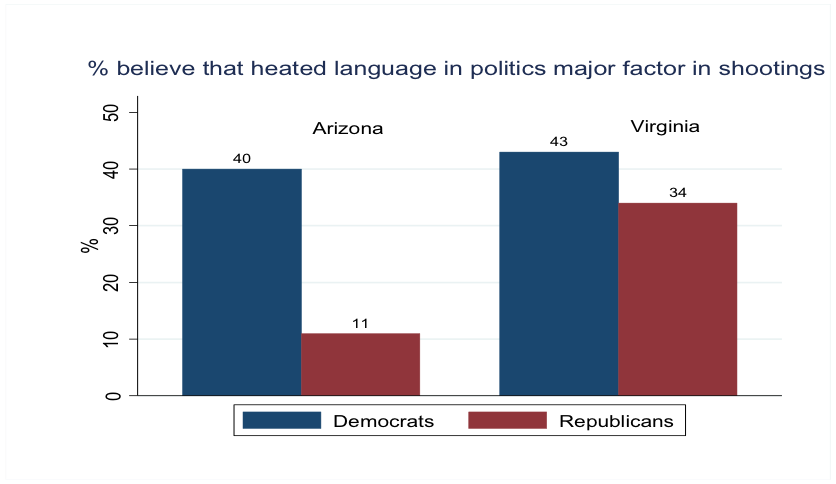

Gallup asked a similar question: “Do you think the heated language used in politics today was or was not a factor influencing the Arizona shooter to commit the attack?” Forty percent of Democrats but only 11% of Republicans thought rhetoric was a major factor.

Alexandria Virginia shooting was different – Republicans see a connection between harsh rhetoric and violence.

Since it was harsh language and imagery of Progressives at issue after the Virginia shooting, we expected more Republicans to identify heated language as an important factor. Two weeks after Alexandria, our research team fielded a poll asking the identical Gallup question except to reference the “Virginia” shooter. The percentage of Democrats that thought heated language was a major factor was about the same as after Arizona – 43% but the percentage of Republicans increased notably to 34%.

A recent Rasmussen analysis of the two shootings showed a similar yet even stronger pattern. Thirty-seven percent of Democrats and 20% of Republicans attributed the Arizona shooting to political anger; however, the percentages reversed, and sharply increased, after Virginia. Sixty-eight percent of Republicans and 49% of Democrats cited political anger as the cause.

The data suggest a greater number of Republicans were motivated to identify political language as a significant factor when the target of violence was a Republican leader. This is an important change in causal attributions and appears connected to perceiving shootings as reflecting larger social and political forces.

For example, a majority of Republicans considered the Virginia shooting a reflection of broader problems in society – this is a considerable increase over Arizona. While Democrats ‘broader problem’ attribution rose as well, the attribution gap between the parties was much smaller after Alexandria.

We cannot predict how long this relative accord may last. The data across the last several high profile mass shootings – Newtown, Orlando, and Alexandria — does show similar percentages of Democrats and Republicans attributing shootings to broader forces in society.

Our analyses of Alexandria and other mass shootings consistently show that the ‘broader forces’ attribution is a key predictor of support for stricter gun control laws. On the other hand, perceiving the cause of violent shootings as the act of troubled individuals favors status quo.

Sixty three percent of people that believed the Alexandria shooting was the act of a troubled individual said their opinion about gun control was not changed by the shooting. However, among those attributing the shooting to broader problems, 33% said the tragedy made it more likely they would support stricter gun control measures. Only 19% of those attributing the shooting to a troubled individual said they would support stricter gun laws. Democrats and Republicans follow this same pattern in this regard. And, in the Alexandria case, more Republicans attributed the shooting to broader forces than in past shootings.

In this respect, if mass shootings are perceived as motivated by political anger and vitriol, and the target of violence is a Republican political figure, it may well produce the attitudinal antecedents of stricter gun control policies.

Mark Joslyn is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Kansas. Don Haider-Markel is a Professor of Political Science at the University of Kansas.

2 comments

You don’t think 6 years of PC and leftist riots changed anything? A rookie mistake with statistics is to ignore trends of external factors over time.