Guest post by Corey Ray and Sofia Smith.

The disappearance and assumed murder of activist Jamal Khashoggi by the Saudi government, allegedly on Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman’s (MBS’s) orders, has enraged even some of his staunchest supporters. Though unique in its brutality and boldness, Khashoggi’s case does not surprise those who follow Saudi Arabia’s long history of disappearing journalists, jailing activists, and torturing dissidents. But targeting Khashoggi, who had been living in self-imposed exile in the US and writing columns for the Washington Post, has apparently touched a particular nerve. Calls for the US to curb weapons sales to Saudi Arabia have grown more widespread in the days following Khashoggi’s October 2 disappearance in Istanbul. Yet to effectively pressure MBS and his supporters, human rights advocates’ need to leverage the business ties that support the regime.

Shaming the Shameless?

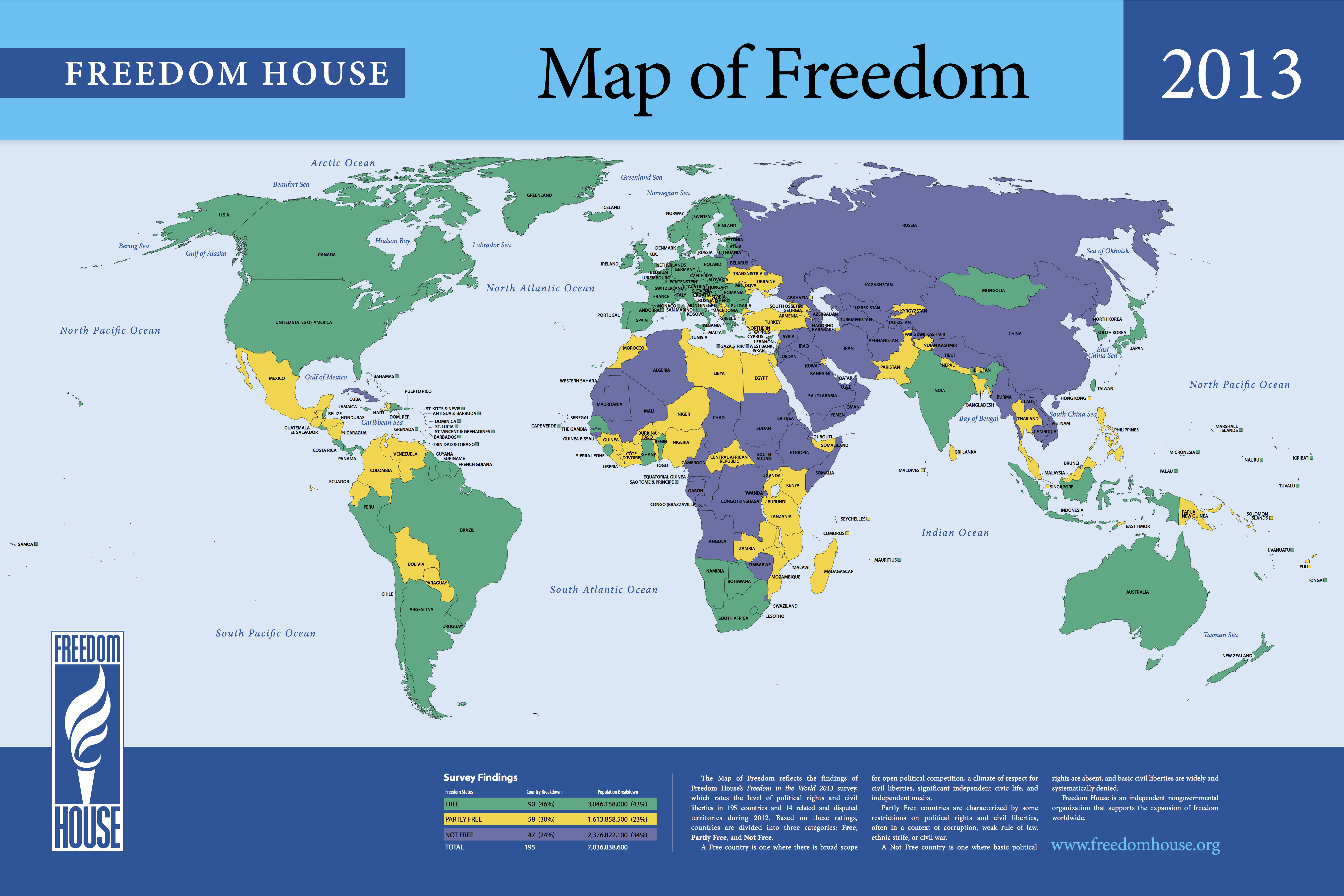

Whether it was the widespread incarceration of senior princes and billionaires, the continuing arrest of women’s rights activists, the repression of religious minorities, or the silencing of journalists, the Saudi regime has a troubling human rights history that has only gotten darker with MBS’s ascension. The case of Raif Badawi, a liberal blogger sentenced to 10 years in prison and 1,000 lashes, recently caused public outcry and a diplomatic spat with Canada. Despite more than six years of pressure from activists, NGOs, and the governments of Canada, Germany, and Sweden, Badwai remains imprisoned and in ill health. Badawi’s plight, along with those of figures such as women’s rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul, illustrates the seeming futility of crusading for human rights in a country seemingly impervious to criticism because of its economic and strategic importance.

Research on “naming and shaming” demonstrates that this happens all too often. Human right violators rarely change their behavior after shaming, particularly in consolidated autocratic regimes such as Saudi Arabia. Rare, successful shaming approaches often employ the “spiral model,” with international actors working closely with local non-governmental organizations or advocacy groups to combine bottom-up and top-down pressure. These actors’ combined strength and organization often make the difference between successful reform or harsher crackdown. Yet with many of Saudi Arabia’s activists and dissidents already in jail—and those who are “free” under immense pressure—finding local partners for this sort of effort can prove challenging.

That said, even authoritarian regimes care about the bottom dollar (or, in this case, riyal). Evidence shows that states that have improved their human rights behavior often did so when a threat to aid or foreign direct investment accompanied shaming. In this light, American activists such as Shaun King may have the right idea. On October 11th, King called out celebrities, tech figures, and politicians for their relationships with MBS, tagging individuals in personalized Tweets while urging them to help secure justice for Jamal Khashoggi. Indeed, targeting Silicon Valley and media outlets has already demonstrated tangible outcomes. Why is this important?

Much of the initial optimism toward MBS came from his plan to transform the Kingdom into an Arabian Silicon Valley via a plan dubbed “Vision 2030.” A McKinsey & Company report that inspired Vision 2030 highlights critical domestic challenges that, left unsolved, call into question the regime’s long-term durability. It argued that booming population growth and dismal prospects for long-term oil revenue present an existential threat to the regime. It also noted that even if the Saudis replaced all migrant foreign workers with local labor (an unlikely scenario), the unemployment rate could still exceed 20%. Real average household incomes for Saudi citizens are set to fall by about 20% by 2030. Without structural economic transformation, massive government deficits will fuel an unsustainable debt burden.

These dire predictions, coupled with research on regime concessions, highlight the regime’s vulnerability to economic pressure for the first time since the discovery of oil. Despite the high hopes afforded to Vision 2030, the plan is off to a rocky start. In August, MBS indefinitely delayed the initial public offering (IPO) for ARAMCO, the state-owned oil company, calling into question Vision 2030’s core source of funding. Without the billions of Saudi riyals from the IPO, the regime must rely even more heavily on foreign investors.

Additionally, investors have been wary following MBS’s shakedown of prominent (if likely corrupt) domestic investors such as Prince Alwaleed bin Talal. As recently as last weekend, Saudi officials provoked even further market concern by launching a veiled threat to undermine global economic growth via oil markets in retaliation for sanctions in the Khashoggi case. But with severe capital flight already underway, Saudi markets cannot afford to lose major foreign investors.

While generic “naming and shaming” of foreign firms working in Saudi Arabia is likely to fail, focusing on high-visibility corporations directly connected to Vision 2030’s success could gain traction. The types of image-conscious firms involved in Vision 2030—such as Google and Apple—offer hope for the potential success of these techniques. Only recently, a naming and shaming campaign compelled Amazon to raise workers’ wages. MBS courted Amazon in particular to build cloud computing and data services for the kingdom. Google, Apple, and Snap also have specific roles to play in developing Vision 2030. As of October 17th, MBS’s signature conference, the Saudi Future Investment Initiative, seems to be in real trouble. Major tech and media sponsors and participants including Richard Branson, Uber, Siegy, Viacom, Virgin Hyperloop, The Huffington Post, The New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times have all withdrawn. Without their investment and public support, the Saudi economy risks serious instability under rising unemployment, increasingly burdensome public debt levels, and collapsing standards of living.

A New Hope

Convincing companies to take concrete actions focuses on the regime’s biggest pressure point: economics. The regime’s persistent backtracking on economic reform and reliance on the Vision 2030 lifeline exposes vulnerabilities that activists can leverage. Energy companies and the US government may not be moved, but big tech has branded itself as modern and socially conscious. To paraphrase Adam Smith, it is not from the benevolence of Google, Facebook, or Amazon that activists can expect action, but from the regard for their own self-interest.

Sofia Smith is a Master’s candidate in International Economics concentrating on the Middle East at Johns Hopkins SAIS. Corey Ray is a Masters candidate in International Economics and Middle East Studies at Johns Hopkins SAIS.