Guest post by Daniel Karell and Sebastian Schutte.

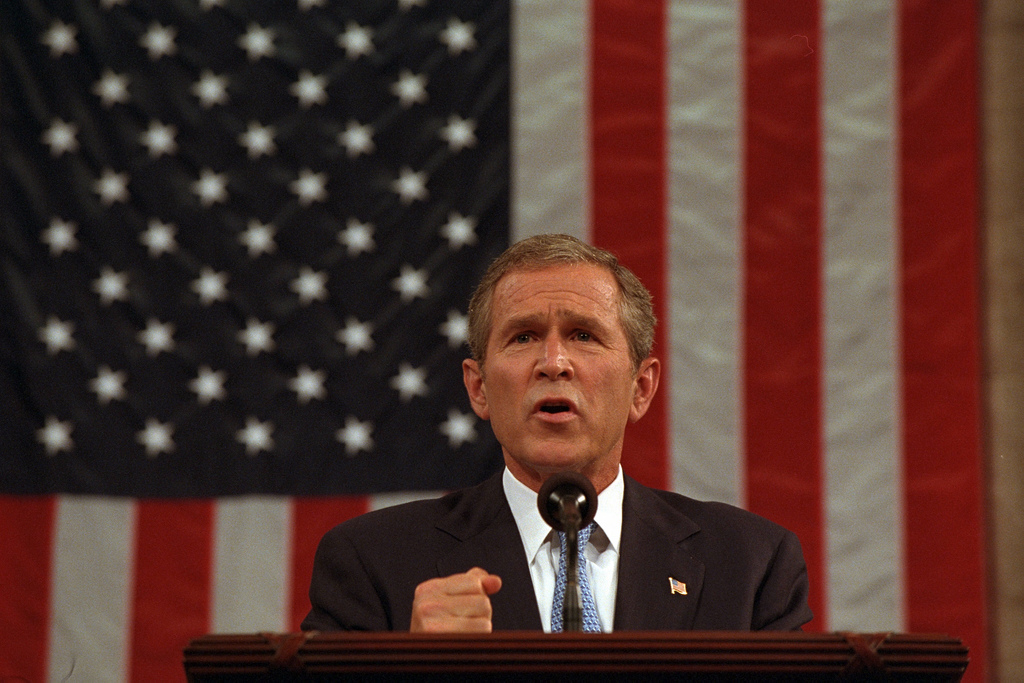

Can military forces mitigate insurgent activity—“win hearts and minds”—by implementing small, localized aid projects? Evidence from the recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq has provided contradictory answers to the question of aid’s ability to mitigate violence. Some research finds that aid projects increase the legitimacy of the state among civilians and, under specific circumstances, dampen violence. Other studies, however, show that aid projects provoke insurgent activity, even when delivered by non-military organizations.

Despite this ambiguous understanding of counterinsurgency (COIN) aid projects, the US military and its allies spent billions of dollars in Afghanistan and Iraq on projects meant to “win hearts and minds’’ among the populace. After all, there are good theoretical reasons for doing so. Aid projects might make the option of taking up arms less attractive by offering employment opportunities and stimulating local economies (i.e., the “opportunity cost” model of participation in rebellion). They might also encourage locals to share vital anti-insurgent intelligence with military forces.

A common assumption runs throughout these studies: the dynamics that influence COIN outcomes occur among, first, incumbent militaries and civilians and, second, insurgent groups and their potential recruits. We argue that a key piece of the puzzle is missing. Namely, what happens within local communities. That is, aid projects can influence pre-existing intra-community dynamics in ways that subsequently shape insurgencies. Building on this intuition, we recently investigated how aid projects affect insurgent activity in Afghanistan via their impact on social dynamics within local communities. We find evidence that specific kinds of US military aid projects increased violence because of how they created inclusion and exclusion at the community-level.

Aid, exclusion, and violence

First-hand accounts from practitioners, (ex-)soldiers, reporters, and researchers in Afghanistan and Iraq shed light on how residents of unstable, precarious communities often interpret the distribution of resources through the lens of a localized “zero-sum game”. In other words, when there are resources to be had—as in the case of COIN aid projects—there are often locally perceived winners and losers. As a result, when externally provided aid projects potentially accrue benefits to only some segments of a community, residents might interpret this as exclusionary.

Exclusion matters because it can engender localized tension and, ultimately, violence. This process—frustration from the perception of inequity resulting in violence—has been long recognized by social scientists (for a review, see the 2011 edition of Ted Gurr’s classic Why Men Rebel), and is commonly known as the “grievance” explanation for conflict.

By drawing together lessons from the field with these social scientific insights, we reason that residents of Afghan communities who perceive themselves as denied the benefits of incumbents’ development efforts would be more likely to support insurgents, thereby increasing incidents of insurgent activity. If we were correct, then, by extension, we should observe aid projects that exclude parts of a community causing an increase in insurgent activity in near proximity to the project.

The empirical study

We tested our hypothesis by conducting a quasi-experimental analysis of local-level aid projects funded by the US military’s Commander’s Emergency Response program (CERP) and insurgent activity between 2004 and 2009. Specifically, we compared the rate of insurgent activity following inclusive and exclusive projects using a Matched Wake Analysis (MWA), a method developed by Sebastian and Karsten Donnay. Inclusive projects, those with the CERP designation of “infrastructure and natural resources projects”, comprised activities such as the building and maintenance of roads and the development of electrical and telecommunications grids. Comparatively exclusive projects, “social protection” CERP projects, provided targeted assistance to marginalized segments of communities by delivering cash or material to individuals deemed vulnerable, either directly or through local contractors and nongovernmental organizations. It is important to note that our argument and analysis posit the effects of any exclusion—inequity in the benefits of aid projects—rather than the specific exclusion of marginalized residents from the gains of wealthy neighbors. Our dataset included 1,482 infrastructure projects, 1,142 social protection projects, and 45,717 incidents of insurgent activity during the period under study.

Our analysis shows that the implementation of relatively exclusive CERP projects causes an increase in subsequent localized insurgent activity—within two kilometers—compared to the implementation of more inclusive infrastructure projects. Moreover, within this two-kilometer window, the positive effect lasts from two days, the smallest temporal resolution we measure, to 20 days, the longest resolution in our analysis. The exact size of the effect varies over this period but, in general, our results indicate that—within two kilometers of a project—one out of five social protection projects causes an incident of insurgent activity, compared to infrastructure projects.

The consistent, localized effects—exactly what we would expect to find if a project is influencing intra-community social dynamics—leads us to an actionable insight: if US military aid projects empower, enrich, or benefit a specific and limited segment of a local population, even if the beneficiaries are marginalized residents, then we should expect greater subsequent insurgent activity.

Implications & conclusion

We conclude by highlighting two implications of our study. First, much more research needs to be done on how third-parties—for example, international aid organizations, COIN operations, and military-civilian development units (e.g., the U.S. Provincial Reconstruction Teams, or PRTs, that operated in Afghanistan and Iraq)—affect communities’ pre-existing socio-political dynamics. For example, it remains unclear whether different kinds of aid programs, such as those implementing small, quick aid projects (CERP) and others that require the building of specific local institutions before aid is disbursed (Afghanistan’s National Solidarity Program), affect localities in different ways.

Second, despite these known unknowns, we show that social, political, and economic exclusion heightens the possibility of social tension and, sometimes, violence. US military aid can backfire when it benefits some residents of a war-torn community over others. Considering that our findings align with a growing body of social science scholarship recognizing the negative impact of social exclusion, policy and military planners should take careful stock of how their activities might unintentionally create exclusion within communities or deepen those same communities’ existing social divisions.

Daniel Karell is an assistant professor of sociology at New York University Abu Dhabi. Sebastian Schutte is a senior researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo and focuses on conflict processes in civil wars.

1 comment

20 years ago Mary anderson published “Do No Harm: How Aid Can Support Peace – or War.” (Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder/London, 1999, 160 pages, ISBN 1555878342), which led to a great discussion within the aid-sphere over negative impacts of aid. I wonder whether this discussion has ever reached out into the sphere of military-driven-aid / COIN?

In my experience, military-driven aid projects are heavily under-evaluted and lack the necessary impact-assessment. They are driven by wishful thinking and are to inexpensive to be seriously monitored. (the whole “huge” Afghanistan aid programme of the German Army in 2007 was about 1% of the overall budget for the Afghanistan mission)

sigh…